As we approach another year-end in this season of merriment and reflection, and on the shortest day of the year, when daylight is most precious, many of us find time to catch up on projects long left pending. For me, this has meant returning to research into the city of Coventry.

While working on a chapter that uses photographic history to explore migration patterns, I’ve been reading Life and Labour in a 20th Century City: The Experience of Coventry, edited by Bill Lancaster and Tony Mason (1986). The chapter on ‘Migration into Twentieth Century Coventry’ revealed two significant threads: the presence and influence of the Irish Catholic community, and Coventry’s emergence as home to a South Asian community. At the same time, it also revealed the prevalence of racism then, which is comparable to the anxieties that are expressed today. Pages 71-76 are particularly illuminating in linking the political discourse and public fears of the post-war generation to contemporary shifts in British society.

The Myth of 1930s Cosmopolitanism

Coventry in the 1930s was often described as cosmopolitan, but this characterisation was somewhat misleading. Although the population was mixed, with migrants rising to 40% by 1935, most of these newcomers came from other UK regions. This trend continued throughout the war and the immediate post-war period. By 1951, while the overwhelming majority of Coventry’s citizens were of UK origin, some change was also evident.

The Irish Presence

The 9,993 Irish residents counted in the 1951 census marked a significant new wave of migration after the war. Although Irish regiments were often stationed at Coventry barracks and contributed labour during the early 20th century, the local Irish community remained small—only 2,057 in 1931. Nevertheless, this population grew rapidly during the construction boom of the 1930s.

By the end of the Second World War, the streets around St. Osburg’s and St. Mary’s churches had taken on a unique Irish character. These inner-city neighbourhoods, filled with lodging houses and multiple-tenant buildings, and close to Roman Catholic churches, became popular stopping points for itinerant construction workers or individuals looking for factory jobs.

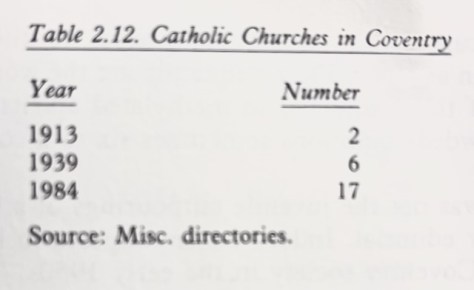

The growth of Catholicism in Coventry during the 20th century reflects both the expansion of the Irish community and their commitment to preserving their religious identity. Interestingly, two current Catholic churches in Coventry cater specifically to European congregations: the Polish and Ukrainian communities.

The South Asian Community and Racial Prejudice

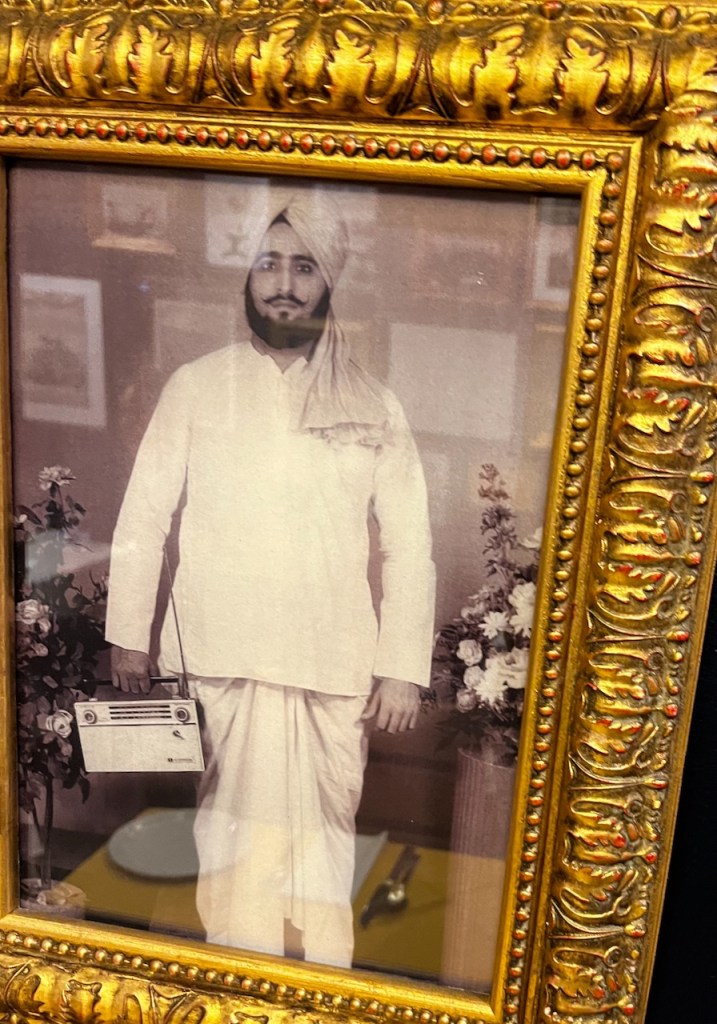

By 1954, the small wartime Indian community had grown to about 4,000 people. Described as a “quiet, peace-loving ethnic minority,” they mainly settled in the older, rundown housing around Foleshill Road. Like many other migrants, they sought to preserve their culture and identity. In October 1952, Muslim members of the community submitted a request to the Planning and Redevelopment Committee for dedicated burial grounds and land to build a mosque.

Although small in numbers, Coventry’s Indian community was nonetheless affected by the growing racial prejudice across Britain. In October 1954, reports emerged that local estate agents were enforcing a colour bar. The week prior, the Coventry Standard published a troubling editorial — not the work of a biased junior reporter, but the newspaper’s primary editorial position:

The presence of so many coloured people in Coventry is becoming a menace. Hundreds of black people are pouring into the larger cities of Britain, including Coventry, and are lowering the standard of life. They live on public assistance and occupy common lodging houses to the detriment of suburban areas. They are frequently the worse for liquor, many of them addicted to methylated spirits, and live in overcrowded conditions, sometimes six to a room.

Lancaster and Mason observe that by the early 1950s, this racism had spread across a wide range of Coventry society. The Standard also reported that a branch of the AEU had contacted Elaine Burton, Labour MP for Coventry South, about the issue. This hostility is particularly notable given that the “coloured minority” made up less than 1.5% of Coventry’s population and, as Stephen Tolliday demonstrates elsewhere in the book, did not threaten the employment of local factory workers.

A City of Newcomers

By 1951, Coventry was mainly a city of recent arrivals, with estimates suggesting that only 30-35% of its population were born there. Many of the newcomers quickly left due to difficulties in finding housing or employment. A study noted that in 1949, 18,000 new residents moved to Coventry, while 17,000 people left.

Moreover, Coventry was hardly a melting pot. In addition to racial prejudice, residents were often unwelcoming to newcomers. Friendships and social networks usually aligned with regional and ethnic backgrounds, with clubs, pubs, and religious groups serving specific migrant communities. Ironically, Coventry’s long-standing identity as a migrant city since the early century may have reinforced the aloofness of the remaining native population – the latter is still palpable in the city’s streets and people.

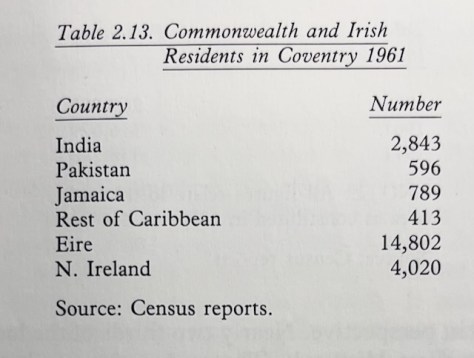

The 1961 census revealed that the 1954 estimate of Asians in Coventry was inflated. New Commonwealth migrants made up only 1.5% of the population, whereas 6.1% was from Eire and Northern Ireland. The flow of migrants from the new Commonwealth was minimal rather than overwhelming. However, between the 1961 census and the so-called mini-census of 1966, significant shifts in migration into Coventry occurred, shifts that would help shape the political rhetoric around immigration for decades to come.

Echoes of the Past

Reading the 1954 Coventry Standard editorial today, with its language about people “pouring in” and becoming a “menace,” makes it impossible not to hear echoes that resonate in British political discourse. Just fourteen years later, on April 20, 1968, Enoch Powell, Conservative MP for Wolverhampton South West, gave his infamous “Rivers of Blood” speech at a meeting of the Conservative Political Centre in Birmingham nearby. Powell heavily relied on letters and anecdotes from the West Midlands, predicting that communities would be “foaming with much blood” because of Commonwealth immigration. His apocalyptic language gained traction in a region that was experiencing real demographic change, even though the scale was often exaggerated by fear and prejudice.

Coventry’s history shows a striking pattern: a persistent disconnect between perception and reality regarding migration. In 1954, ‘coloured’ migrants made up less than 1.5% of Coventry’s population and were described as a menace and a threat to living standards. By 1961, the actual numbers were even lower than the overestimated figures. Despite this, anti-immigrant sentiment gained strength, reaching a peak with Powell’s speech, which appeared to validate fears that years of evidence had shown to be unfounded.

This kind of hostile and often racist political rhetoric continues to thrive today. When Nigel Farage displayed his “Breaking Point” poster in 2016, depicting a line of refugees, or when he claims to feel “like a foreigner in my own country” and warns that migration levels are “unsustainable,” he uses a similar approach: heightening anxiety about cultural change while often distorting the scale and effects. Words such as invasion, being “overwhelmed,” and threats to “our way of life”—these expressions form a continuous thread from that 1954 editorial through Powell to Farage.

Coventry’s historical record is particularly valuable because it allows us to compare predictions with actual outcomes. The threat predicted in 1954 never came true. There was no bloodshed or violence. Despite the panic, racial barriers, and inflammatory editorials, and despite migrants constituting less than 1.5% of the population, Coventry’s diverse communities—Irish, South Asian, Polish, Ukrainian, and others—became an integral part of the city. They did not pose the threats to jobs or living standards that were claimed. Indeed, the post-war boom would not have been possible without this labour migration into the city.

Coventry’s history shows that demographic change is neither easy nor without real challenges. However, the most provocative rhetoric often surfaces during times of economic uncertainty. The true story of Coventry, a city that has been profoundly shaped by migration as it continues to evolve and develop.

As we enter the new year, with migration remaining one of the most contentious political issues in Britain, Coventry’s history offers a lesson worth heeding: our fears of newcomers have consistently proved more destructive than the newcomers themselves. How can we learn from the past without repeating the same anxieties and prejudices?

References:

Ewart, H. (2011). “Coventry Irish”: Community, Class, Culture and Narrative in the Formation of a Migrant Identity, 1940–1970. Midland History, 36(2), 225–244.

Lancaster, Bill and Mason, Tony (eds), Life and Labour in a Twentieth Century City: The Experience of Coventry. Coventry: Cryfield Press, 1986.

Virdee, Pippa. Coming to Coventry: Stories from the South Asian Pioneers. The Herbert, 2006.

Leave a comment