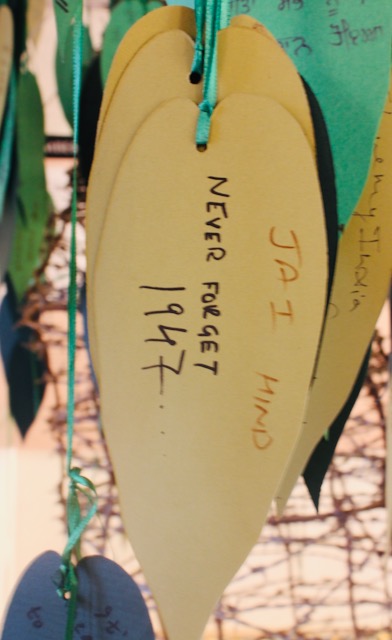

In 2001, I crossed the Wagah-Attari border for the first time. Since then, I have used this official land crossing between India and Pakistan numerous times, in the process seeing the border undergo multiple changes. It used to be the Grand Trunk Road split in half, with a few meters of “no man’s land” to separate them. I could literally walk from one side to the other, while remaining on the GT Road. Then, the authorities decided to uplift, gentrify, and replace the colonial bungalows. Gone was the quaint and informal space with scattered flower beds and plants and in came the flashy buildings, followed by the airport style security, customs, and immigration; culminating eventually in the hideous and expensive battle for who can hoist the largest flag and keep it flying high!

To be fair, the development of the check post at Wagah-Attari was probably a response to the expectation that relations between the two countries would improve, and with that the foot traffic would increase. The bungalows were not equipped to deal with high volumes of people. Hence, they first established the goods/transit depot on one side of the border, so as to divert the trucks carrying the items of import/export. This separated the trade traffic from the people traffic. Whilst the establishment of a goods depot offered signs of improved trade between the two countries, even this was subject to cordial relations.

With numerous crossings since then, I have seen the border change, not just physically but also its ambience and vibes that the place gives. Indeed, the new buildings and transit buses which take passengers from one side to other have functioned to create further distance between the lines of control. These were not there previously, and the cool formality evokes the illusion of being remote and separate. Borders do not have to be harsh and austere.

These moments and emotions are difficult to capture on camera, but they can be felt when encountering the staff and officials. When I first crossed the border, I had the compact Canon Sure Shot AF-7, which was a popular model in the 1990s and gifted to me. I enjoyed taking photographs, but cameras were not cheap then, and the 35mm film was expensive too, both to buy and to develop, so photos were taken sparingly. When I embarked on my doctoral research, taking my camera was essential for my trips to India and Pakistan, as it was an instrument to visually document my journey. I would normally pack 1-3 rolls of ISO 200 (sometimes also ISO 400) speed film, usually 36 EXP, good for general photographs. But one was never entirely sure until the film was taken back home, handed in for developing, which then produced the joy of physically going through the photographs a week later! Time had passed between undergoing the actual trip and now feeling those photographs in my hands, and the images allowed me to recreate and relive those moments again.

Today everything is instant. In a moment I can be taking a photograph at the border, and then share it with the wider public around the world via social media. The only caveat here is that, generally the phone signals are non-existent within 1-2 kilometres of the border area, so you would probably need to wait until you were able to pick up the phone signal. More importantly, this also disrupted any arrangements one had made to meet people on the other side. If I was crossing the border, I might contact my friends/family beforehand and say, I’m crossing at X time (keeping in mind the 30 minutes times difference between the two countries), so I estimate that I will be out at Y time (usually 60 minutes from one side to the other). But if things didn’t go to plan, there is no way of contacting the person to alert them of the delays. And when you did finally make it to the other side, there were always a small number of people anxiously waiting and looking to see when their friends/family will pass through those doors.

There are many other stories of this rather strange and intriguing no man’s land but to end with a more positive story, I share a picture of a dhaba at Attari, Mittra da dhaba (literal translation – friends’ roadside restaurant) is located close to the entrance to check post, catering to travellers and tourists who come for the daily lowering of the flag ceremony. I have gone there many times, but on one occasion in 2017, I asked the owner to pack some food for me, food which I planned to take across the border and share with my friends in Lahore. He took great care to make it extra special and pack the food tightly, so that it wouldn’t spill. I could see that it also brought him great joy to know that his food would travel to the other side. As we parted, he said come back and tell me if they enjoyed it!

Alas, these stories are in the past tense, and with Covid the border faced further restrictions and closures. I have no idea if my friend is still there, I hope so. We need more friends in these otherwise hostile spaces.