Hector Bolitho’s Jinnah: Creator of Pakistan is how it ended, in 1954; below is how it started, in 1951-2:

Hotel Metropole (Karachi), 4 February 1952, Bolitho to S.M. Ikram (Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of Pakistan)

‘I have just returned from a conversation with Miss Jinnah [who had ‘issued a statement that she neither knew about, nor had anything to do with, Bolitho’s assignment’] and I feel that time has come for us to review the circumstances in which I have attempted to write the official biography of Quaid-i-Azam.

I have now been in Pakistan for almost one month [government had to issue a press note explaining the decision to engage ‘a foreigner’, in response to ‘a section of Pakistan Press’ raising a controversy], and I feel that, in the present circumstances, it would be dishonest and impossible for me to write a biography that would be worthy of the subject or acceptable to any reputable firm of publishers.

Since I have been engaged on my task, which began on October 22nd [the cabinet of Liaquat Ali Khan had approved minister I.H. Qureshi’s proposal to commission Bolitho on June 20, 1951], I have been refused all help from those officials who knew Quaid-i-Azam personally. K.H. Khurshid, his secretary, now in London, has expressed his regrets that he will not help. M.H. Saiyid, sent to me by you, has also refused to co-operate.

[Khurshid would later publish his Memories of Jinnah (1990, 2001). Saiyid would also publish A Political Study of Jinnah (1953, 1962), titled The Sound of Fury (1981)]

Mazhar Ahmad, A.D.C. to the Quaid, whom you promised as my helper, has not been made available. Prof. Mahmud Brelvi [?], appointed to help me, has not appeared for six days. Although he has been scrupulous in his courtesy, your office has ignored my situation, and has offered no explanation of Prof. Brelvi’s withdrawal. Nor has anyone been deputed to take his place. Nor, in this past month, have I been given even one of the promised documents relating to the Quaid. Nor has Miss Jinnah been approached by the Government. I have taken legal advice, and I find that Miss Jinnah owns the copyright of all her brother’s documents. She has stated to me that these are being used for the biography on which she is now engaged [Ghazanfar Ali Khan (then Pakistan’s Ambassador in Iran) had given a statement ‘welcoming Miss Jinnah’s decision’, adding that ‘she “should have been the first person to be consulted by the Government”’. I.H. Qureshi had been ‘seeking the assistance of his colleagues acquainted with Miss Jinnah to approach her, but these efforts failed’. Her book My Brother (1955) came out in 1987.]

As an indication of the frustration and discouragement I have endured from your department, I would draw your attention to my letter of January 19th. There I mentioned the Aga Khan’s offer to help me. His collaboration would be almost as valuable as that of Miss Jinnah. Sixteen days have passed since I wrote this, without the courtesy of a reply from you.

All this suggests that the Government is apparently unable, or unwilling, to abide by our contract. I consider that I have been deceived in this matter of documents, and the promised help of “members of the family” of the Quaid. I am wondering, therefore, if it would not be best for us to terminate our contract, under terms which I shall made as reasonable as possible. I propose:

- That the sum of [2000] guineas – the remainder of my fee – be immediately paid into the office of my solicitors in London (Messrs Shirley Woolmer & Co.) with instructions to them to hold the money until the contract between us is formally cancelled.

- That, as compensation for the loss of income from the sales of the English-language book rights in England, America, and the Sub-continent, I be compensated to the extent of [5000] guineas.

- According to my contract, I am entitled to hotel accommodation for myself and [researcher] Captain Peel for [4] months. As my house in London is let, I shall require hotel accommodation for myself, and I shall have to compensate Captain Peel, until June 2nd. I therefore propose that the Pakistan Government pay me the sum of GBP 80 per week (based on last week’s bill) from the date of my leaving Pakistan until the period of [4] months is up.

- All sum to be free from any deductions of income tax or other dues, and paid in full in London.

- That 1st-class sea passage, to be approved by me, for myself and Captain Peel, be provided, as soon as possible, to England.

I am anxious to conclude this matter as soon as possible, because it is desirable for both of us that the story should not become distorted in the world press. I have already been approached to make a statement to a New York newspaper, and to an Indian newspaper.

I have no wish to see the Government embarrassed, and I am sure that we could come to an arrangement. I ask only for speed. Although our agreement was made in London, and, therefore, any legal action would no doubt have to be taken there, I trust that we can close the matter amicably, thus avoiding publicity unpalatable.

[The agreement text spoke of ‘not less than 90, 000 words’ biography for ‘the fee’ of 1000 GBP ‘on the signing of this contract’, 1000 GBP ‘on delivery of the finished manuscript to the publisher’ and, 1000 GBP ‘on publication in England or America (whichever first) + 1st class return sea passages, rail fares, travelling facilities and hotel accommodation for a period of 4 months, a liaison officer and all ‘reasonable assistance and facilities for the purpose of obtaining information, examining documents and interviewing government officials and members of the family’]

A disgruntled Bolitho, before writing the above letter, gave an interview to the Sind Observer, without warning to the government, published on 29 January 1952, in which he ‘hinted at the possibility of his giving up the assignment and seeking compensation because he had put all his work aside to fulfil this request which came first from Liaquat Ali Khan’.

Source: File No. 3 (6) – PMS/52 (Government of Pakistan, Prime Minister’s Secretariat)

What happened in-between, recalled In Quest of Jinnah: Diary, Notes and Correspondence of Hector Bolitho, edited by Sharif al Mujahid, 2007.

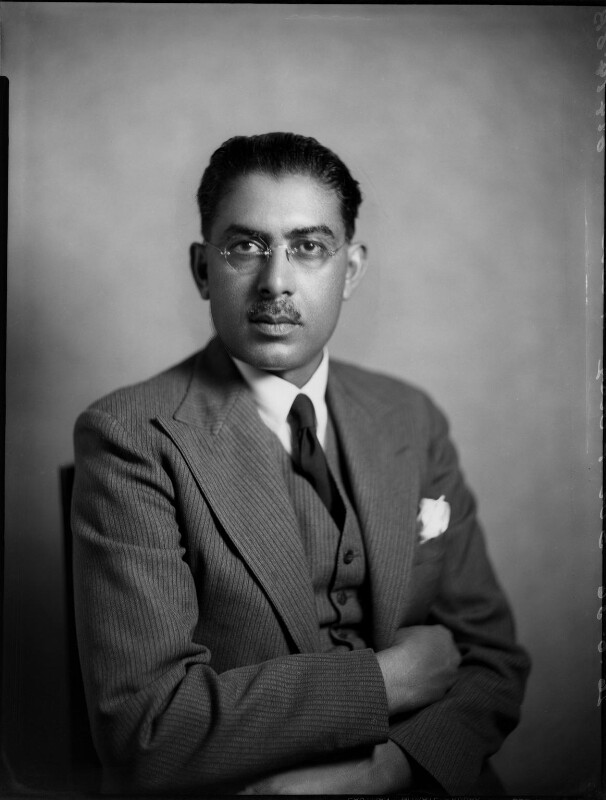

Hector Bolitho of New Zealand (1897-1974); author of 59 (!) books & biographer of George VI, Victoria & Albert and Edward VIII). Further Bio details.