It was the winter solstice recently, the shortest day of the year. I find these short winter days difficult, with tiredness and an inability to function beyond sunset. To escape the grey, dull, and wet winters that dominates England now, like many others there, I too like to escape to more sunny pastures.

As I hadn’t been to the Algarve previously, I found the most exquisite guest house, decorated in a North African Arabic style. For many centuries, this “region was ruled by Arabic-speaking Muslims known as Moors. In the 8th c., Muslims sailed from North Africa and took control of what is now Portugal and Spain. Known in Arabic as Al-Andalus, the region joined the expanding Umayyad Empire and prospered under Muslim rule.”

“In 1249, King Afonso III of Portugal captured Faro, the last Muslim stronghold in Algarve. Most Muslims there were killed, fled to territory controlled by Muslims, or converted to Christianity, but a small minority were allowed to stay in segregated neighbourhoods.” In 1496, King Manuel I expelled all Jews and Muslims, turning the kingdom exclusively Christian.

Lagos: From Capital to Catastrophe

(C) Pippa Virdee 2024

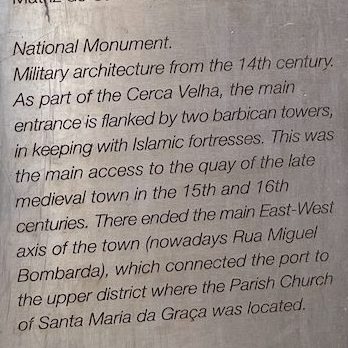

Between 1576 and 1755, Lagos served as the capital of the Algarve region, a time when it stood as a bustling Portuguese city. Unfortunately, the devastating earthquake of 1755, followed by a tsunami, brought widespread destruction, reshaping the city’s character. Today, only fragments of the 16th c. walls and structures remain, such as the Governor’s Castle (Castelo dos Governadores), offering a glimpse into its illustrious past. Much of the Lagos we see today, with its charming streets and architecture, dates from the 17th c. and later, reflecting its rebirth after the calamity.

The Age of Discovery: Lagos’ Golden Era

The history of Lagos is intertwined with one of Portugal’s most celebrated periods, the so-called “Age of Discovery”. During the 15th c., under the direction of Infante Henry the Navigator—the third son of King John I—Lagos became the hub of Portuguese exploration. From this strategic coastal city, expeditions were launched to Morocco and the western coast of Africa, setting the stage for a new era of global trade and navigation. The harbour bustled with activity, as shipbuilders crafted caravels—sleek, fast ships ideal for exploration—and sailors prepared to navigate uncharted waters.

Lagos and the European Slave Trade

While the Age of Discovery brought economic prosperity and technological advancements, it also marked a darker chapter in history. Lagos became a central hub for the European slave trade. In 1444, the first African slaves arrived in Lagos, sparking a grim trade that would expand throughout Europe and beyond. The Mercado de Escravos (Slave Market), now a museum, stands as a sobering reminder of this era, preserving the memory of those who suffered under the system of slavery. Beyond the slave trade, Lagos thrived as a centre for goods such as spices, textiles, and gold, turning it into a key player in Europe’s burgeoning global economy. The city’s rich maritime heritage is still celebrated today. Monuments, such as the striking statue of Infante Henry, honour Lagos’ historical significance, while museums delve into its role in the expansion of Portugal’s empire.

Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese Monopoly on the Indian Ocean

The voyages of Vasco da Gama marked a defining moment in global exploration and trade. His expeditions (1497–99, 1502–03, and 1524) were the first to successfully connect Europe with Asia via the Cape of Good Hope. This cemented Portugal’s dominance in maritime exploration and also laid the foundation for a century-long monopoly in the Indian Ocean.

In 1497, Vasco da Gama set sail from Lisbon with a fleet of four ships through the Atlantic Ocean to reach the Indian subcontinent in 1498. His arrival in Calicut (Kozhikode) marked the beginning of direct European trade with Asia, giving Portugal access to highly sought-after goods like spices, textiles, and precious stones. This sea route transformed global trade, while boosting Portugal’s economy and influence.

The success of Vasco da Gama’s voyages encouraged further Portuguese expansion into Asia, with trading posts and colonies established along the coasts of Africa, the Middle East, and India. By 1500, Portugal had become a maritime powerhouse, dominating European trade in the Indian Ocean and establishing itself as a global empire.

The Strategic Importance of Goa

While Portuguese explorers visited various parts of India, it was Goa that became the jewel in their colonial crown. Acquired in 1510 by Afonso de Albuquerque, Goa offered a strategically defensible location and excellent harbour facilities on both sides of the island. Its position on the west coast of India allowed the Portuguese to control maritime trade routes and establish a stronghold for further expansion into Asia. Goa quickly grew into a bustling hub of commerce, blending Portuguese and Indian cultures.

The Portuguese monopoly in the Indian Ocean lasted until the late-16th c., when other European powers like the Dutch and the English began challenging their dominance. However, the impact of Vasco da Gama’s voyages and the establishment of Portuguese colonies in Asia cannot be understated. These ventures not only reshaped global trade but also led to a lasting exchange of cultures, technologies, and ideas.

Afonso de Albuquerque’s Vision for Goa

When Afonso de Albuquerque captured Goa, he envisioned it not as a mere fortified trading station, but as a full-fledged colony and naval base. Unlike the temporary establishments the Portuguese had built along other Indian coastal cities, Goa was meant to be permanent. Albuquerque encouraged his men to integrate with the local population, fostering intermarriage with local women and encouraging settlement. This strategy was instrumental in creating a privileged Eurasian class, whose descendants formed the backbone of Goa’s colonial society.

Goa quickly grew into a flourishing hybrid settlement, a hub for trade, agriculture, and artisanship, with the influence of the Roman Catholic Church introducing a new dimension to the region. Old Goa, often called the “Rome of the East,” was adorned with magnificent churches, including the Basilica of Bom Jesus and Se Cathedral, reflecting the grandeur of Portuguese architecture.

The Decline of Portuguese Rule

By the mid-20th c., the Portuguese control over India was becoming increasingly untenable. While British rule ended in 1947 and French territories were gradually integrated into India by 1954, Portugal resisted relinquishing its hold. Tensions escalated as Indian nationalists campaigned for the incorporation of Goa and other territories. In 1961, the situation came to a head.

Dadra and Nagar Haveli had already been absorbed into India by August of that year, and on December 19, Indian forces launched “Operation Vijay,” a military invasion of Goa. The operation swiftly ended Portuguese rule, and Goa, along with Damão and Diu, was incorporated into the Republic of India. The fall of Goa marked the end of nearly 450 years of Portuguese presence in India.

Watch this video by BBC News India with accounts of those who fought for independence from Portugal.

A Lasting Legacy

Despite the end of colonial rule, Portugal’s influence remains deeply ingrained in Goan culture. Four and a half centuries of intermarriage, religious conversion, and linguistic exchange created a distinct identity. Catholicism continues to be a major religion in Goa, and the Konkani language still carries traces of Portuguese vocabulary. The architecture of Old Goa, with its grand churches and baroque facades, stands as a testament to this shared history.

The cultural legacy of Portuguese rule can also be seen in Goan cuisine, music, and festivals, which blend Indian and European traditions in a way that is uniquely Goan. From the spicy vindaloo curry to the lively strains of fado music, the echoes of Portugal are impossible to miss. Ironically both Lagos and Goa are today known more as tourist destinations with their bustling beaches and vibrant nightlife; their connected past remains in fragments, scattered and visible to those who seek.

To follow…Notes from Lagos (Portugal): from Punjab to Lagos (Part 2)