Recalling trips to Punjab are akin to a trip down memory lane, one which is not merely nostalgic but aromatically so, from straying into family kitchens and stopping at road-side dhabas, especially along the great GT Road. The latter used to be a family space too, i.e., often family-run businesses, little more than fragrant kiosks under corrugated roofs and rather full of the ubiquitous truck drivers transporting goods along this artery of north-east India. Perhaps my earliest memory is stopping at one such a stall in 1989, maybe mid-way between Delhi and Ludhiana. It was my first visit home since being taken to settle down in Nakuru, Kenya in 1977 and thereafter Coventry, England in 1982.

As we alighted from my brother-in-law’s eponymous Maruti, he had driven to the Palam airport to receive my mother and me, I realised that this was a familiar, if not favourite, spot of his; a feature of this road and its foodie milestones for its regular customers. It was the month of August and even as we sat outdoors, the canopy shaded us from the humid sun, on a traditional, slightly saggy manja/charpai, made of wooden posts and cotton rope. Back then dhabas dealt in a few but firm staples, serving either veg or non-veg – a term perhaps peculiar to the subcontinent – and this one gave primacy to the vegetarian fare. We stuck to the most popular of these: dal makhani (usually made with urad/black dal), served with copious amounts of makhan/butter and hot rotis. Accompanying this were a few condiments like pyaz/onions, pickles, dahi/yogurt, and to wash it all down was lassi/yogurt drink or karak cha/masala tea, notably to keep the driver going for the remainder of the journey.

Where there is food, there should be flies, especially in the open air of Naipaulian post-monsoon north India and, as a teenager coming from England, a major part of my memory is the visual fragment of blowing away flies, alternating with every other mouthful! Nothing – and no one (!) – had prepared me for their insolent onslaught. But the lingering after-taste of the dal with its distinctly earthy, buttery-ness has remained with me, as has the breezy, people-watching – or, staring-Indian-style – feeling of watching the traffic and people go by. Chatting, eating, and enjoying the essence of being back home.

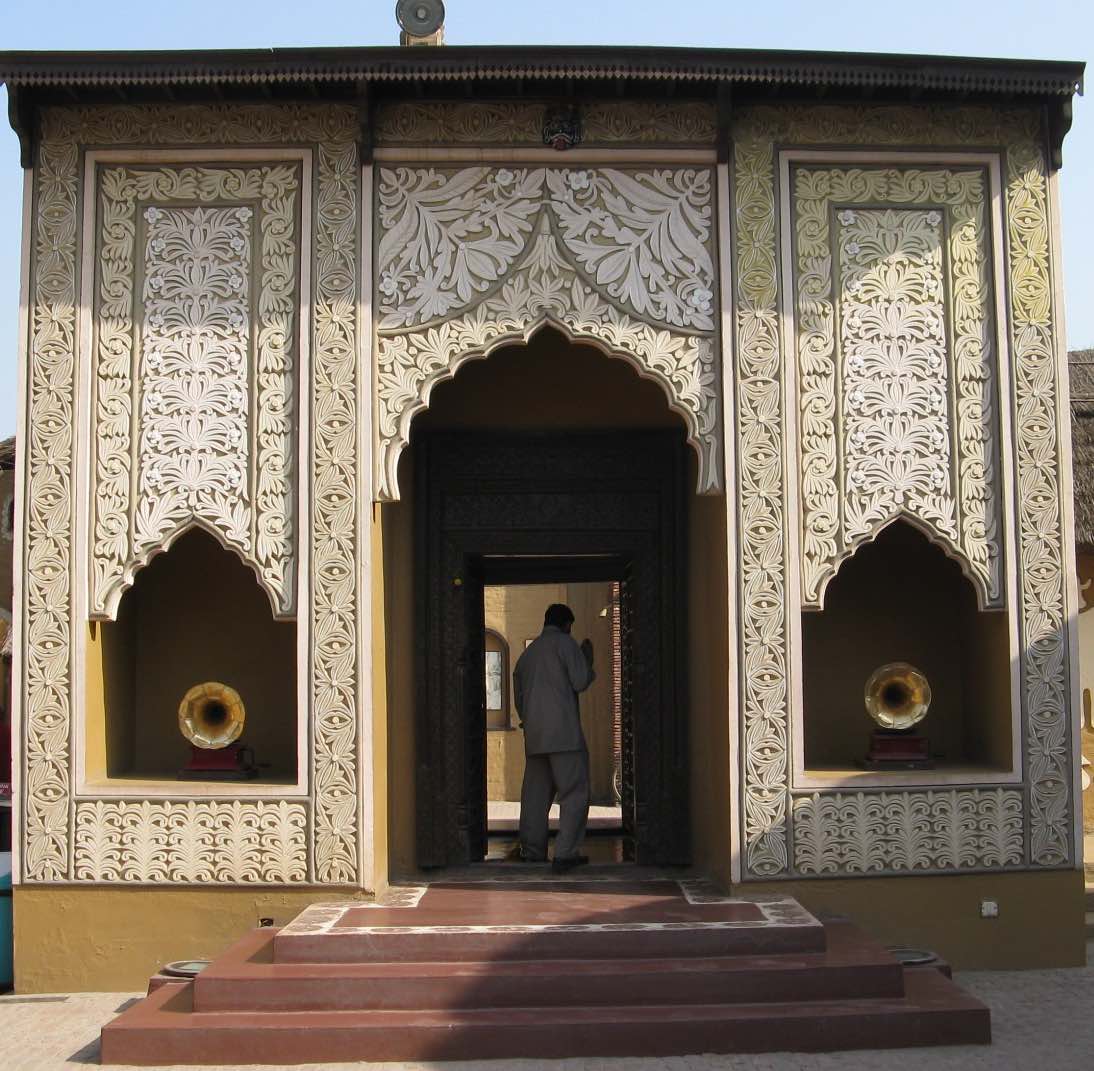

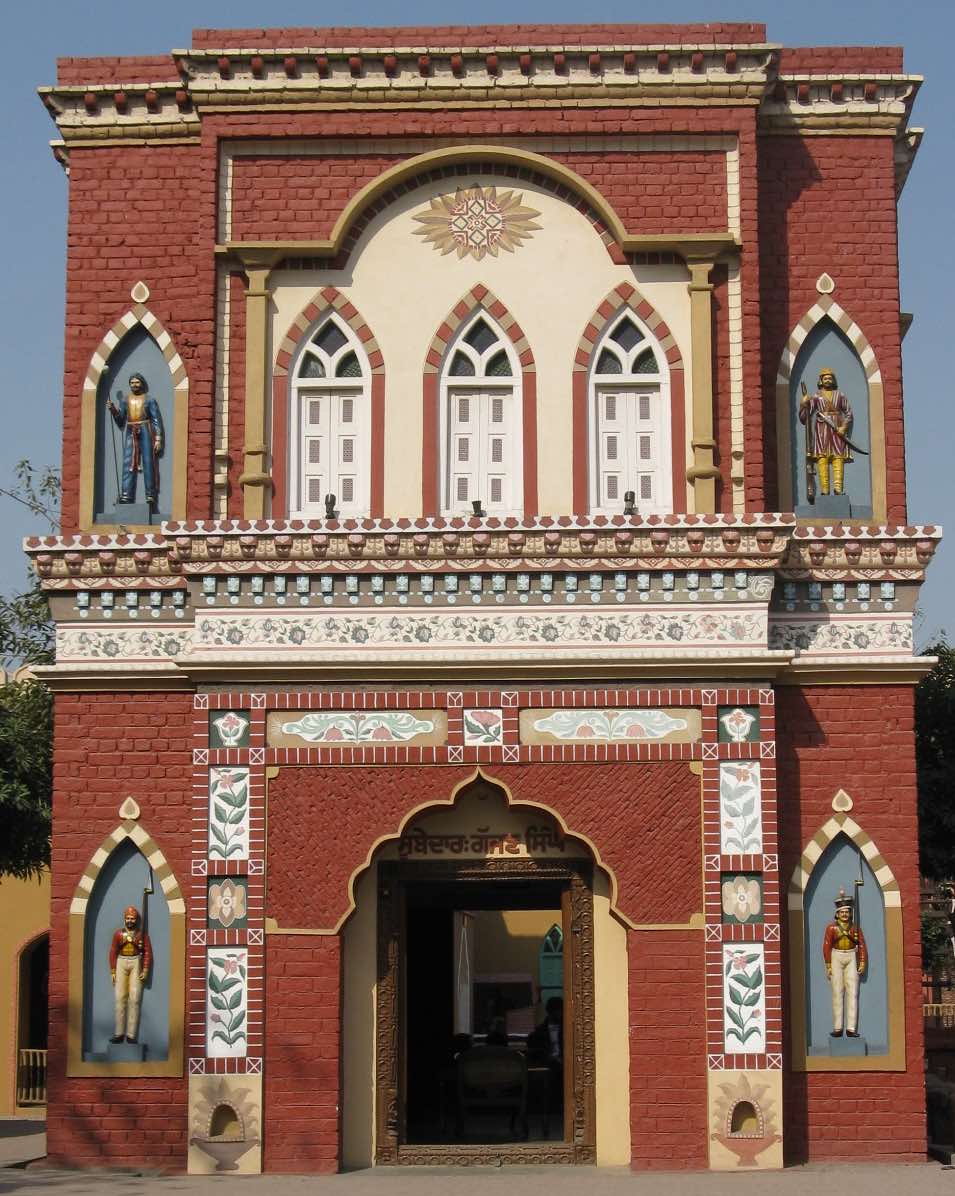

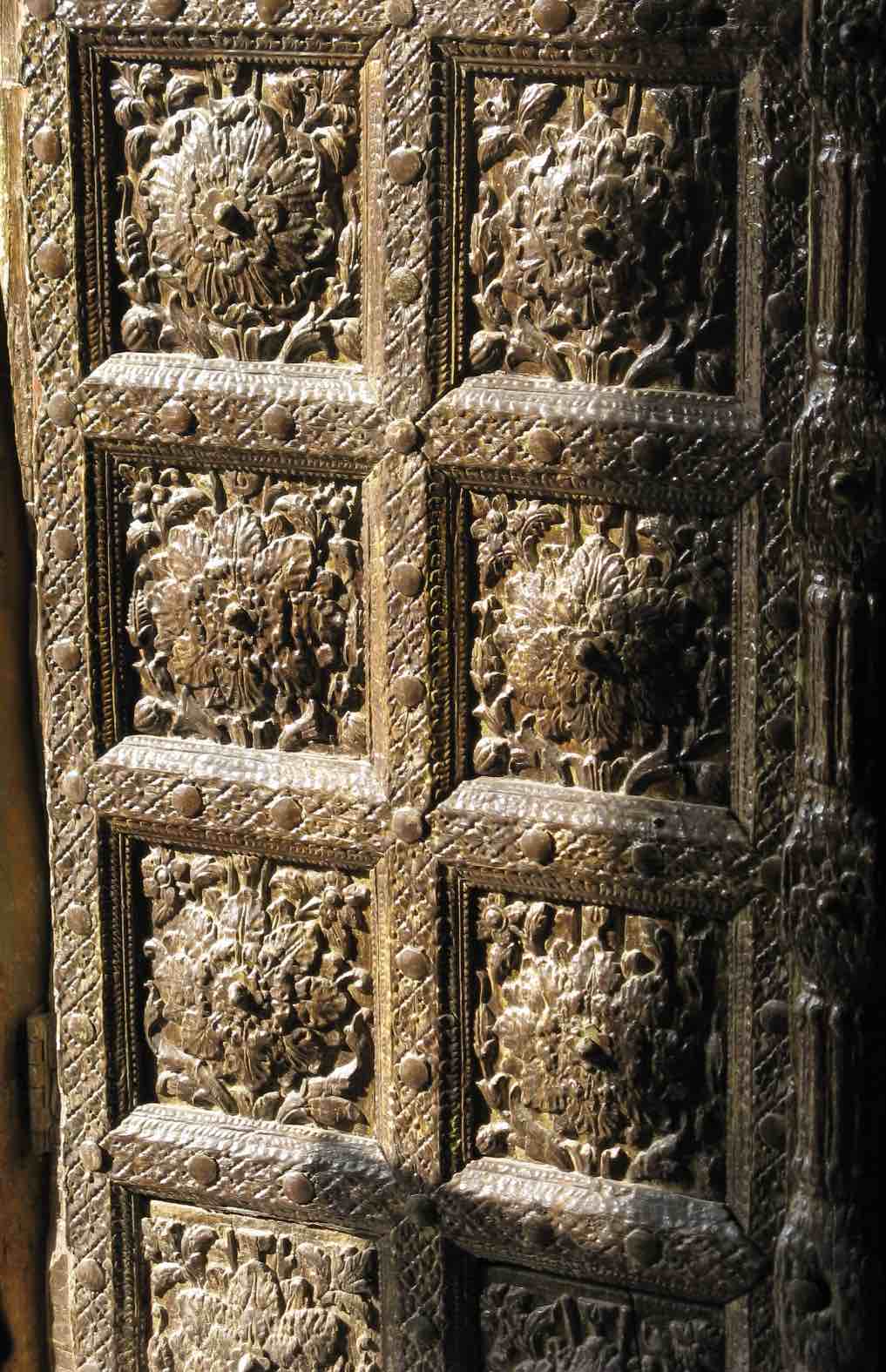

The dhabas not just remain but have metamorphosed into big, loud, air-conditioned restaurants, while being family-friendly; a constant in that ever-changing part of the world. Increasing purchasing power for more in these two-three decades has led to an upward curve in people’s expectations and demands. One of the earliest to step up to (offer) the plate was Haveli, Jalandhar. Its success has led to a number of other branches opening elsewhere, not to mention the imitators and followers. Twenty years after I had first stopped at a dhaba, I first visited the Haveli with my sister, in 2009. I had heard so much about the place in previous conversations. Haveli did not simply serve “traditional” food, it sought to create an “experience” of that traditional age, catering to the wealthy diaspora, who tried hard to reconnect with their roots. Now, therefore nostalgia came at a high price, amidst the sights of a pre-fabricated “themed” restaurant, and accompanied with the Rangla Punjab model village (pictures below from 2009), depicting “typical” village life.