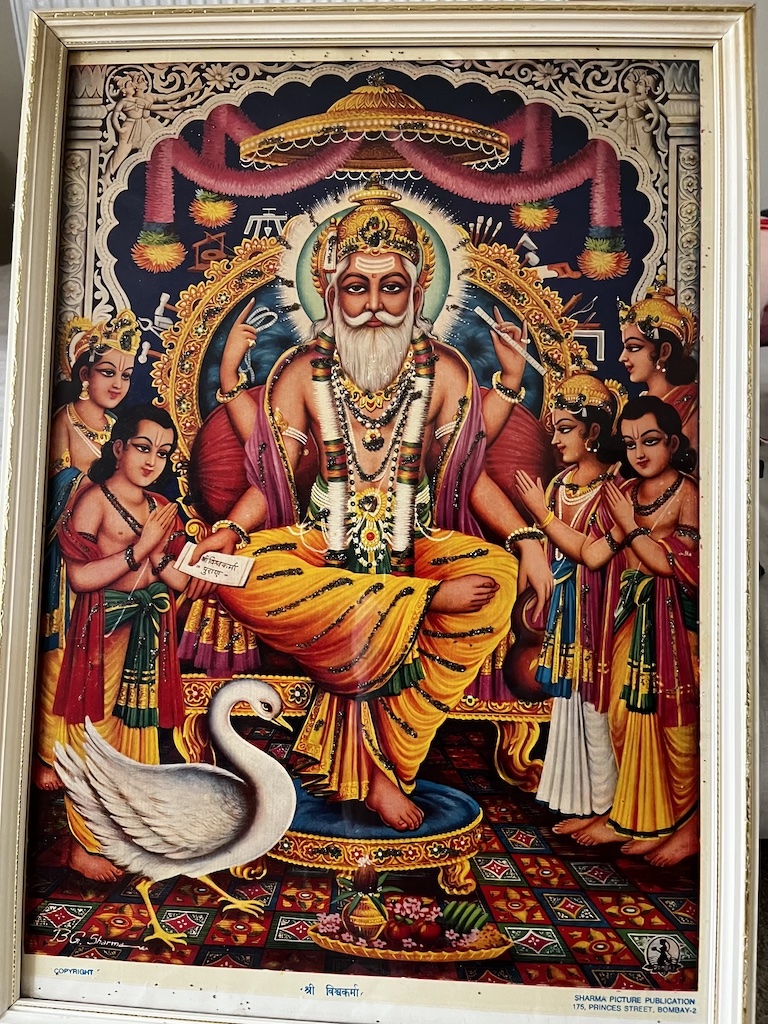

While reading the news from India, the celebrations of Baba Vishwakarma Day caught my imagination. Not least because as I was speaking to my sister earlier on, who had mentioned that the electricity went off due to heavy rains, and the local ‘bijli walla’ won’t come to fix it today. Why I asked? Well because it’s Baba Vishwakarma Day!

The discussion inevitably led us to reminisce about the past and we started talking about Baba Vishwakarma and what it meant to us, especially when growing up. I recall my mother having a photo of Baba Vishwakarma in her prayer room, but the day after Diwali was especially important because this is when we celebrated Vishwakarma Day. She would offer special prayers with prasad (offering) consisting of sweet boondi, that was bought for this purpose. The conversation with my sister prompted me to go and find that picture, which I had kept as a keepsake for many years.

My mother stitched clothes, mostly salwar kameezes, to make ends meet, a talent that she was well-known for in the local community. She was meticulous, everyone who had clothes made by her was aware of her fine cutting and stitching skills, and how well presented her clothes were when she delivered them. I helped when I was able to, but my standards were never high enough! The sewing machine was at the heart of her (our) survival and also how she was able to reinvent herself from a housewife to a single parent with young daughters in a new place.

So why are the Ramgarhia community associated with Vishwakarma? This is because the deity is associated with machinery, technical work, tools and is often described as the God of carpenters, goldsmiths, blacksmiths, and those who work in skilled crafts. The Ramgarhias were originally a community of artisans who worked in these professions, and adapted and upskilled to mechanical work during the 19th century, but the old associations and traditions remain, at least for some.

These stories are now a part of my memory and history, even though the narrative today may be different. My parents belonged to a generation that was more open, less prescriptive and the religious boundaries were more porous. I went to gurdwaras, I took a dip in the Ganges, and we went to Sufi shrines, it was part of the collective identity. Although Punjab witnessed some of the most horrific communal violence in the 1947 Partition, the region is also ironically one of the most pluralistic. For a devout Sikh, my mother was perfectly at ease with the presence of Baba Vishwakarma and indeed Baba Balak Nath in her prayer room, both of whom have a strong presence in Ludhiana amongst the Ramgarhia Sikhs.

So, while doing some research for this post, I came across a PhD from the University of Leeds by Sewa Singh Kalsi (1989). It made interesting reading and I share some key extracts, which provide a glimpse into the history and transformation of the Tarkhan/Ramgarhia Sikhs. Kalsi’s study focused on the city of Leeds (UK) but the extracts below show the emergence and transformation of this small but important community.

“The entry of the Tarkhans into the Sikh Panth can be traced to Bhai Lalo, a carpenter of the village Aimnabad, now in Pakistan. On his first travels (udasi) Guru Nanak stayed with Bhai Lalo where he composed his celebrated hymn enunciating his mission. He addressed this hymn to Bhai Lalo, condemning the mass slaughter by the army of Babur, the first Moghul emperor of India. Commenting on the status of Bhai Lalo within the Sikh Panth, McLeod says that “Even higher in the traditional estimation stands the figure of Bhai Lalo, a carpenter who plays a central part in one of the most popular of all ianam-sakhi (biography) stories about Guru Nanak” (1974:86). Gurdial Singh Reehal in Ramgarhia Itihas (History of the Ramaarhias) (1979) notes the names of seventy two distinguished Punjabi carpenters who worked closely with the Sikh Gurus and made valuable contributions to the development of Sikh tradition. He says that “Bhai Rupa, a prominent Tarkhan Sikh officiated at the wedding of the 10th Guru, Gobind Singh. His descendants known as Bagrian-wale (belonging to the village of Bagrian) were the royal priests of the Sikh rulers of Phulkian states. They administered the royal tilak (coronation ceremony) and officiated on royal weddings” (Reehal 1979:162). It seems plausible that the entry of Tarkhans into the Sikh Panth took place under the leadership of distinguished Tarkhan Sikhs over a long period.” P 104

“Most prominent among the followers of Guru Gobind Singh were two Tarkhan Sikhs, Hardas Singh Bhanwra and his son, Bhagwan Singh, who fought battles under his command. After his death in 1708, both leaders joined forces under Banda Bahadur to lead the Sikh Panth. Commenting on the position of Bhagwan Singh Bhanwra within the Sikh Panth, Gurdial Singh Reehal says that “Bhagwan Singh was appointed governor of Doaba (Jullundar and Hoshiarpur districts) by Banda Singh Bahadur” (1979:209). Jassa Singh Ramgarhia was the eldest son of Bhagwan Singh. He inherited the skills of his father and grandfather and became the leader of Ramgarhia misl (armed band). Jassa Singh built the fort of Ramgarh (this means literally the fort of God) to defend the Golden Temple, Amritsar. McLeod notes that “In 1749, however, he (Jassa Singh) played a critical role in relieving the besieged fort of Ram Rauni outside Amritsar. The fort was subsequently entrusted to his charge, rebuilt and renamed Ramgarh, and it was as governor of the fort that he came to be known as Jassa Singh Ramgarhia” (1974:79). The title of Ramgarhia was bestowed on Jassa Singh by the leaders of the Sikh misls. According to the Dictionary of Punjabi Language (1895), the word “Ramgarrya” means a title of respect applied to a Sikh carpenter. Describing the position held by Jassa Singh among the leaders of Sikh misls, Saberwal in Mobile Men says that “We have noted the part played by Jassa Singh Ramgarhia in the 18th century; though a Tarkhan, by virtue of his military stature he sometimes emerged as a spokesman for all twelve Sikh misls in relation to other centres of power” (1976:99).” P 105

“In order to understand the emergence of Ramgarhia identity, we must locate the processes which have enabled them to move in large numbers from jajmani relationships in the village to urban-industrial entrepreneurship both within India and East Africa. The extension of British rule to the Punjab opened up enormous opportunities for the Punjabi Tarkhans. They channelled their energy and resources into going abroad in search of wealth and towards participating in the urban-industrial growth in India. Their technical skills were harnessed to build railways, canals and administrative towns both in India and East Africa. The Ramgarhias were the majority Sikh group, approximately 90 per cent of the whole Sikh population in East Africa (Bhachu 1985:14; McLeod 1974:87). In East Africa, they established their social and religious institutions like the Ramgarhia associations, Ramgarhia gurdwaras and clubs. By the 1960’s, the Ramgarhias had moved from being skilled artisans, indentured to build the railways, to successful entrepreneurs, middle and high level administrators and technicians. Bhachu argues that “Support structures developed during their stay in East Africa have not only helped manufacture their ‘East Africanness’ but have also aided the perpetuation of their identity as ‘staunch Sikhs’ in the South Asian diaspora, independent of the original country of origin” (1985:13). In East Africa, the Ramgarhias demonstrated a remarkable capacity for maintaining the external symbols of Sikhism, which is a clear indication of their commitment to the Khalsa discipline.” P 107

“The Ramgarhias achieved a noticeable measure of economic success in the urban-industrial sector, both in India and in East Africa. They were able to discard the low status of a village Tarkhan by transforming themselves into wealthy contractors and skilled artisans employed in railway workshops and other industries. In cities they were associated with the Khatri Sikhs, the mercantile group in urban Punjabi society. In the Punjab, the distinctive feature has been the concentration of Ramgarhia Sikhs in particular towns i.e. Phagwara, Kartarpur, Batala, and Goraya. These towns are known for car parts industries, furniture, foundries and agricultural machinery owned by the Ramgarhia Sikhs. This newly achieved economic status was one of the factors which encouraged them to build religious, social and educational institutions belonging to their biradari. In the town of Phagwara, they have built an educational complex which includes a degree college, a teacher training college, a polytechnic, an industrial training institute and several schools.” P 108

And finally, a line from where I take the title of this piece. One of the people interviewed notes: “My spiritual guru is Nanak Dev and my trade guru is Baba Vishvakarma. Many Ramgarhias feel ashamed to be associated with our trade deity.” P 117.

Further references include my own book, in which I discuss the community in relation to the transformation of Ludhiana.

Bhachu, P. (1985). Twice migrants: east African Sikh settlers in Britain (Vol. 31100). Tavistock Publications.

Kalsi, Sewa Singh (1989) The Sikhs and caste : a study of the Sikh community in Leeds and Bradford. PhD thesis, University of Leeds.

Kaur, P. (2017) The dynamics of urbanisation in Ludhiana city. International Journal of Advanced Research and Development, Volume 2; Issue 6, 547-550.

McLeod, W.H. (1974) Ahluwalias and Ramgarhias: Two Sikh castes, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 4:1, 78-90, DOI: 10.1080/00856407408730689

Virdee, P. (2018). From the Ashes of 1947. Cambridge University Press.