On a recent trip to Lagos, Portugal, I was struck by the presence of Indians, particularly young students, some were perhaps tourists and migrants who appeared to be seeking opportunities, others looked more settled and part of the local community.

The Indian diaspora in Portugal is diverse and can be broadly divided into three distinct regional groups:

- Gujaratis – The largest group, encompassing both Hindus and Muslims, reflects the deep-rooted trade and migration links between Gujarat and Portugal.

- Goans – Predominantly Christian, this group traces its heritage to Portugal’s colonial past, when Goa was under Portuguese rule for over four centuries. This historical connection has shaped their language, culture, and religious practices.

- Punjabis – Predominantly Sikhs, this community has migrated more recently, seeking opportunities in industries like hospitality and retail.

While walking around the streets of Lagos came alive with a rich tapestry of languages, including Gujarati, Punjabi, Hindi, Portuguese, and English, mingling seamlessly. This linguistic and cultural interplay highlighted the adaptability and integration of these communities within the Portuguese society.

Historical Roots and Migration Patterns

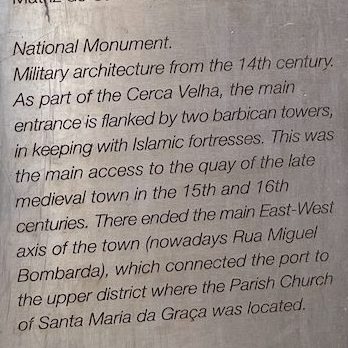

Historically, Portugal’s connection to India dates to the early 16th century when Vasco da Gama’s expeditions established trade and colonial links. [Read Lagos to Goa Part 1] Goa became a Portuguese territory in 1510, fostering a flow of people, goods, and cultural exchange between the two regions. Even after Goa’s annexation by India in 1961, ties between the two nations have persisted, enabling migration and cross-cultural connections.

Kristina Myrvold notes that significant Indian migration to Portugal began in the 1970s after the collapse of the Portuguese Empire and the 1974 democratic revolution. During this period, many Portuguese-speaking Hindus and Christians from former colonies like Mozambique and Goa migrated to Portugal. Later, in the 1990s, Portugal’s entry into the European Union and Schengen Zone made it an attractive destination for immigrants from India, including those with no prior cultural or linguistic ties to the country.

The Growing Sikh Community

Among the broader Indian diaspora, the growing number of Punjabi Sikhs particularly stood out during my visit. Many Indian restaurants appeared to be run by Sikhs, though ownership could belong to others. Myrvold explains that Sikh migration to Portugal began in the early 1990s, coinciding with a construction boom that created a high demand for labour. Many Sikhs initially worked in construction and agriculture, industries that required significant manpower. Over time, they expanded into other sectors, opening shops and restaurants, particularly in hospitality and retail.

Portugal’s relatively relaxed immigration policies and labour shortages during that period encouraged migration. Many Sikhs used Portugal as a stepping stone to secure residency or citizenship, drawn by the affordable cost of living and accessible legal pathways. This trend has driven the growth of the Sikh community in Portugal, which was estimated at 5,000 in 2007 and doubled to 10,000 by 2010. By 2024, the Indian Embassy in Portugal estimated the Sikh population at 35,000, highlighting their increasing settlement in the country.

Settlement and Challenges

Many Sikhs initially arrived in Portugal via other European countries, attracted by Portugal’s relatively lower cost of living and accessible legal pathways to residency and citizenship. Geographically, the Sikh community is spread across Portugal, with significant populations in major cities such as Lisbon and Porto, as well as in Albufeira and other towns along the Algarve. These regions have not only offered economic opportunities but also served as hubs for community life, where Sikhs have built places of worship, such as gurdwaras, and organized cultural events to preserve their traditions and strengthen community bonds.

The Sikhs community in Portugal is relatively new compared to other Indian groups with longer-established connections with the country. While travelling from Lagos to Faro, I had the chance to speak with a Sikh taxi driver who had been living in Albufeira for over 10 years. Despite the initial linguistic and cultural challenges, according to the taxi driver, the quality of life is much better in Portugal. They maintain their links with family back home in Jullundur but work and home is here.

The work is also seasonal and dependent on tourism, the summer being peak time to work long hours and earn double or triple the earnings to compensate for the winter periods when tourism drops. Looking into the future with rising living costs and increasing restrictions on settlement according to the taxi driver, it will make be harder for future migrants to establish themselves in Portugal.

Sources

Kristina Myrvold, ‘Sikhs in Portugal’ Religious Studies Commentaries, 11 August 2012. https://religionsvetenskapligakommentarer.blogspot.com/2012/08/sikherna-i-portugal.html

Inês Lourenco, From Goans to Gujaratis : a study of the Indian community in Portugal, Migration Policy Centre, CARIM-India Research Report, 2013/01 – https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/29463

Jennifer McGarrigle, and Eduardo Ascensão. “Emplaced mobilities: Lisbon as a translocality in the migration journeys of Punjabi Sikhs to Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44, no. 5 (2018): 809-828.

Pamila Gupta, “The disquieting of history: Portuguese (De) Colonization and Goan migration in the Indian Ocean.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 44, no. 1 (2009): 19-47.