When Faiz passed away at the age of 73, Dawn described him as:

The greatest Urdu poet of his time, Faiz became a legend in his lifetime for his intrepid struggle against what he himself once described as “the dark and dastardly superstitions of centuries untold”. He understood the agony of the dispossessed and the disinherited and he sang of them and for them to the last.

While these songs and poems need no introduction, he also wrote enduring prose. On his 35th death anniversary, pasted below are some selections:

‘The Role of the Artist’, Ravi (Lahore) 1982:

‘Who are we – we the writer, poets and artists and what can we contribute, if anything, to avert the moral calamities threatening mankind? We are the offspring, in the direct line of descent of the magicians and the sorcerers and music makers of old…They found for the hopes and fears of their people, for their dreams and longings, words and music that the people could not find for themselves. And by blending their collective will to a desired end, they would sometime make the dream come true…In our part of the world through long centuries…the magician of old became the post-mystic or the mystic poet, the forerunner of the modern humanist, who defied both emperor and priest to articulate the ills and afflictions of his fellow beings, to expose the injustices of their masters and their master’s collaborators, who taught them to believe in, and fight for, justice, beauty, goodness and truth, irrespective of personal loss and gain…So that is who we are, inheritors of this magic…And never was the power of this magic more devoutly to be wished than in the world of today when so many powerful agencies are at work to deny the validity of all ethical human values, to obliterate all refinements of human feeling…by extolling cynicism, insensitivity and brutishness as the hallmark of a he-man and a she-woman…’

Source: Coming Back Home: Selected Articles, Editorials and Interviews of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, compiled by Sheema Majeed, introduction by Khalid Hasan, Karachi: OUP, 2008, pp. 40-1.

‘The Writer’s Choice’:

‘Literature like science is a social activity…Literature unfolds in a similar fashion…the unexplored or dimly lit complexities of social reality, the given human situation of a given time. The impact…however, more insidious, more subtle and at the same time more direct…. The writer is directly manipulative and formative of the consciousness of the audience…He cannot plead, therefore, that he is unaware of, or unconcerned with, social implications…A writer may be tempted, coerced or bribed [by] vested interests to ignore, emasculate, or pervert the basic realities of social existence under various specious pretences, ‘pure’ literature, art for art’s sake, ‘pure’ entertainment etc., a mechanistic repudiation of these ‘purities’, however, poses another danger. In creative writing to ignore the demands and essentials of artistic creation can be inexcusable, although perhaps not as reprehensible, as the moral and social imperatives of reality. It is but another form of escapism…There is still considerable confusion in most African and Asian countries regarding the function of literature, the role of the writer and the modalities of literary expression. This confusion is partly a legacy of the colonial past, partly a recent import as a product of neo-colonialism…Whatever his social status, his intellect and education will automatically place him in the ranks of the elite minority…He will be called upon to make a choice of his audience – to write for his own class or to transcend the class barriers…’

Source: Coming Back Home: Selected Articles, Editorials and Interviews of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, compiled by Sheema Majeed, introduction by Khalid Hasan, Karachi: OUP, 2008, pp. 43-4.

‘Decolonizing Literature’:

‘When the process of colonial occupation got underway in Asia and Africa the literature and languages of the subject peoples were among the first victims of foreign cultural aggression. Its impact hit different communities in different ways depending on their level of social and cultural development, thus confronting each one of them with a different set of dilemmas in their quest for identity after liberation…(1) The study of Asian and African literatures should be incorporated in the relevant schemes of higher learning…Even language teaching in European languages need no longer be confined to European authors. (2) …publication and marketing of important Afro-Asian writings in still the monopoly of a few Western publishing houses…such publications are only marginal to their main business interests…The high cost of Western publications is another inhibiting factor…Efforts are needed for a re-orientation of the publication trade in Asian and African countries. (3) For many Asian and African writers, ‘international recognition’ still means some notice by the Western media. Some of them are thus induced to set their sights while writing on Western rather than their national readership…There are enough nations in Asia and Africa to make any writer ‘international’ without any Western certification…This needs some rectification not only in the outlook of the writer, but also of his readers’.

Source: Coming Back Home: Selected Articles, Editorials and Interviews of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, compiled by Sheema Majeed, introduction by Khalid Hasan, Karachi: OUP, 2008, pp. 49-52.

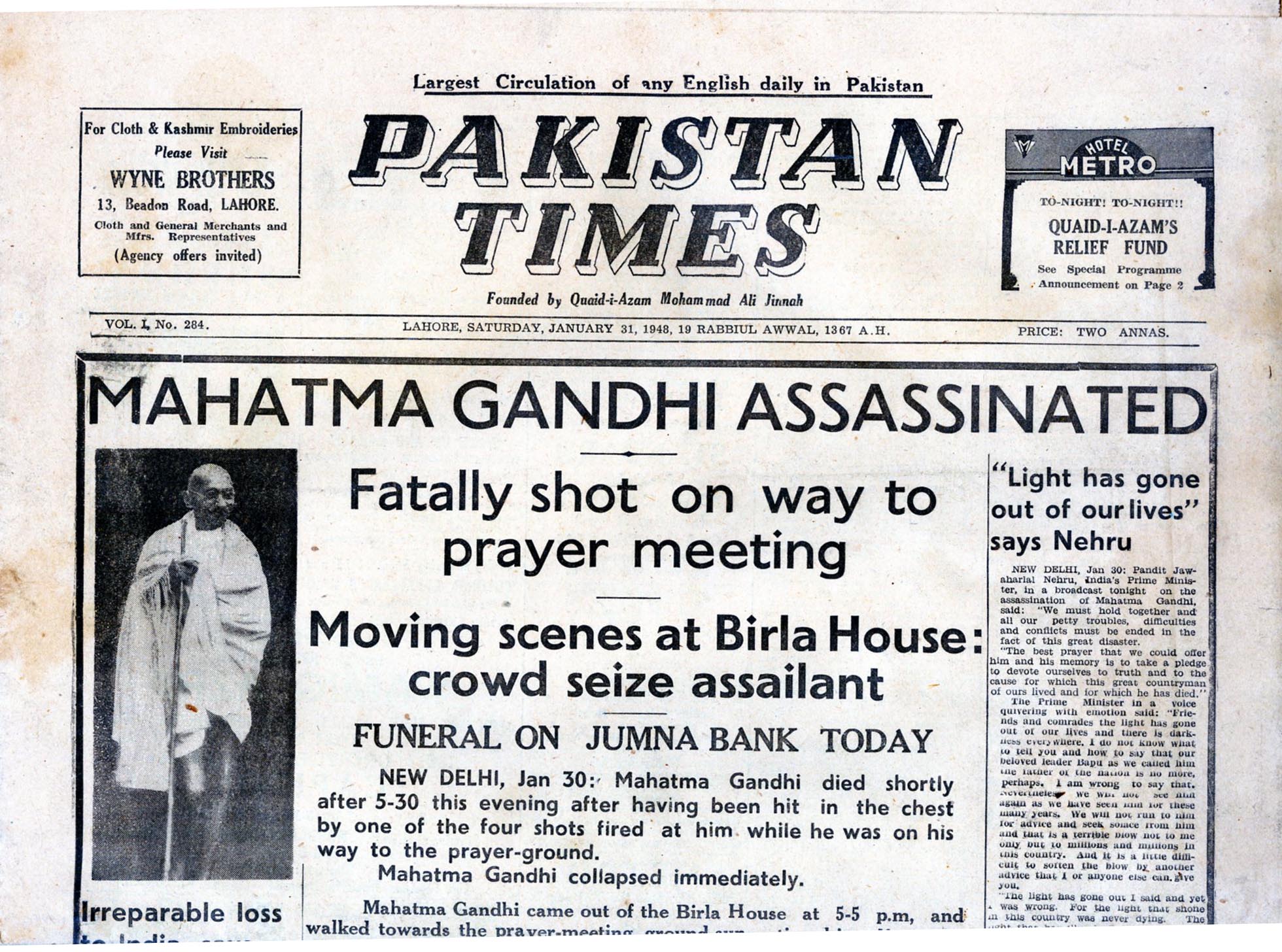

In 1948 Faiz Ahmed Faiz was the editor of The Pakistan Times. Following the assassination of Gandhi on 30 January 1948, he wrote the following editorial. It is a useful reminder of the challenges still facing India today. The RSS was founded in 1925 and banned on 4 February 1948 following Gandhi’s assassination, this remained in place until 11 July 1948. The ban was lifted once the RSS accepted the sanctity of the Constitution of India and respect towards the National Flag of India, both of which had to be explicit in the Constitution of the RSS.

In 1948 Faiz Ahmed Faiz was the editor of The Pakistan Times. Following the assassination of Gandhi on 30 January 1948, he wrote the following editorial. It is a useful reminder of the challenges still facing India today. The RSS was founded in 1925 and banned on 4 February 1948 following Gandhi’s assassination, this remained in place until 11 July 1948. The ban was lifted once the RSS accepted the sanctity of the Constitution of India and respect towards the National Flag of India, both of which had to be explicit in the Constitution of the RSS.