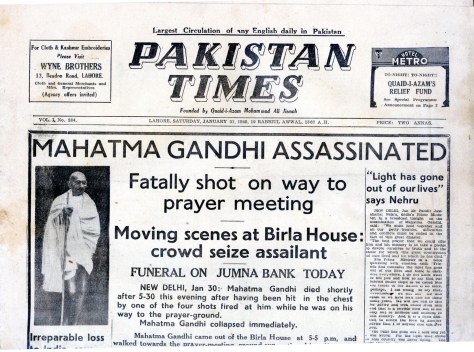

In 1948 Faiz Ahmed Faiz was the editor of The Pakistan Times. Following the assassination of Gandhi on 30 January 1948, he wrote the following editorial. It is a useful reminder of the challenges still facing India today. The RSS was founded in 1925 and banned on 4 February 1948 following Gandhi’s assassination, this remained in place until 11 July 1948. The ban was lifted once the RSS accepted the sanctity of the Constitution of India and respect towards the National Flag of India, both of which had to be explicit in the Constitution of the RSS.

In 1948 Faiz Ahmed Faiz was the editor of The Pakistan Times. Following the assassination of Gandhi on 30 January 1948, he wrote the following editorial. It is a useful reminder of the challenges still facing India today. The RSS was founded in 1925 and banned on 4 February 1948 following Gandhi’s assassination, this remained in place until 11 July 1948. The ban was lifted once the RSS accepted the sanctity of the Constitution of India and respect towards the National Flag of India, both of which had to be explicit in the Constitution of the RSS.

The Pakistan Times, Lahore. 6 February 1948

Five days after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian Government has taken the first concrete step forward and banned the RSSS throughout the territories of the Indian Dominion. This has followed the resolution adopted by the Indian Cabinet on February 2 which declared the Government’s determination ‘to root out the forces of hate and violence that are at work in our country and imperil the freedom of the nation and darken her fair name.’ The communique issued by the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs announcing the ban further states that the RSSS have been found circulating leaflets exhorting people to resort to terroristic methods, to collect fire arms to create disaffection against the Government and suborn the police and the military. The Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh has been functioning for many years now and under the garb of promoting the spiritual and physical well-being of the Hindus has organised itself as a militant fascist party, preaching hatred and spreading the cult of violence. When the recent phase of communal rioting started the RSSS with its other allies regarded it as an opportune moment to make a bid for power. As blood continued to flow and innocent heads hit the dust, as women were dishonoured and infants mercilessly butchered, the RSSS went from strength to strength. By the end of last year it had spread its tentacles to every Indian city and Province. Its propaganda reached every Hindu; it had not only a considerable mass following but succeeded in making influential friends in the Government in both the services and the Central and Provincial Cabinets. Nor was the Congress organisation free from its corroding influence. The Indian Government were not unaware of the part that the RSSS had played in the Punjab and else where. They were aware of its growing influence and must also have known of the conspiracy against the Central Government, of which the extermination of Indian Muslims and the murder of Mahatma Gandhi were a part. But even as late as November last year, at an All-India conference of Home Ministers, it was decided that no action should be taken against the RSSS as such but only those of its members who infringed the law of the land should be dealt with. This policy of drift and vacillations has taken a heavy toll; not only have thousands of innocent persons been killed and millions rendered homeless but India and the world have lost one of their greatest men. All this need not have been if the leaders in the Government of India had shown a fraction of the courage and vision of Mahatma Gandhi. The question which is agitating the minds of the people, not only in India and Pakistan but throughout the world today, is: what the future who will win? The dregs of Indian society who distributed sweets when the tragic event took place, have not given up the struggle and intend to lie low for some time so that the people’s sorrow is forgotten, their anger vitiated by direct action against a few scape-goats and their demand for a purge of the administration side-tracked by talk of ‘unity in the face of disaster’ and other meaningless slogans. Or will final victory still lie with Mahatma Gandhi and the millions in the country who support his aims and ideals? The first decision of the Government in this connection has received wide welcome. But it is universally felt that only if this decision is regarded by the Nehru Government as the first step in the fight against the forces of evil and darkness, then alone might we see the completion of the noble work for which Mahatma Gandhi died. If, however, it is the only step and after a few weeks or months the RSSS, under some other name, raises its ugly head, and its allies, the Hindu Mahasabha, the Akali party and the Princes are allowed to exist and stage a comeback of their perverted ideology then the future is dark and dismal and the Mahatma has lived and died in vain. The new Nehru-Patel unity, which was trumpeted in the recent meeting of the Congress Party in the Constituent Assembly is likely to lead to confusion, unless it is made clear that it is based on a definite agreement to carry out in toto Gandhiji’s policy and to give no quarter to the rabid communalists who have caused such great disasters. Much, of course, depends on the common people of India who know that their beloved leader’s murder was definitely not the ‘act of a foolish young man’ as Master Tara Singh and his like would have them believe, but a part of the huge conspiracy, which seeks to put in power the worst reactionaries in the land. In this struggle for the ideals for which Mahatma Gandhi stood, we in Pakistan are vitally concerned and have an important part to play. For the future of both peoples and both countries is inextricably linked together, and to the extent that we base our future policies on the last will and testament of Mahatma Gandhi-that without communal amity and without Indo-Pakistan accord there can be neither freedom nor progress for either-to that extent is the future happiness and prosperity of this sub-continent assured.

Editorial available in Faiẓ, Faiẓ Aḥmad, and Sheema Majid. Coming Back Home: Selected Articles, Editorials, and Interviews of Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Oxford University Press, 2008.