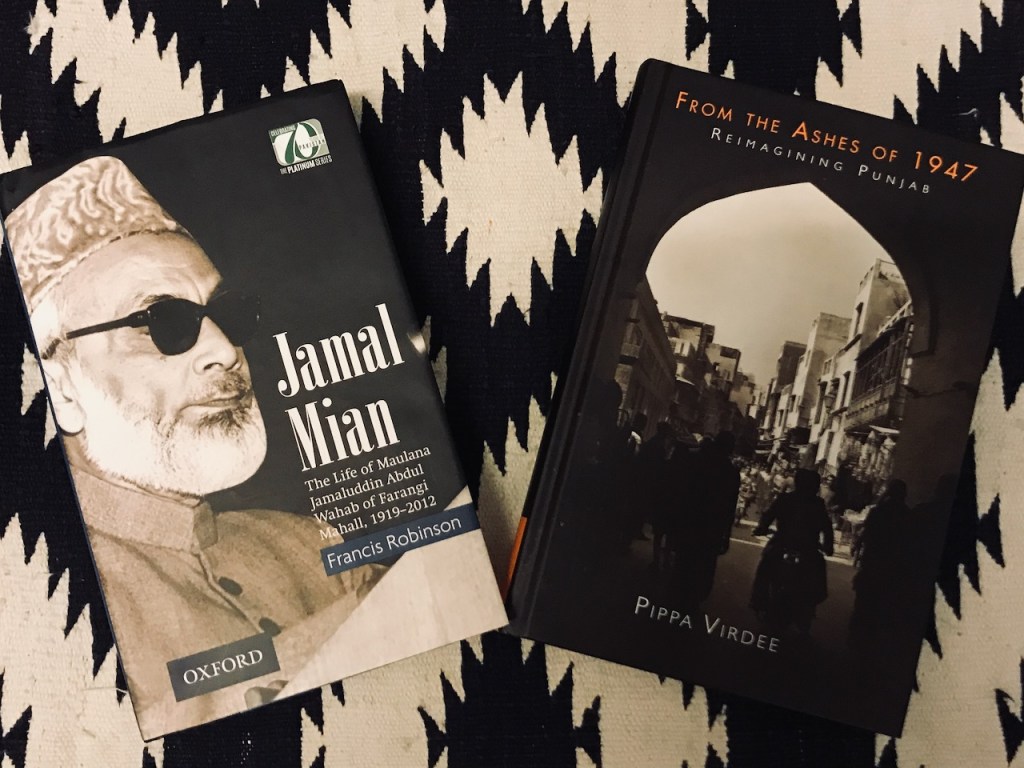

I was preparing for a forthcoming History conference in Lyallpur when I started browsing and jumped from one rabbit hole to another. Sometimes research is like that, you need to explore and get lost in the lanes of history to find something. I did get the inspiration I wanted but I also ended up with more information than I needed. Amongst all of this is a list of some well-known people who were born in Ludhiana or Lyallpur. I was more interested in the direct links between these cities and the people that migrated between these two, as my I have a long-standing research and personal interest in both cities. However, those links were not always present, but it is still interesting to see the kind of people who emerged from these localities and migrated following the Partition.

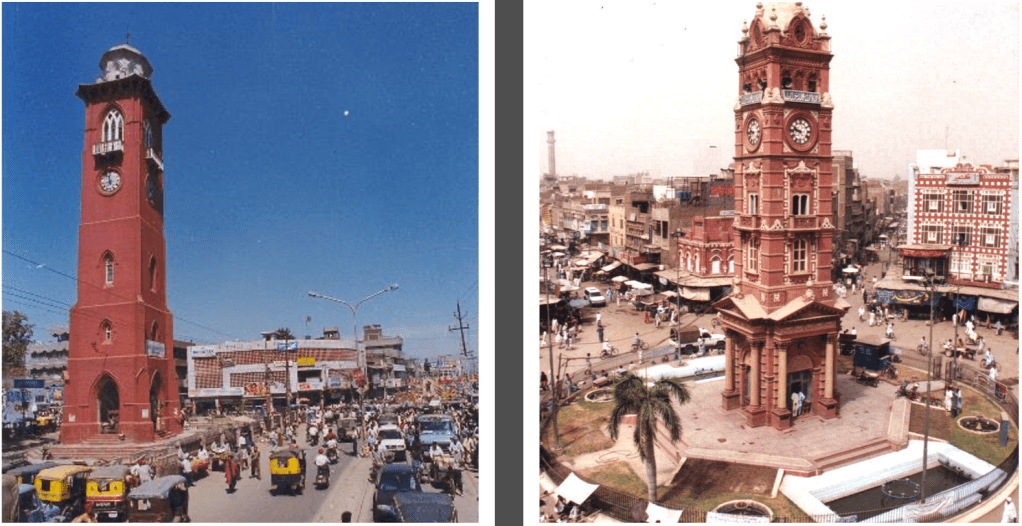

Ludhiana and Lyallpur were in fact only small towns before Partition, and interestingly both have iconic colonial clock towers in the town centre; both are important industrial textile hubs in the region; both had 62% ‘other’ populations prior to 1947 (according to the 1941 census, 62% Muslims lived in Ludhiana and 62% Sikhs/Hindus in Lyallpur); and finally, both function as important diasporic cities in contemporary Punjab(s).

Typically I tried to find women, but sadly the list of people is mostly male bar two! I hope to continue adding to the list as I find more people or please leave a comment if you know any other people with Ludhiana-Lyallpur links.

Note: the source for the information below is mainly through browsing and do not claim it as my own work. I have only selected a people I was interested in and that were born before 1947 and migrated following the Partition.

From Ludhiana…

Abu Anees Muhammad Barkat Ali Ludhianvi (1911 – 1997) was a Muslim Sufi who belonged to the Qadiri spiritual order. He was the founder of the non-political, non-profit, religious organisation, Dar-ul-Ehsan. Abu Anees’s followers spread all around the world and especially in Pakistan. He was born in Ludhiana where his father was a landlord.

Agha Ali Abbas Qizilbash also known as Agha Talish, (1923 –1998) was a Pakistani actor who made his debut in 1947 and was mostly known and recognized in Pakistan for playing character actor or villain roles. Talish was honoured by a Pride of Performance award, by the Government of Pakistan in 1989. Talish was born in Ludhiana, and his breakthrough film in Pakistan was film producer Saifuddin Saif’s Saat Lakh (1957) where his on-screen performance for this popular hit song was widely admired, Yaaro Mujhe Maaf Rakho Mein Nashe Mein Hoon.

Ajaz Anwar (1946-) is a Pakistani painter. He was a gold medalist at Punjab University, and he completed his M.A. in Fine Arts from Punjab University. Later, he went to teach at National College of Arts Lahore. His watercolour paintings show the grandeur of the old buildings and the cultural life in Lahore. Born in Ludhiana in 1946, his father was a cartoonist who apparently had stirred his passion from childhood and from whom he drew his inspiration.

Anwar Ali (1922-2004) was a Pakistani Editorial Newspaper Cartoonist in Pakistan Times based in Lahore. Anwar Ali was the creator of famous character Nanna, was the first newspaper cartoonist associated with The Pakistan Times. He was born in Ludhiana, where he spent his childhood. He did his BA from Government College Ludhiana.

Chaudhary Abdul Hayee Gujjar (1921 – 1980), popularly known by his pen name Sahir Ludhianvi, was an Indian poet who wrote primarily in Urdu in addition to Hindi. He is regarded as one of the greatest film lyricists and poets of twentieth century India. Sahir was born in Karimpura, Ludhiana to a Punjabi Muslim Gujjar family.

Habib-ur-Rehman Ludhianvi (1892 – 1956) was one of the founders of Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam. He belonged to an Arain (tribe) and was a direct lineal descendant of Shah Abdul Qadir Ludhianvi, the freedom fighter against British Colonial rule during the Indian Rebellion of 1857. He chose to stay back in Ludhiana to continue representing the thousands of Muslims still remaining there after the partition in August 1947. The ancestral masjid in Field Ganj still exists today.

Hameed Akhtar (1923 – 2011), was a newspaper columnist, writer, journalist and the secretary-general of the Progressive Writers Association in Pakistan. He was also the father of TV actresses Saba Hameed, Huma Hameed and Lalarukh Hameed. He finished his basic education in Ludhiana and was a childhood friend of renowned poets Sahir Ludhianvi and Ibn-e-Insha

Munawar Sultana (1924- 1995) was born in Ludhiana and was a Pakistani radio and film singer. She is known for vocalizing first ever hit Lollywood songs like, “Mainu Rab Di Soun Tere Naal Piyar Ho Gya” (Film: Pheray 1949), “Wastae Rab Da Tu Jaanvi We Kabootra” (Film: Dulla Bhatti 1956),and “Ae Qaid-e-Azam, Tera Ehsan Hay, Ehsan” (Film: Bedari 1957).

Saadat Hasan Manto (1912 – 1955) was a Pakistani writer, playwright and author who was active in British India and later, after the 1947 partition of India, in Pakistan. Saadat Hassan Manto was born in Paproudi village of Samrala, in Ludhiana district to a Muslim family of barristers. Ethnically the family were Kashmiri.

From Lyallpur

Grahanandan Nandy Singh (1926 – 2014) was an Indian field hockey player who won two gold medals, at the 1948 and 1952 Summer Olympics. There is a documentary film on the team by Bani Singh titled, ‘Taangh/Longing’. Singh began playing hockey while studying at the Government College in Lahore, serving as captain of their hockey team in 1945 and 1946. After the Partition, he moved to Calcutta and played for Bengal when he was selected to the 1948 Indian Olympic team.

Harnam Singh Rawail (1921 – 2004), often credited as H. S. Rawail, was an Indian filmmaker. He debuted as a director with the 1940 Bollywood film Dorangia Daku and is best known for romantic films like Mere Mehboob (1963), Sunghursh (1968), Mehboob Ki Mehndi (1971) and Laila Majnu (1976). Rawail was born in Lyallpur and moved to Mumbai to become a filmmaker.

Inderjeet Singh (1926 –2023), also known as Imroz, was an Indian visual artist and poet. He was the partner of the poet, novelist, and writer Amrita Pritam, and they lived together until Amrita’s death in 2005. Inderjeet Singh was born in Chak number 36, Lyallpur.

Jagjit Singh Lyallpuri (1917 –2013) was an Indian politician. He was the oldest surviving member of the founding Central Committee of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). Prior to the Partition of India, Lyallpuri’s family owned roughly 150–180 acres in Lyallpur. The family moved to Ludhiana following the Partition.

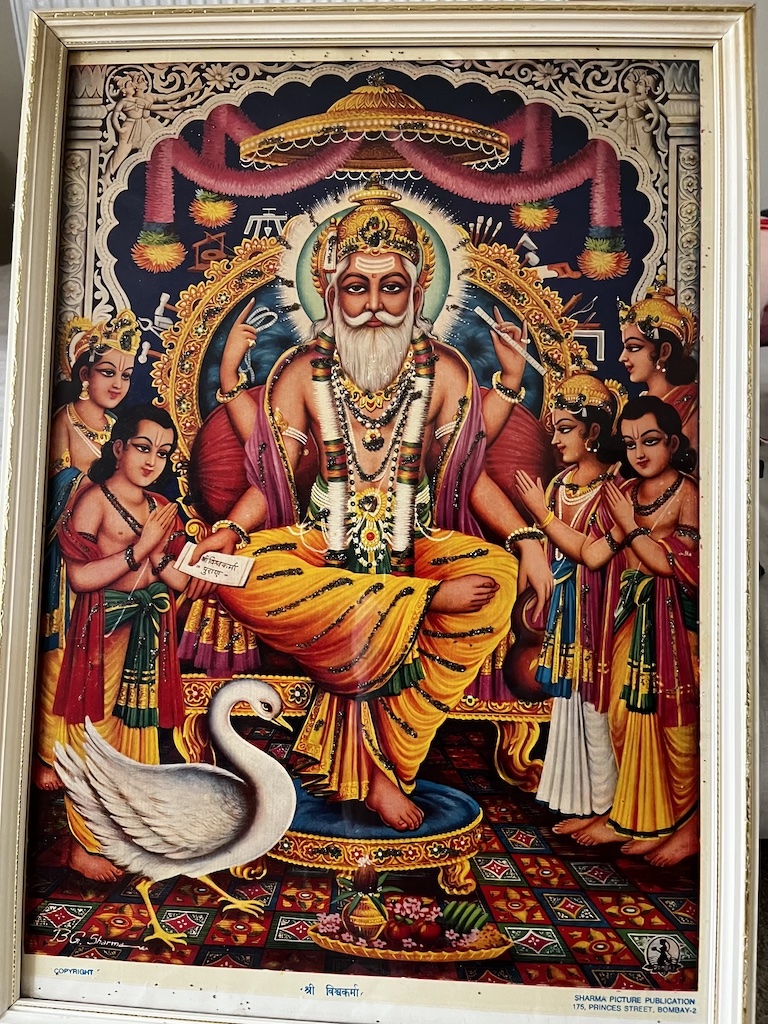

Jaswant Rai Sharma (1928 –2017), popularly known by his pen name Naqsh Lyallpuri, was an Indian ghazal and Bollywood film lyricist. He is best known for the songs “Rasm-e-Ulfat Ko Nibhayen” (Dil Ki Rahen, 1973), “Ulfat Mein Zamaane Ki” (Call Girl, 1974), “Tumhe Ho Na Ho” (Gharonda, 1977), “Yeh Mulaqaat Ek Bahana Hai ” (Khandaan, 1979), “Pyar Ka Dard Hai” (Dard, 1981), and “Chitthiye Ni Dard Firaaq Vaaliye” (Henna, 1991). He was born in Lyallpur to a Punjabi Brahmin family, where his father was a mechanical engineer.

Lal Chand Yamla Jatt (1910 – 1991) was a noted Indian folk singer in the Punjabi-language. His trademark was his soft strumming of the tumbi and his turban tying style known traditionally as “Turla”. Many consider him to be the pinnacle of the Punjabi music and an artist who arguably laid the foundation of contemporary Punjabi music in India. He was born to Khera Ram and Harnam Kaur in Chak No. 384, Lyallpur. After partition, they relocated to the Jawahar Nagar, Ludhiana.

Prithviraj Kapoor (1906 –1972) was an Indian actor who is also considered to be one of the founding figures of Hindi cinema. He was associated with Indian People’s Theatre Association as one of its founding members and established the Prithvi Theatres in 1944 as a travelling theatre company based in Bombay. He was born in Samundri into a Punjabi Hindu Khatri family. His father, Dewan Basheshwarnath Kapoor, was a police officer in the Indian Imperial Police. His grandfather, Dewan Keshavmal Kapoor, and his great-grandfather, Dewan Murli Mal Kapoor, were Tehsildars in Samundri near Lyallpur.

Romesh Chandra (1919 – 2016) was a leader of the Communist Party of India (CPI). He took part in the Indian independence struggle as student leader of CPI after joining it in 1939. He held various posts within the party. He became president of the World Peace Council in 1977. He was born in Lyallpur and got his degree in Lahore and another one from Cambridge.

S.D. Narang (1918-1986) was born in Lyallpur. He was a director and producer, known for Dilli Ka Thug (1958), Anmol Moti (1969) and Shehnai (1964). He graduated in Biology from Government College, Lahore and did his MBBS from King Medical Collage, Lahore.

Sunder Singh Lyallpuri (1878 – 1969) was a leading Sikh member of the Indian independence movement, a general of the Akali Movement, an educationist, and journalist. Lyallpuri played a key role in the development of the Shiromani Akali Dal, and in the Gurdwara Reform Movement of the early 1920s and also founding member of Central Sikh League.

Teji Harivansh Rai Srivastava Bachchan (1914 – 2007) was an Indian social activist, the wife of Hindi poet Harivansh Rai Bachchan and mother of Bollywood actor Amitabh Bachchan. Teji was Born into a Punjabi Sikh Khatri family in Lyallpur.