My latest visit to Delhi luckily coincided with the World Book Fair, held from January 10-18 at the Bharat Mandapam Convention Centre (Pragati Maidan), which was unveiled in 2023 ahead of the G20 summit. The book fair has been held for over half a century, and I was looking forward to it, as it was going to be my first time. Once there, I felt a suitable sense of awe, amidst the sets of huge halls and the throbbing atmosphere around them.

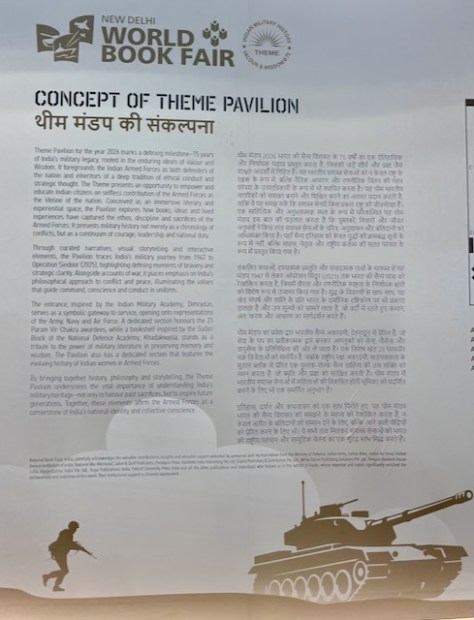

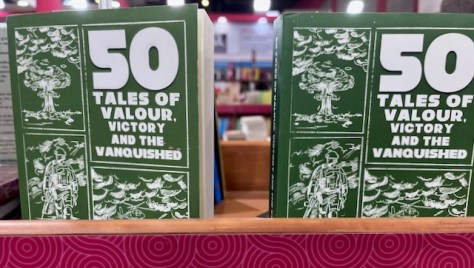

I was told this was the first time the fair had ‘free entry’, and the crowds were substantial, particularly around the stalls of major publishing houses. Secondly, this year’s theme was ‘Indian Military History: Valour and Wisdom@75.’ Book fairs are especially popular with schoolchildren and university students, and these young visitors were enthusiastically taking selfies with statues, exhibits and soldiers positioned there.

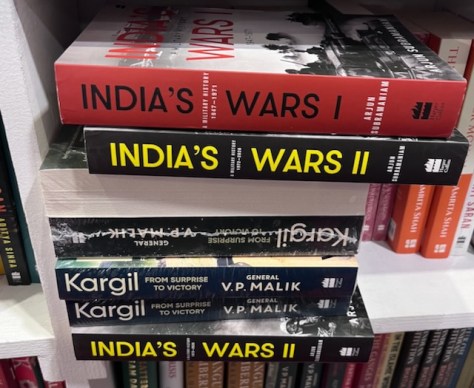

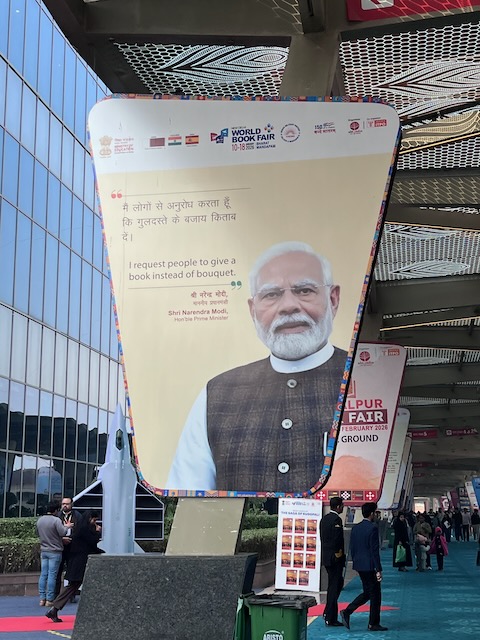

As I approached the entrance to the main hall, I was greeted by large posters encouraging young people to read and urging people to gift books, as the Fair is organised by the National Book Trust (Ministry of Education, Government of India) and the India Trade Promotion Organisation. Once inside, the presence of the military was immediately noticeable, as were the recent conflicts with neighbouring countries.

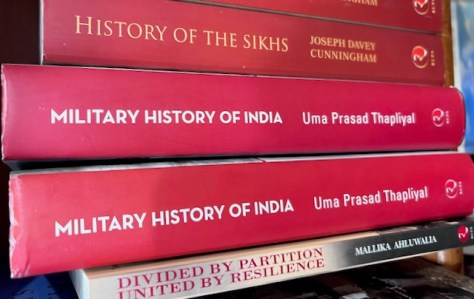

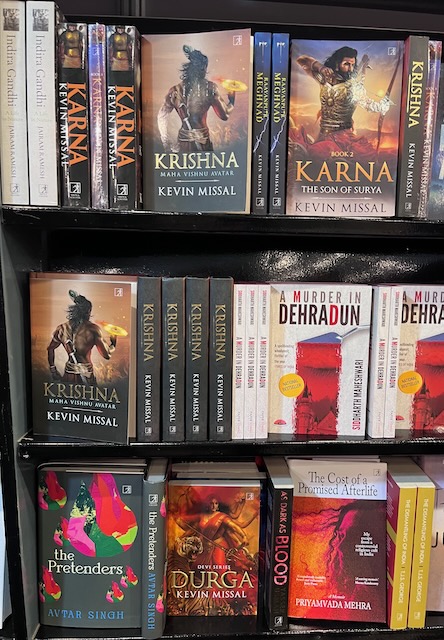

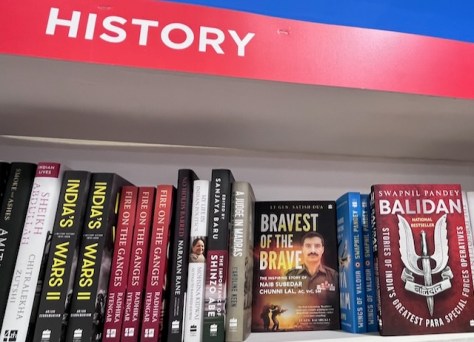

Having visited several bookshops in Delhi and Chandigarh on the trip, what had come into sharp focus was an abundance of material on military history and security studies by retired military personnel, commentators, and journalists. Popular history writing and their shelves in bookshops were never so narrowly dominated as they appeared to be now. Trends come and go, of course, and perhaps this is simply that, or perhaps something more.

The Machinery of Nationalist Discourse

In his seminal work, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983), Benedict Anderson argued that nations are socially constructed communities, imagined by people who perceive themselves as part of a group despite never meeting most of their fellow members. For our purpose here, Anderson also demonstrated how ‘print capitalism’ fuelled the rise of nationalism.

For instance, are publishers actively creating a market for narratives of conflict and war, or merely responding to demand for them? The reality is likely a mixture of both impulses. Print capitalism works by maximising circulation, leading publishers to print books designed to reach the broadest possible audience. The current surge in military history books and nationalist themes is neither coincidental nor has it emerged in a vacuum.

This trend is especially clear in India’s publishing scene. Since the 2010s, nationalist-revisionist history-writing, reshaping historical narratives, and revising textbooks have been major themes. The bookstores I visited showed this change: where history sections once had a variety of socio-cultural views on India’s multi-layered past, they are now filled with books highlighting post-1947 military bravery and intelligence activities.

Alongside my visit to the book fair, I attended a seminar at the PMML/NMML (Teen Murti), which also featured a spirited assertion of nationalism, while confining narratives of peace to nostalgic readings of the past. It was argued that these readings offer little evidence to support these sentiments, in this case regarding the Partition’s impact in Bengal. These discussions align with a global rise in populist nationalism, which privileges narratives of conflict.

Cinema as Nationalist Pedagogy

The Book Fair and the seminar are part of the same cultural milieu as the current hit film Dhurandhar. A review in The Caravan magazine has argued that the film exemplifies what happens when public discourse is consistently fed propagandist narratives. The review noted that if the goal is to serve nationalist propaganda to the masses, few mediums work better than a slickly produced, multi-starrer, action-packed spy thriller.

Conversely, an alternative to this swashbuckling sensationalism is the film Ikkis. Writing on the Scroll website, the reviewer noted that the film is based on Arun Khetarpal, who was posthumously awarded India’s highest gallantry award, the Param Vir Chakra, for his actions during the 1971 war. As Khetarpal’s deeds are well documented, Ikkis aims higher, seeking to understand what unites men sworn to kill each other.

The review added that the film eschews any vengeance-fuelled hyperbole, with scene after scene revealing the director’s efforts to resist jingoism. This sensitive reading of conflict and war has not resonated with audiences in the same way as Dhurandhar, which already has a sequel in the works. The Indian Express, describes Ikkis as a thoughtful exploration of masculinity and bravery that avoids Dhurandhar’s stylised machismo.

What do the divergent fortunes of these two films reveal, if anything important or long-term, about contemporary India’s cultural moment? Just as the book fair collection and the PMML/NMML discussion suggest a renewed contest over complex, layered narratives of identity, these two films capture two sides of the same coin. They represent the mixture of giving people what they want and offering them what their makers want them to want!

The Missing Voices

If Anderson’s ‘print capitalism’ helps us understand how mass media manufactures and disseminates narratives that shape national consciousness, it also reveals what is missing here: where are the voices of those who speak for peace and friendship? The current publishing industry, mirroring the broader political trend, seems to suggest that conflict is not only inevitable but desirable, a necessary component of national identity.

Yet surely, we do not all consider conflict the solution to our problems? When families feud, we try to keep talking and reach some form of amicable coexistence. Why should the same not apply to the family of nations? Instead, the religious-nationalist approach to history and politics, leisure and entertainment, which has gained prominence since the 1990s, aims to reduce content to a commodity and sentiment to profit.

The book fair’s public relations emphasis on military history and policy, then, reflects not only the sidelining or suppression of multiple voices but also an element of advertising to buyers and sellers of different kinds, enhancing familiarity and enabling involvement and investment. When every other book celebrates civilisational value and military valour against perennial ‘others’, alternative voices are drowned out not only by outrage and censorship but also by business.

A Reimagined Community

What I witnessed at the World Book Fair, across bookshops, at the Teen Murti seminar, and what I read about the contrasting fates of Dhurandhar and Ikkis show a nation-state actively reimagining itself. If nations are ‘imagined communities’, shaped by those who control the means of communication, then, as that act of imagining is never neutral, it can always be reimagined as well. They are shaped by choices, and those choices remain ours to make.

The question facing urban, middle India today is which version of itself it will choose to recall and reimagine: one defined primarily by categories, conflicts, and eternal revenge, or one that acknowledges complexities, accepts diversities, and accommodates differences. The contested marketplace of bookshops, cinemas, and talking shops (and their digital counterparts) will play a determining role in answering that question.

References:

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism, Verso Books, 1983.

Nandini Ramnath, ‘‘Ikkis’ review: In tribute to a war hero, a rare plea for peace and empathy’, Scroll, 1 January 2026

Surabhi Kanga, ‘The Mob Comes For Film Critics’, The Caravan, 1 January 2026

Marie Lall and Kusha Anand. Bridging Neoliberalism and Hindu Nationalism: the role of education in bringing about contemporary India. Policy Press, 2022.