One of the most famous jalebi shops in the city of Amritsar. This tiny little corner is food heaven for those with a sweet tooth. Nothing beats the freshly made hot, mouth-watering jalebis. Modest price, small portion and full of bliss! Go try them.

One of the most famous jalebi shops in the city of Amritsar. This tiny little corner is food heaven for those with a sweet tooth. Nothing beats the freshly made hot, mouth-watering jalebis. Modest price, small portion and full of bliss! Go try them.

Women’s World in The Pakistan Times, Sunday September 10, 1950.

Women’s World in The Pakistan Times, Sunday September 10, 1950.

Pakistanis in England by Christabel Taseer

On July last, after receiving the blessings of the Patron of the Pakistan Girl Guides Association, Miss Fatima Jinnah, the Pakistan delegation to the Thirteenth Session of the World Conference of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts at Oxford consisting of Begum Khalid Malik, Begum Taseer, Begum Abul Hassan and Mrs Pastakia, left Karachi by air. With us were our two Pakistani Girl Guides, Samina Anwar Ali and Nuzhat Mueenuddin, who were travelling to Switzerland to take part in a World Guide Camp organised by America. We reached Cairo, where we intended to break our journey for the night. As we passed through the Customs the Egyptian officials looked with great interest at our shalwars and qameezes.

“You are Pakistanis?” they asked.

We nodded.

Why are you going to England?” was the question.

“To take part in a ‘World Conference of Girl Guides at Oxford”, we replied.

Their faces were wreathing in smiles as they sald: “That’s excellent. Go and do your best, so that your country may be proud of you!” This was our first personal experience of the friendly ties which bind Muslims all over the world.

The second came at Lyndhurst in Hampshire, when we delegates from different countries were attending demonstrations of British Guiding, One day, (just after Eid), we were walking across the grass to a Ranger camp, wearing our white and green Guide uniforms, when a young woman dressed English Guide uniform came running quickly towards us.

“Tell me, are you Pakistani Muslims?” she cried,

We answered “yes” and looked at her eager face In surprise.

“I, too, am a Muslim, a Turkish Muslim from Cyprus,” she replied, “and I am here for Guide training. I am so very happy to see you, particularly because you are Muslims like myself. Here I am the only Muslim in the camp. Yesterday was Eid and there was no one with whom to share the happiness of that day.”

We all embraced with enthusiasm and sat down to talk about our respective counties and about Guiding, there. We parted with regret at the end of our stay, but again at Oxford, at the wind-up of our ten days’ Conference, when we had a huge Camp Fire of 10,000 Girl Guides from all over England, there, as all the delegates from the twenty-four countries represented marched slowly across the huge field to their respective places, there in front of everybody, leaning across the ropes, waiting to shake our hands in friendship, was our Turkish friend from Cyprus, Hatlee Tahsin!

From the moment we Pakistani delegates appeared in uniform in English, whether in London of Lyndhurst or Oxford, we attracted attention. People had become used to the dark-blue Guide uniforms of the British, the green of the Americans, the khaki of the Greeks, even to the dark-blue saris of the Indians – but spotless while starched shalwars and qameezes, with folded dark green dupattas and green ties and white shoes, were something quite out of the ordinary. Wherever we went we were surrounded by photographers and Girl Guides, and questioned by people – “How do you keep your uniforms so clean?” “Do you really wear such clothes in your country?” By the time we had been in England for two weeks, wherever we went, whether we were in uniform or wearing silk salwar and qameez or garara, people knew that ours was the dress of Pakistan.

But we found that many people, particularly the Guide delegates from the smaller European countries, still did not know where Pakistan was, and we often had to bring out a map and point out our country to them. We had to answer many questions about our food and general living habits, social customs, education, position of women, the meaning of purdah. People were tremendously interested in us as a country and full of admiration for the progress we had made in the last three years. Many people said that it must be a wonderful experience to be in a new country, where everything has to be built up by one’s own efforts.

GREAT EXPERIENCE

The Conference itself which took place in St Hugh’s College, Oxford, was a great experience. Here in the Conference Hall were hung the flags of the twenty-four nations represented at the Conference, whose delegates, of faiths as divergent as Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Parsee, had met because they were united by a common purpose, viz, to work for the girl and women of the world. Think of the magnitude of the of the movement stated in 1910, which is such that a girl from Pakistan or Egypt can stop a girl who is wearing the Guide badge on the street in America or England, shake her by the hand, call her sister, and at once be friends with her. Our two Pakistani Girl Guides, who had never been abroad before, were received in London with affection and friendship, because they were Girl Guides and they were able to travel on to Switzerland with American, English and Australian Guides whom they had never seen before, but with whom they at once felt at ease.

11 LANGUAGES

In our Conference Hall, women used to chat in eleven different languages, there were women from seven countries who knew more French than English, we had an American Chairman, an English Vice-Chairman, a Belgian translator, and so on, but we were all one. For ten days at Oxford we sat and discussed subjects as diverse as training programmes, camping, finances, public relations, constitution, future policy, – sometimes in English, sometimes in French,- we were entertained in castles and palaces and country homes, we were received in Buckingham Palace by Her Majesty the Queen, we listened to concerts, saw pageants and displays of dancing, and ended a very full fifteen days’ programmes with the gigantic Camp Fire programme at Oxford, on the 29th July, which was attended by 10,000 Guides from all parts of England and which was presided over by Princess Margaret. The Camp Fire was a stupendous sight. An enormous field filled with a sea of faces, all cheering lustily as the delegates from the twenty-four countries marched slowly across the field. Over 10,000girls and women were singing the songs which are known to the two and a half million Guides all over the world, all friendly and united because they were all Guides who had taken the same promised of service to mankind and who all lived recording to the precepts of the ten Guide laws. There they all were – over 10,000 of them, representing the two and a half million Guides in the jungles of Africa, the mountains of Switzerland, the forest of Canada, the Philippine Islands, the plains of Pakistan – Guides from large towns and tiny villages, of different races and creeds and cultures, all different, but nevertheless all one.

Read my piece on the Kartarpur corridor in The Conversation

Three kilometres from the Indian border, in the tranquil green plains of the Narowal district of Punjab in Pakistan is an unassuming sacred shrine: Gurdwara Kartarpur Sahib. It’s the final resting place of Guru Nanak (1469-1539), founder of the Sikh faith.

On the other side of the river Ravi, about a kilometre inside the border in the Gurdaspur district of Punjab in India, is the bustling holy town of Dera Baba Nanak. Here stands Gurdwara Shri Darbar Sahib, associated with the life and family of the same first Sikh guru.

On a clear day, both are visible to each other. But the Radcliffe Line, drawn in August 1947 between Pakistan and India, ensures that travel for the average Indian or Pakistani is impossible across this international border. India’s Sikh community is roughly around 20m people – under 2% of India’s population of over a billion. More than half of them live in the Punjab, India and are cut off from the most significant shrines associated with the founder of their faith, all located in Punjab, Pakistan.

Going through some archival footage from The Pakistan Times I come across this gem from 28 April 1960 in Letters to the editor. Written in 1960 but some of the issues highlighted in the letter still exist even today, especially in the second paragraph. What is also fascinating is how many men were really marrying ‘foreign’ girls during this period? Was it really that prevalent, enough to prompt a letter to the editor? If anyone knows more or knows of such stories please do share these with me.

May I invite your attention to a grave social problem which is becoming more and more acute day by day.

It has been observed that large number of our young men who get an opportunity to go abroad for higher education, professional studies or training come back with foreign wives. This is very frustrating for our own eligible girls. It deprives them of intelligent marriage partners. On the other hand, those who marry these foreign ladies become status conscious and become eager to raise their standards of living. Their wives feel like fish out of water in our society. They cannot freely mix with us due to a great difference in cultural, social and religious background. Naturally, they try to divert their husbands from the country’s social stream. Thus these young men – our own kith and kin – virtually become foreigners in their own milieu. This is no fault of theirs. It is a natural process.

The question is why do these young men marry abroad? The answer is very simple, in our society they have no opportunity to come in contact with girls and hence no understanding can possibly develop between them. It does not need much imagination to foresee the serious consequences of this tendency, which is the product of our defective social pattern and of the ignorance of the parents. If they give their children even a limited opportunity to mix with one another and then chose their life companions our young men will not even dream of marrying aboard, this will make for social integration and give a chance to our girls to contract suitable marriages.

Abu Saeed Ahsan Islahi, Rawalpindi

Abstract:

This article weaves together several unique circumstances that inadvertently created spaces for women to emerge away from the traditional roles of womanhood ascribed to them in Pakistan. It begins by tracing the emergence of the Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) as a national carrier that provided an essential glue to the two wings of Pakistan. Operating in the backdrop of nascent nationhood, the airline opens an opportunity for the new working women in Pakistan. Based on first-hand accounts provided by former female employees, and supplementing it with official documents, newspaper reports and the advertising used for marketing at the time, it seeks to provide an illuminating insight into the early history of women in Pakistan. While the use of women as markers of modernity and propaganda is not new, here within the context of Cold War and American cultural diplomacy, the ‘modernist’ vision of the Ayub-era in Pakistan (1958-69), and its accompanying jet-age provide a unique lens through which to explore the changing role of women. The article showcases a different approach to understanding the so-called ‘golden age’ of Pakistani history: a neglected area of the international history on Pakistan, which is far too often one-dimensional.

Link to the article: https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2018.1472622

In March 2017, in an impromptu adventure, I had the opportunity to visit Kartarpur Sahib in Pakistan. It came amidst an amazing road trip, which took me from the Radcliffe line to the Durand Line (almost). The trip was full of surprises – monuments (old and new) in situ and people on the move – and their discussion, especially of religious spaces and their historical significance. During one of these conversation, Dr. Yaqoob Khan Bangash (ITU Lahore) asked why the Sikhs never demanded Kartarpur Sahib during the discussions of the 1947 Radcliffe Boundary Commission.

Kartarpur is located in Narowal District in Pakistani Punjab. It is about 120 kms/2 hours away from Lahore and is located only 3 kms from the Indo-Pakistan border by the river Ravi. Indeed, Dera Baba Nanak is located about 1 km from the border, on the other side, east of the river Ravi in Indian Punjab. Both are visible to each other on clear days. The Gurdwara is the historic location where Guru Nanak (1469-1539) settled and assembled the Sikh community after his spiritual travels around the world. It is on the banks of the River Ravi and even today there is a nomadic and unkempt, wilderness feel to the place. Guru Nanak spent eighteen years living in Kartarpur, during which he spent time preaching to a growing congregation; the appeal of Nanak spreading from nearby areas to beyond and drawing the first Sangat to the area. Many devotees remained and settled in Kartarpur, dedicating their lives to the mission of Nanak.

The informal led to the formal, with the establishment of the first Gurdwara (the house of the guru) being built circa 1521-2. Here, free communal dinning (langar) was started, feeding all those that came and the langar remains a defining feature of Sikhism – providing free food to everyone without any prejudice. The food is simple and usually vegetarian. It is not a feast, nor does it offend anyone due to their dietary preferences. Everyone, rich or poor, sits together; equal in the house of the guru.

However, for Sikhs, Kartarpur is an especially significant place, as it marks not only the beginnings of Sikhism but also the final resting place of the first guru. The original Gurdwara complex was washed away by floods of the river Ravi and the present-day building was built with donations from Bhupinder Singh (1891-1938), Maharaja of Patiala. More recently, the Government of Pakistan has been contributing to its maintenance. The most fascinating thing about Kartarpur is the appeal of the Gurdwara to all communities. Baba Nanak is revered as a Pir, Guru and Fakir alike.

My trip to Kartarpur was during the “off-season” period and so, mostly Muslims were visiting the shrine/Gurdwara to offer their duas/prayers. Legend has it that when Guru Nanak died, his Hindu and Muslim devotees disagreed about how his last rites should be performed: cremation or burial? During this ruckus, Nanak appeared as an old man before his devotees and, seemingly, suggested delaying the decision until the following day. The following morning, the shroud covering the body was found with flowers, in place of the body. These flowers were divided, with the Hindus cremating theirs, and the Muslims buried theirs. And so, in the courtyard of the Gurdwara is a shrine to symbolise this story. Outside the Sikh tourism that takes place, which is limited, this shrine is mostly frequented by Muslims.

In August 1947, Kartarpur was in Gurdaspur district, which had all (almost) been delineated to be in Pakistan, until the late, controversial changes to the boundary line, which meant that parts of Gurdaspur went to India. Thus, at the last minute, Kartarpur ended being in close proximity of the international border. After Partition, the Sikhs were negligible in their numbers in Pakistan and Kartarpur remained closed and abandoned for over fifty years. More recently, there have been attempts to get a connecting corridor between the communities in India and Pakistan today, but this has not materialised. Going back to the question of why Kartarpur never figured as a specific request before the Boundary Commission, perhaps part of the answer lies in the fact that Sikhs believe in reincarnation of the soul and, therefore, death of the body is not the end of life’s journey.

‘Corridor connecting India with Kartarpur Sahib Shrine in Pakistan ruled out’ by Ravi Dhaliwal:

‘Visit to Kartarpur Sahib (Pakistan)’ by Dalvinder Singh Grewal: https://www.sikhphilosophy.net/threads/visit-to-kartarpur-sahib-pakistan.49707/

‘How Nanak’s Muslim followers in Pakistan never abandoned Kartarpur Sahib, his final resting place’ by Haroon Khalid: https://scroll.in/article/857302/how-nanaks-muslim-followers-in-pakistan-never-abandoned-kartarpur-sahib-his-final-resting-place

Everyone’s Guru by Yaqoob Khan Bangash: http://tns.thenews.com.pk/everyones-guru/#.WxAxiakh3OQ

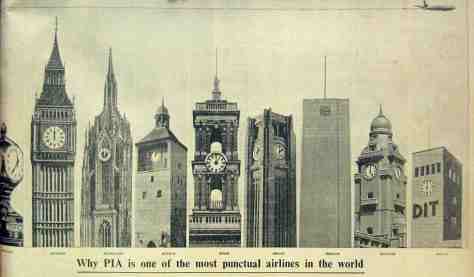

Going through my picture library for images, I found this advertisement by Pakistan International Airlines from 1963. Times have changed.