Harinder Bindu and Sonia Mann have become prominent faces at the ongoing farmers’ movement. Both Bindu and Mann’s fathers were gunned down by Khalistanis during the militancy in Punjab, in the early 1990s. “What does this society think of women? This society’s Manusmriti, its religious institutions, and its other institutions, they think that ‘Women have no wisdom. They should be kept under our shoes,’” Bindu said. “But we say ‘No.’ Women are equal to men and they too have the right to struggle. For a life of equality, for a good life, they should fight.” “They [the government] are the ones operating like terrorists,” Mann said. “They are the ones shooting cold water [from water canons] at us and our elders, throwing tear gas at them, and hurting them [elders].” Shahid Tantray reports. Camera by CK Vijayakumar and Tantray. #FarmersProtest

Category Archives: India

Guru ka langar

One of the earliest pieces I started with on this blog was with this picture of Guru ka Langar (or food for the congregation) in Lahore. The simplicity of daal (lentils) or in this case rajma (kidney beans) with roti (bread) is the basis of most langar served in a Gurdwara. As a child, I remember most children enjoyed going there in part because of the karah parshad (sweet halwa made from whole wheat flour) given at the end of the service and followed by the (free) food, which had its own distinctive divine taste, impossible to recreate at home.

Langar is the communal partaking of food when visiting Gurdwara. The concept has in recent years been popularised globally by Sikh organisations such as Khalsa Aid, which plan, produce and distribute langar to people across the crisis-ridden world, be it to the truckers stranded in Dover over the ongoing Christmas period or in recent war-torn Syria. With Langar spreading so does knowledge about and experience of the Sikh community. Currently, closer to the home of Sikhism in Punjab, Langar has been making headlines via the ongoing farmers’ movement against new farm laws in India. Communal kitchens have been set-up by the roadside to feed the thousands gathered on the borders of capital, Delhi.

Origins

The word ‘langar’ (meaning ‘anchor’) is thought to have come into the Punjabi language from Persian (Nesbitt: 29); although the idea was not unique to the Sikhs, as ‘both the Sufis and the Nath Yogis have a system of collective eating (langar khanah and bhandaras). The Sikhs, however, used it as venue for both service and charity and provided the food themselves [unlike] the Nath Yogis, who begged for food, and the Sufis, who often accepted land-grants to run their kitchens’ (Mann: 27).

Pictures are of Gurdwara Sacha Sauda, Farooqabad, Pakistan and about 37 miles away from Lahore. This gurdwara is revered with the origins of the langar and is situated not far from Nankana Sahib, the birth place of Guru Nanak.

Baba Farid (1170s-1260s), a Sufi saint from the Chishti order, living in the Punjab, would distribute sweets amongst his visitors; a precursor to langar-khana near shrines, a practice documented in Jawahir al-Faridi (1620s) by a descendent of his. The khanqahs of the Chishti and other Sufi orders kept a langar open for the needy, but also others. It is said that ‘Khwaja Muinuddin established the tradition of an open kitchen for all who came…in an age of feudalism and violence’ (Talib: 6).

There is, of course, a much older practice of the alms house or dharmshala/sarai to feed travellers and poor for free, which is thought to have existed through the Gupta and Maurya (esp. Buddhist) times that is on either side of the BC/AD divide.

Faith

The connections between the Sufis and the Bhakti (devotional) traditions are well documented, inspired as both were by the idea of feeding the poor, the pilgrim and thereby removing divisions/discrimination among people. The idea concretised with the rooting of faith in the region and by early 17th century, it had become a recognised Sikh fixture (Desjardins).

Eleanor Nesbitt notes that, ‘in institutional terms, it was the third Guru, Amar Das [1479-1574], who gave prominence to the langar… [integral as] sharing food [was] to Guru Nanak’s Kartarpur community…it was Guru Amar Das who particularly emphasised the requirement for everyone to dine side by side, regardless of caste and rank’ (Desjardins: 29).

There were two women, who especially, ‘nurtured the development of the langar tradition in its formative period: Mata Khivi (1506-82) and Mata Sundri, the second and tenth Gurus’ wives’. The Guru Granth Sahib notes that ‘Khivi…is a noble woman, who…distributes the bounty of the Guru’s langar; the kheer—the rice pudding and ghee—is like sweet ambrosia’. After the death of Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708), ‘his widow Mata Sundri worked hard to continue the free community kitchen service. Records show her active role in fundraising for this purpose when the very survival of Sikhism was in question… (Desjardins).

The langar since is thus an integral part of the faith/religion, its compassion through the concept of Seva (self-less service); essential for all practicing Sikhs. Donating food or money is not as important as the practice of giving one’s time and service. Today the most famous community kitchen serving langar has to be the Golden Temple (Amritsar), where around 100,000 people are served on a daily basis. However, most Sikhs grow up visiting and worshipping at small local gurdwaras, where everyday worshippers and volunteers prepare food on a daily basis. These photos are taken from the local gurdwara at Mao Sahib (my father’s village, Jalandhar district), where the congregation prepare, serve, consume the langar and then clean afterwards. As the gurdwaras become more institutionalised, and as the historic gurdwara Mao Sahib (associated with the fifth Guru Arjan and his consort Mata Ganga, d. 1621) has come under the administration of the SGPC (the Sikh body responsible for the management of gurdwaras), voluntary seva has been added to by paid sevadars.

The pictures are of Mao Sahib, 2012, when the langar hall was undergoing a renovation and some of the langar preparation was taking place outside.

Equality

The idea of sitting and sharing food together is fundamental among Sikhs because it demonstrates the abolition of caste and dramatically asserts humble equality amongst all the people; regardless of their religious or caste background. The food is generally simple and vegetarian, to appeal to all and offend no one. Four core Sikh principles are enshrined in the langar: equality, hospitality, service, and charity.

Eleanor Nesbitt writes about how, ‘the Gurus were reformers who abolished the caste system or that caste is Hindu, not Sikh’. It is important to remember how revolutionary this was/is in a caste-ridden society. Nesbitt notes how, ‘the langar subverted Brahminical rules about commensality, according to which only caste fellows could eat together’ (118). Instead, it was proclaimed that, ‘a Sikh should be a Brahmin in piety, a Kshatriya in defence of truth and the oppressed, a Vaishya in business acumen and hard work, and a Shudra in serving humanity. A Sikh should be all castes in one person, who should be above caste’ (117). The Gurus, like the Bhagats Namdev, Kabir, and Ravidas, proclaimed the irrelevance of people’s inherited status to their spiritual destiny. In Guru Nanak’s view:

Worthless is caste (Jati) and worthless an exalted name,

For all humanity there is but a single refuge (Adi Granth 83)

Quoted in Nesbitt: 118

Similarly, according to Guru Amar Das:

When you die you do not carry your Jati with you:

It is your deeds which determine your fate. (Adi Granth 363)

Quoted in Nesbitt: 118

References

Bowker, John (ed.), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions (OUP, 1997)

Desjardins, Michel, and Ellen Desjardins, ‘Food that builds community: the Sikh Langar in Canada’, Cuizine: The Journal of Canadian Food Cultures/Cuizine: revue des cultures culinaires au Canada 1, no. 2 (2009) https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/cuizine/2009-v1-n2-cuizine3336/037851ar/

Mann, Gurinder Singh, Sikhism (Prentice Hall, 2004)

Nesbitt, Eleanor, Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2016)

Talib, Gurbachan Singh, Baba Sheikh Farid Shakar Ganj (NBT India, 1974)

More about Gurdwara Sacha Sauda: http://pakgeotagging.blogspot.com/2018/02/084-gurdwara-sacha-sauda-farooqabad.html

The Making of the Indian Middle-Class

Nothing has captured contemporary adjectives around India more than its seemingly inevitable and irresistible MIDDLE-CLASS; a cursory survey yields an expansive collection of studies on the subject. The key question in them often is how to define this broad category.

According to Abhijit Roy and based on data by “the World Bank and the Organization for the Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), for those in the middle classes, the earnings typically lie in the range of US $10 to $100 per day, as expressed in the 2015 purchasing power parities”. Using the India Human Development Survey II (2011–12), Maryam Aslany reveals significant findings about the Indian middle class:

“(1) It calculates the size of the middle class to be 28.05% of the urban and rural population. (2) It demonstrates that despite the occupational diversity that exists, a large proportion of the middle class are salaried employees. (3) It demonstrates that contrary to common assumptions, a considerable segment of the Indian middle class resides in rural areas. (4) The fastest growth is in the lower middle classes, who spend between US $4 and $6 per day. This group includes carpenters, street vendors, decorators and drivers”.

Statistical evidence aside, one of the key elements of a middle class is how this class shifts from need to want – a key component of the capitalist model, which creates the desire to consume something, even when it is not required. This is an aspirational desire and in India, the strong connection to society/samaaj ensures that this “want and desire” has a strong market, from whose epicentre – Bombay/Mumbai – economists have defined the middle class as “consumers spending from US $2 to $10 per capita per day. By this definition, approximately half of India’s population of 1.3 billion is in the middle class” (Roy).

Employable education is often seen as one of the key routes to this upward mobility. But once successful, there is also potentially a “tussle between individuality and community: seeking novel self-expression in new jobs and leisure or taking risks with autonomy (the divorce rate is growing, from a low base), but also attempting to keep a sense of community, with dutiful support of parents (a high number of IT professionals buy cars for their parents) and strenuous attempts at maintaining a social circle (oriented around alcohol, movies, resorts and restaurants)” (Ram-Prasad).

One of the challenges with understanding how class works in India is the overlaps with caste. It is often difficult to disaggregate the two. “Upper-caste elites have, in recent decades, become used to those below them in the hierarchy accruing economic power, especially since liberalisation in the early 1990s. The new middle class argues that since it had no help from older elites, its success is self-made and ought to be the model for the poor. But the poor are still usually from castes traditionally lower than those of the new middle class—and this acts as an obstacle to their advancement” (Ram-Prasad).

One of the key things that I have observed over my three decades of travelling to India is the shift in people’s attitude after the liberalisation of the economy. Over a period of time, an airy sense of arrogance, importance and arrival at the global stage has replaced the grounded humility, self-reflection and non-aggression that had wider traction. In part, these attitudes can be traced back to the freedom movement and it is interesting to reflect back to when India had only recently gained independence.

The following extracts from G. L. Mehta, a long-serving Indian Ambassador to America in the mid-1950s, highlight the then- “numerical insignificance” of this ubiquitous group of the middle classes:

“In India, government officials, professional men like lawyers and doctors, technicians and teachers, shop-keepers and clerks are all part of the inchoate group, which goes by the name of “middle classes”. Although merchant classes and officials in medieval India were a group, the middle classes are of a comparatively recent origin. In a society, where caste and status determined the social structure, the middle-income group did not wield any political power nor did they enjoy any social prestige…

…the rise of the middle classes has been due as much to the advent of foreign rule as to the impact of economic forces…There is no gainsaying the fact that our national movement has had its origin and impulse from the middle class. Indeed, the leaders of the labour movement have also been drawn mostly from the middle classes. These classes have largely helped to make India what it is, both in its strength and in its weaknesses…

…the striking fact, however, is their numerical insignificance. An examination of the income-tax statistics shows that in the Indian Union, the numbers of those earning between Rs. 300/- and Rs. 2000/- per month add up to only a little over 3 lakhs. Allowing for 5 dependents to every income earner, it would appear from this that the core of the middle classes in India consists of less than 2 million out of 350 million people…

…in 1938-39, their share of the national income was roughly 5%; today their share is more 3 ½-4%. While the rising prices of the last decade have created higher incomes and pushed up people, it is only a few in the upper income groups, who have stood to gain. Those earning between Rs. 500/- and Rs. 1000/- per month had an annual income of Rs. 80 crores in 1948-49 compared to Rs. 50 crores in 1938-39 but those in Rs. 1000/- and Rs. 2000/- group had Rs. 100 crores in 1948-49 compared to Rs. 30 crores in 1938-39 and those with incomes of Rs. 2000/- per month shared nearly Rs. 160 crores in 1948-49 compared to Rs. 30 crores in 1938-39…

…these distributional changes, together with the general stagnation in the economy, have created a situation of great stress and strain. The middle classes have, on the whole, stopped recruiting from below. Unless the middle classes can improve their economic condition in pace with the growth in their numbers, they are bound to suffer frustration and disillusionment, in proportion with unemployment and inflation. As the London Economist said recently commenting on the situation in India, “when the shop-keeper flourishes and the clerk starves, revolution is round the corner, for the educated middle class will tolerate only so much” (!)…

…but the future of a class, which is not allied to any special interest in uncertain. Equally, if the middle classes are to maintain their leadership, they should avoid freezing into a static group. They will have, therefore, to absorb continuously waves of people ascending from the ranks of peasants, artisans and labourers. At the other end they would have also to discard those whose stakes in the system are so great that they become an impediment to change…because the middle class, and its professional core in particular, can check the acquisitive instincts of the Economic Man. Perhaps it may be the role of the middle-class, to show us the middle way between freedom and order, enterprise and social security”.

References:

Above extracts from an All-India Radio talk, 14 January 1951 by G.L. Mehta (A Many Splendoured Man, Aparna Basu, 2001)

Maryam Aslany, ‘The Indian middle class, its size, and urban-rural variations’, Contemporary South Asia, 2019, 27:2, 196-213, DOI: 10.1080/09584935.2019.1581727

Abhijit Roy, ‘The Middle Class in India: From 1947 to the Present and Beyond’, Spring 2018. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-middle-class-in-india-from-1947-to-the-present-and-beyond/

Ram-Prasad Chakravarthi, ‘India’s middle-class failure’, 30 September 2007. https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/indias-middle-class-failure

Brant Moscovitch, ‘A Liberal Ghost? The Left, Liberal Democracy and the Legacy of Harold Laski’s Teaching,’ The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 2018, 46:5, 935-957, DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2018.1519245

1984: Who are the Guilty?

Following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh Bodyguards on 31 October 1984, parts of Delhi, North India and other areas with Sikh populations became engulfed in an anti-Sikh pogrom. From 31 October to 3 November 1984 in the national capital, organised violence against the Sikh community was unleashed, unlike anything it had witnessed previously since the anti-Muslim carnage of September 1947. The ‘official’ claim later was that 2,800 Sikhs were killed in Delhi and 3,350 elsewhere in the country. However, independent sources suggest a much high figure. Among these, one of the first to come out was this fact-finding report by political scientist Rajni Kothari of the People’s Union For Civil Liberties and Gobinda Mukhoty of the People’s Union for Democratic Rights, which investigated the murders, looting and rioting that took place during those 10 days and published it later the same month. It starkly concluded that:

…the attacks on members of the Sikh Community in Delhi and its suburbs during the period, far from being a spontaneous expression of “madness” and of popular “grief and anger” at Mrs. Gandhi’s assassination, as made out to be by the authorities, were the outcome of a well organised plan marked by acts of both deliberate commissions and omissions by important politicians of the Congress (I) at the top and by authorities in the administration. Although there was indeed popular shock, grief and anger, the violence that followed was the handiwork of a determined group which was inspired by different sentiments altogether.

Further reading:

Manoj, Mitta & H S Phoolka. When a tree shook Delhi: the 1984 carnage and its aftermath. Lotus. 2007.

Mukhopadhyay, Nilanjan. Sikhs: The Untold Agony of 1984. Westland, 2015.

Pandey, Gyanendra. “Partition and Independence in Delhi: 1947-48.” Economic and Political Weekly (1997): 2261-2272.

Suri, Sanjay. 1984: The Anti-Sikh Riots and After. HarperCollins, 2015.

History and History Writing

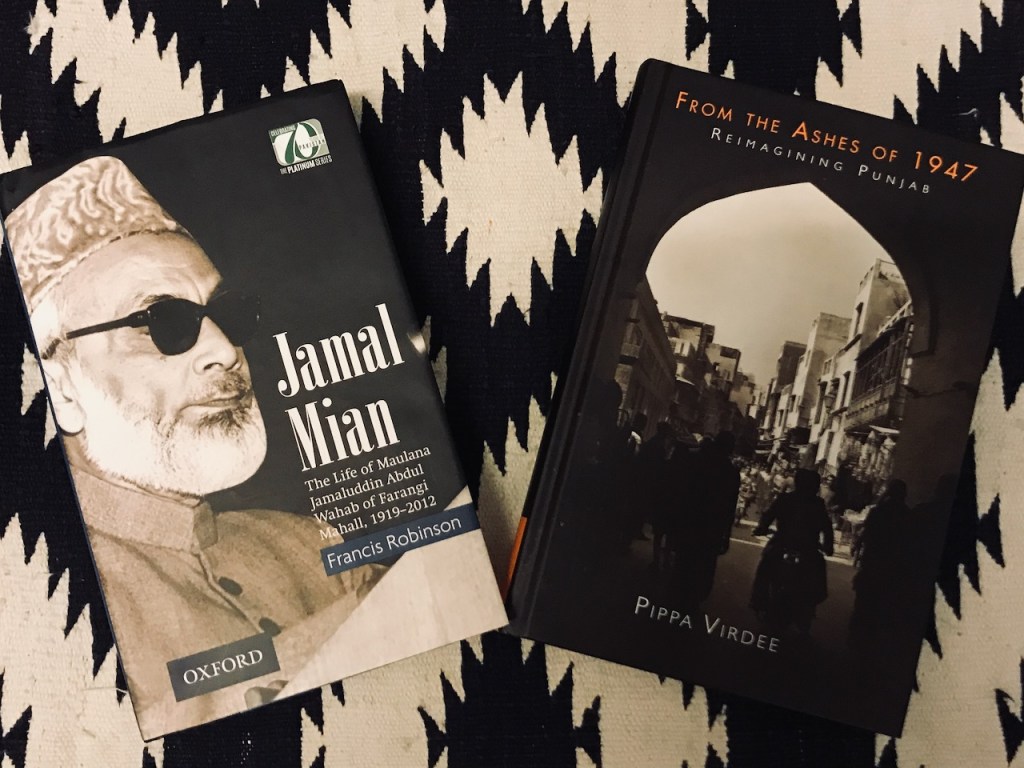

TWO books reviewed of A time BYGONE

ONE is the biography of Jamal Mian (1919-2012), a life across British India, independent India, East Pakistan and Pakistan. The kind of life, which would be unimaginable to most people of the subcontinent today. At the core, this is a detailed history of the changing political landscape of North India told through the life and times of an extraordinary life. The story unfolds with authority and simplicity, the kind of old-fashioned narrative history writing that barely exists. Stories and history writing are barely written like like because they do not command the short-term impact and they take years, generations to unfold through the relationship of the historian and his subject. But importantly it brings together the life and times of an individual and his milieu – showcasing the kind of “Hindustan” that no longer exists, other than in history books.

Pippa Virdee, FRANCIS ROBINSON. Jamal Mian: The Life of Maulana Jamaluddin Abdul Wahab of Farangi Mahall, 1919–2012, The English Historical Review, ceaa186, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ceaa186

TWO is an account of the province(s) of Punjab; rising From the Ashes of 1947 but simultaneously being reimagined. This too is about a political landscape that has been transformed and only exists in the history books, kinder memories and sepia imaginations of some of its people. It is about the shorter, shocking and longer, hardening consequences of dividing the land of five rivers. It too has been written over a long period and reveals the changing nature of my understanding of Partition, from the beginning of my doctoral work in 2000, to the point of this publication in 2017. It has changed further still because history is about engaging with the past through the unfolding present and “reveals how far nostalgia combined with the lingering aftershocks of trauma and displacement have shaped memories and identities in the decades since 1947.”

Sarah Ansari, PIPPA VIRDEE. From the Ashes of 1947: Reimagining Punjab, The American Historical Review, Volume 125, Issue 2, April 2020, Pages 635–636, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhz695

The Persistence of Caste

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (14 April 1891 – 6 December 1956)

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji, and Frances W. Pritchett. Pakistan or Partition of India. Thacker, 1946

The Muslim League’s Resolution on Pakistan has called forth different reactions. There are some who look upon it as a case of political measles to which a people in the infancy of their conscious unity and power are very liable. Others have taken it as a permanent frame of the Muslim mind and not merely a passing phase and have in consequence been greatly perturbed.The question is undoubtedly controversial. The issue is vital and there is no argument which has not been used in the controversy by one side to silence the other. Some argue that this demand for partitioning India into two political entities under separate national states staggers their imagination; others are so choked with a sense of righteous indignation at this wanton attempt to break the unity of a country, which, it is claimed, has stood as one for centuries, that their rage prevents them from giving expression to their thoughts. Others think that it need not be taken seriously. They treat it as a trifle and try to destroy it by shooting into it similes and metaphors. “You don’t cut your head to cure your headache,” “you don’t cut a baby into two because two women are engaged in fighting out a claim as to who its mother is,” are some of the analogies which are used to prove the absurdity of Pakistan. In a controversy carried on the plane of pure sentiment, there is nothing surprising if a dispassionate student finds more stupefaction and less understanding, more heat and less light, more ridicule and less seriousness. My position in this behalf is definite, if not singular. I do not think the demand for Pakistan is the result of mere political distemper, which will pass away with the efflux of time. As I read the situation, it seems to me that it is a characteristic in the biological sense of the term, which the Muslim body politic has developed in the same manner as an organism develops a characteristic. Whether it will survive or not, in the process of natural selection, must depend upon the forces that may become operative in the struggle for existence between Hindus and Musalmans. I am not staggered by Pakistan; I am not indignant about it; nor do I believe that it can be smashed by shooting into it similes and metaphors. Those who believe in shooting it by similes should remember that nonsense does not cease to be nonsense because it is put in rhyme, and that a metaphor is no argument though it be sometimes the gunpowder to drive one home and imbed it in memory. I believe that it would be neither wise nor possible to reject summarily a scheme if it has behind it the sentiment, if not the passionate support, of 90 p.c. Muslims of India. I have no doubt that the only proper attitude to Pakistan is to study it in all its aspects, to understand its implications and to form an intelligent judgement about it.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Annihilation of Caste: The annotated critical edition. Verso Books, 2014.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Annihilation of Caste: The annotated critical edition. Verso Books, 2014.

The Annihilation of Caste was an undelivered speech written in 1936 and to be delivered at the Jat-Pat Todak Mandal (Society for the Abolition of Caste system). However, the organiser found elements within the speech objectionable and Ambedkar refused to censor his words.

Roy, Arundhati, B. R. Ambedkar, and S. Anand. Annihilation of Caste: The Annotated Critical Edition. (2014).

Other contemporary abominations like apartheid, racism, sexism, economic imperialism and religious fundamentalism have been politically and intellectually challenged at international forums. How is it that the practice of caste in India – one of the most brutal modes of hierarchical social organisation that human society has known – has managed to escape similar scrutiny and censure? Perhaps because it has come to be so fused with Hinduism, and by extension with so much that is seen to be kind and good – mysticism, spiritualism, non-violence, tolerance, vegetarianism, Gandhi, yoga, backpackers, the Beatles – that, at least to outsider, it seems impossible to pry it loose and try to understand it.

Listen to The Doctor and The Saint: The Ambedkar—Gandhi debate: Race, Caste and Colonialism with Arundhati Roy (2014)

O’Boyle, Jane “The New York Times and the Times of London on India Independence Leaders Gandhi and Ambedkar, 1920–1948” American Journalism, Volume 35, 2018 – Issue 2, 214-235.

During the years before India’s independence, the Times of London published news stories that were derisive and skeptical of Mahatma Gandhi, reflecting a national policy to diminish his power in the process to “quit India.” The Times was respectful of the untouchables’ leader Bhimrao Ambedkar and his civil rights movement for untouchables, perhaps to further distract from Gandhi’s popularity. The New York Times lavished positive attention on Gandhi and largely ignored Ambedkar altogether. The American newspaper framed a hero of colonial independence and never his oppression of untouchables, adhering to news policy during the Jim Crow era of racial persecution.

Teltumbde, Anand. The Persistence of Caste: The Khairlanji murders and India’s hidden apartheid. Zed, 2010.

While the caste system has been formally abolished under the Indian Constitution, according to official statistics, every eighteen minutes a crime is committed in India on a Dalit-untouchable. The Persistence of Caste uses the shocking case of Khairlanji, the brutal murder of four members of a Dalit family in 2006, to explode the myth that caste no longer matters. In this exposé, Anand Teltumbde locates the crime within the political economy of post-Independence India and across the global Indian diaspora. This book demonstrates how caste has shown amazing resilience – surviving feudalism, capitalist industrialization and a republican constitution – to still be alive and well today, despite all denial, under neoliberal globalization.

Teltumbde, Anand. “Deconstructing Ambedkar,” Economic and Political Weekly (May 2, 2015).

Electoral politics became competitive bringing to the fore vote blocks in the form of castes and communities, both skilfully preserved in the Constitution in the name of social justice and religious reforms, respectively. The competing Ambedkar icons offered by various political manufacturers in India’s electoral market have completely overshadowed the real Ambedkar and decimated the potential weaponry of Dalit emancipation. The rhetoric of aggressive development, modernity, open competition, free market, etc, necessitated the projection of a new icon which would assure people, particularly those of the lower strata whom it would hit most, of the possibility of a transition from rags to riches with the adoption of the free-market paradigm.

Further Reading

Ministry of External Affairs (GoI): Writings & Speeches of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar https://www.mea.gov.in/books-writings-of-ambedkar.htm

Jaffrelot, Christophe. India’s silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. Orient Blackswan, 2003.

Jodhka, Surinder S. “Caste: why does it still matter?.” In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India, pp. 259-271. Routledge, 2015.

Pandey, Gyanendra. A history of prejudice: race, caste, and difference in India and the United States. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Padosi (1941) – Neighbour

Many times browsing through archives, especially the digital kind, leads you from one place to another. I was scanning the British Newspaper Archive for material related to the North-West Frontier of British India and ended up finding a small snippet in the Public Notices section of The Coventry Evening Telegraph on an Indian film, Padosi, hosted by the IWA at the Opera House in 1945.

The Indian Workers Association (IWA) was founded in 1938 in Coventry to mobilise for Indian independence amongst the small working-class Indian community living in the UK. Many of its early members were from Sikh and Muslim Punjabi backgrounds. Some of these members were sympathetic to and inspired by the Ghadr Party (est. 1913 in California). The British government naturally kept an eye on their activities; not only for their nationalist motivations but also for their leftist leanings. The extract below is taken from a document on the IWA, dated 14 April 1942.

The Hindi (or Hindustani) Mazdur Sabha, now more usually referred to as the Indian Workers’ Association (or union), has come gradually into being as a result of war conditions. In the two years preceding the outbreak of war a number of disaffected Sikhs – some of them with Ghadr Party contacts – who had come to the United Kingdom to work as pedlars decided to start, if possible, an organisation of Indians which should give all possible aid to the movement for Indian independence. At first the only practical step towards carrying out this decision were the secret collections and remittances to India of sums of money for payment to the dependents of political prisoners. The fund in India which received these sums of money was created by the Ghadr Party in California and there can be little doubt that the Indians in the UK who were chiefly interested in these collections were actuated by motives and by a long-range policy which were identical with these of the Ghadr Party. Some of them were in receipt of the “Hindustan Ghadr” until the close watch of the postal censorship succeeded in imposing an effective check on the entry of the paper into the UK. From the very beginning Coventry was the headquarters of the movement, for it so happened that the Indians chiefly interested were pedlars who sold their goods in the Coventry area. (File no. L/PJ/12/645)

Read further about the IWA:

Gill, Talvinder. “The Indian Workers’ Association Coventry 1938–1990: Political and Social Action.” South Asian History and Culture 4, no. 4 (2013): 554-573. DOI: 10.1080/19472498.2013.824683

Virdee, Pippa. Coming to Coventry: Stories from the South Asian Pioneers. The Herbert, 2006.

Communities in Action: the Indian Workers’ Association – Our Migration Story

Indian Workers’ Association – Making Britain

The film listed in the Public Notices snippet is “Parosi” (sic). This was a social drama directed by V. Shantaram and was set in the back drop of Hindu-Muslim unity. The Indian national movement was remarkably communalised in its last years, leading to unprecedented violence accompanying the end of British India. In 1941, it was unclear when and how this end would come. Alongside this rising tide of deteriorating inter-communal relations, there were progressive voices in the diversifying public sphere, now including cinema. One of these was the film’s legendary director, Shantaram, who pointedly got a Muslim actor to play a Hindu character and vice versa, to promote harmony between the communities. It is the type of film I imagine the IWA would want to show, as the organisation wished to emphasise class unity over communal politics in the battle against colonialism.

The Opera House in Coventry was opened in 1889. During World War II, the building was damaged by bombing but it was quickly repaired and transformed into a cinema when it re-opened in 1941. The Opera House closed in 1961 and, while there were plans to restore it to a live theatre venue, this never happened.

Read more about the former cinemas in Coventry.

Sahir Ludhianvi and the anguish of Nehruvian India

This song/poem written by Sahir Ludhianvi for the film Pyaasa, starring Guru Dutt, has as much relevance today as it did in 1957 at the height of the Nehruvian age. The lyrics and translation below are courtesy of Proud Indians, Are We? – Jinhe Naaz Hai Hind Par – Pyaasa By Deepa.

It is also worth reading the broader article, which is on Guru Dutt, “a man clearly ahead of his time.” Follow link for the song via YouTube. Make sure if you listen to any other versions that it has the last Antara of the song, which has been cut in some versions.

Ye kooche ye nilaam ghar dilkashi ke

Ye lutate huye caravan zindagi ke

Kahaan hain kahan hain muhafiz khudi ke

Jinhe naaz hai hind par wo kahaan hain

Kahaan hain kahaan hain kahaan hain

Look at these lanes, alluring houses which are up for sale/auction everyday. Look at these robbed caravans of life. Where are those protectors of self respect and pride? Where are those who say we are proud Indians? What are you exactly proud of?

Ye purpech galiyaan ye badnaam bazaar

Ye gumnaam raahi ye sikkon ki jhankaar

Ye ismat ke saude ye saudon pe taqraar

Jinhe naaz hai hind par wo kahaan hain

Kahaan hain kahaan hain kahaan hain

These complicated streets, these defamed, scandalized markets. The unknown pedestrians who walk in anytime with bagful of money. This trade of honour and chastity followed by the bargains of the same. Are we Indians proud for this? Where are those who say this?

Ye sadiyon se bekhauf sehmi si galiyaan

Ye masli huyi adhkhili zard kaliyaan

Ye bikti huyi khokhli rangraliyaan

Jinhe naaz hai hind par wo kahaan hain

Kahaan hain kahaan hain kahaan hain

These lanes which for years have been under pressure of fear, distress, angst. This place where the pale half blossomed buds are crushed (referring to young girls who fall prey to the flesh trade). The hollow festivities which are sold in this market. Show all this to those who say, they are proud of this country. Where are those people?

Wo ujle darichon mein paayal ki chhan chhan

Thaki haari saanson pe table ki dhandhan

Ye berooh kamron mein khaansi ki thanthan

Jinhe naaz hai hind par wo kahaan hain

Kahaan hain kahaan hain kahaan hain

The sound of the trinkets, anklets which come from the shimmering windows. Those tired, ill heartbeats which try to keep pace with the pace. This soul less room which filled with the unpleasant sound of coughing. For those who say they are proud Indians, please come and see this.

Ye phoolon ke gajre ye pikon ke chhinte

Ye bebaak nazrein ye gustaakh fiqrein

Ye dhalke badan aur ye bimar chehre

Jinhe naaz hai hind par wo kahaan hain

Kahaan hain kahaan hain kahaan hain

The flowers, the garlands, the stains of betel juice. The bold stares, the blunt, audacious comments. The deteriorating, decaying bodies and weak faces. Look at them, those who say, they are proud of their country.

Yahan piir bhi aa chuke hain jawaan bhi

Tanaumand bete bhi abba miyaan bhi

Ye biwi bhi hai aur behan bhi hai maa bhi

Jinhe naaz hai hind par wo kahaan hain

Kahaan hain kahaan hain kahaan hain

The ambassadors of religion, the young and the old, the sons and the fathers, all are regular visitors to this place. Here you will find someone’s wife, someone’s sister or mother too. Come and have a look at this place. Will this place make you proud?

Madad chaahti hai ye hawwa ki beti

Yashoda ki hamjins Radha ki beti

Payambar ki ummat Zulaykha ki beti

Jinhe naaz hai hind par wo kahaan hain

Kahaan hain kahaan hain kahaan hain

The girls, women here need help. They are no different from Eve, Yashoda, Radha, Zulaykha who are seen with regard and respect. Come and help them, they need you.

Zara mulk ke rahbaron ko bulaao

Ye kooche ye galiyaan ye manzar dikhaao

Jinhe naaz hai hind par unko laao

Jinhe naaz hai hind par wo kahaan hain

Kahaan hain kahaan hain kahaan hain

Someone please call the so called guides, leaders of the country. Show them these lanes, show them this miserable scene. Call them those who say they are proud of their country. Where are they?