I recently had the opportunity to revisit an old favourite place of mine, Purani Dilli, with a friend. Old Delhi, despite the wider socio-economic and political changes emanating from neighbouring New Delhi, retains much of its previous charm of being a vibrant and colourfully diverse locality. The constellations around Chandni Chowk and the labyrinth of narrow lanes overflowing with people, trade, and character, fill the hearts and bellies of locals and tourists alike. There are of course signs of change where the old meets the new, and reinvention is indeed necessary for survival. In this endeavour, the main thoroughfare has been pedestrianised, but cycle rickshaws and people continue to jostle for space. You can buy almost anything from here, it is a complete eco-system of co-existence.

History of the area

It was Shahjahan (r. 1628 –1658), the fifth great Mughal, who ordered his famous chief architect Ustad Ahmad Lahori (who also designed the Taj Mahal) to build this then-walled city between 1638 and 1649, which contained the imposing red sandstone fortress of Lal Qila and the Chandni Chowk, the main street. Shahjahanabad (abode of Shah Jahan), or as it is more popularly known as Purani Dilli/Old Delhi, refers to that walled city where the Mughal court, army, and household moved from Fatehpur Sikri in 1648, which then become the heartbeat and commercial centre of the empire.

Biswas (2018) notes that the city developed along an “organic street pattern…with signature characteristics such as different activities and trades, clusters of houses based on closeness and common interests and social ties, which it still depicts today. The lanes and the streets were designed for an easy movement of pedestrians and animal driven vehicles, which today have been taken over by two- wheelers, electronic and manual rickshaws…”

It remained the capital of the Mughals in India until the Revolt of 1857, by when the East India Company and afterwards the British Crown Rule had shifted the seat of power to Calcutta, only to return back to Delhi in 1911, where they too commenced with the construction of a new modern administrative headquarters designed by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, which was formally inaugurated in 1931. To distinguish between these two empires and spaces, the older city became Old Delhi and New Delhi become the new citadel with its palatial bungalows and manicured wide streets. Since 2019, the current BJP Government has commenced another phase of construction with the Central Vista Project led by a team under Bimal Patel. We can therefore see layer upon layer, phase after phase of architectural stamping, ushering in its own ideological imprint.

The Walled City

For nostalgia, a bygone era and character, especially for a historian, nothing matches Purani Dilli. The walled city brings with it rich heritage, historic buildings and the intimate liveliness of a small community.

Jain (2004) observes that “The Red Fort, Jama masjid and Chandni Chowk have been jewels in the crown of Shahjahanabad. Chandni Chowk is the centrepiece and dominant axis of the Walled City. The original Chandni Chowk had octagonal chowks with a water channel running through the centre. Its wide boulevard with prestigious buildings and bazar created a vista between the magnificent Red Fort and Fatehpuri Mosque. With the passage of time there has been an all-round degradation and deterioration of this glorious boulevard, which can be attributed to several reasons, like over-crowding, markets, wholesale trade, rickshaws and traffic, unauthorised constructions, conversion of heritage buildings, over-riding commercial interests and private motives, coupled with lack of controls.”

Composite culture

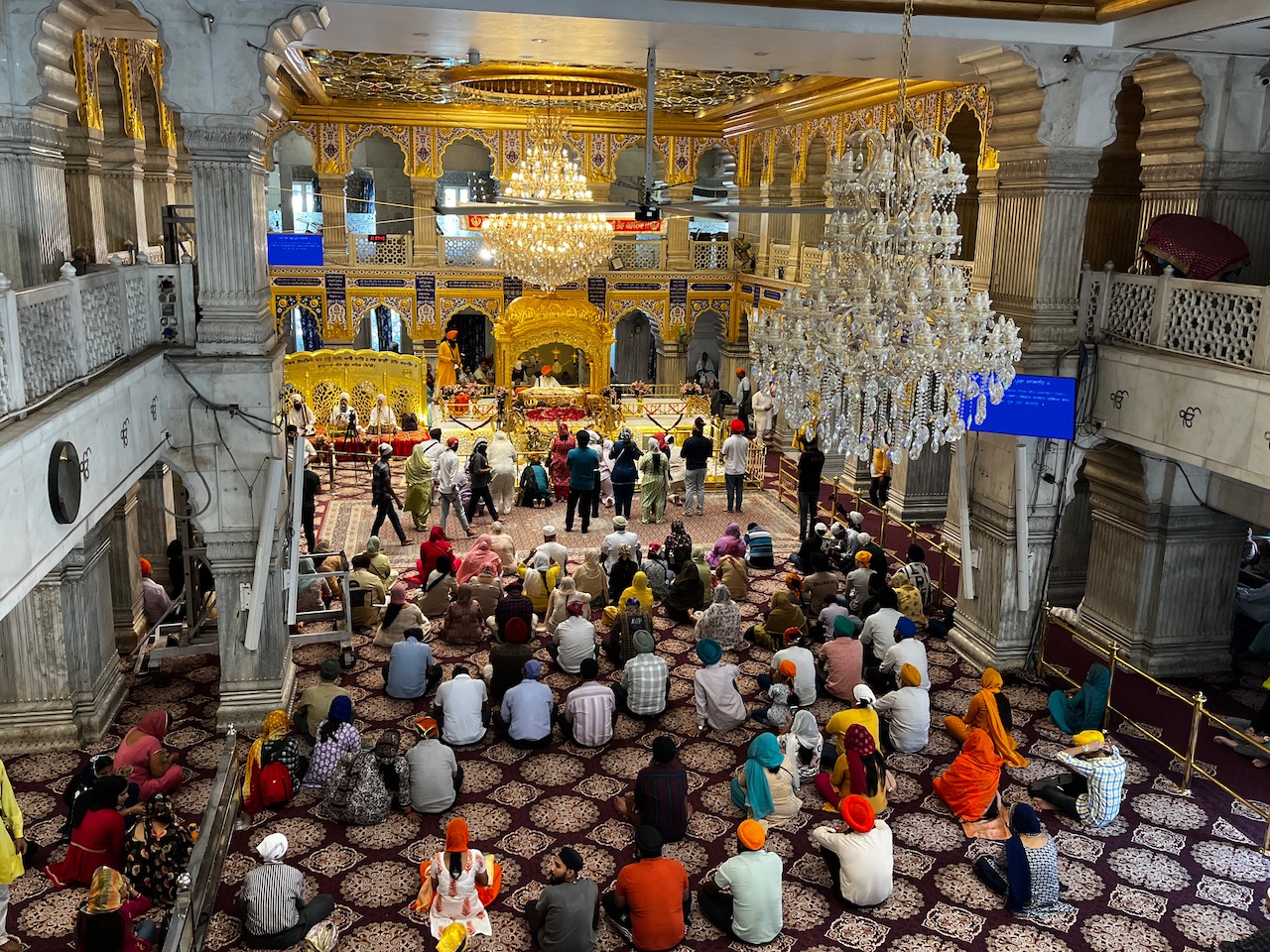

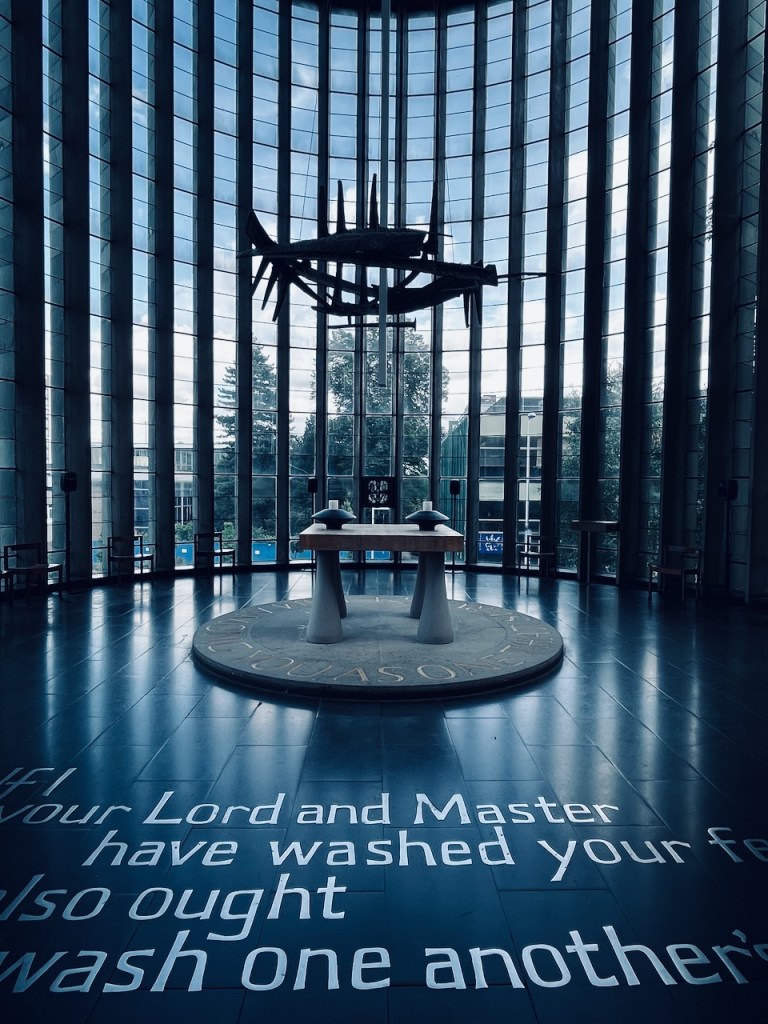

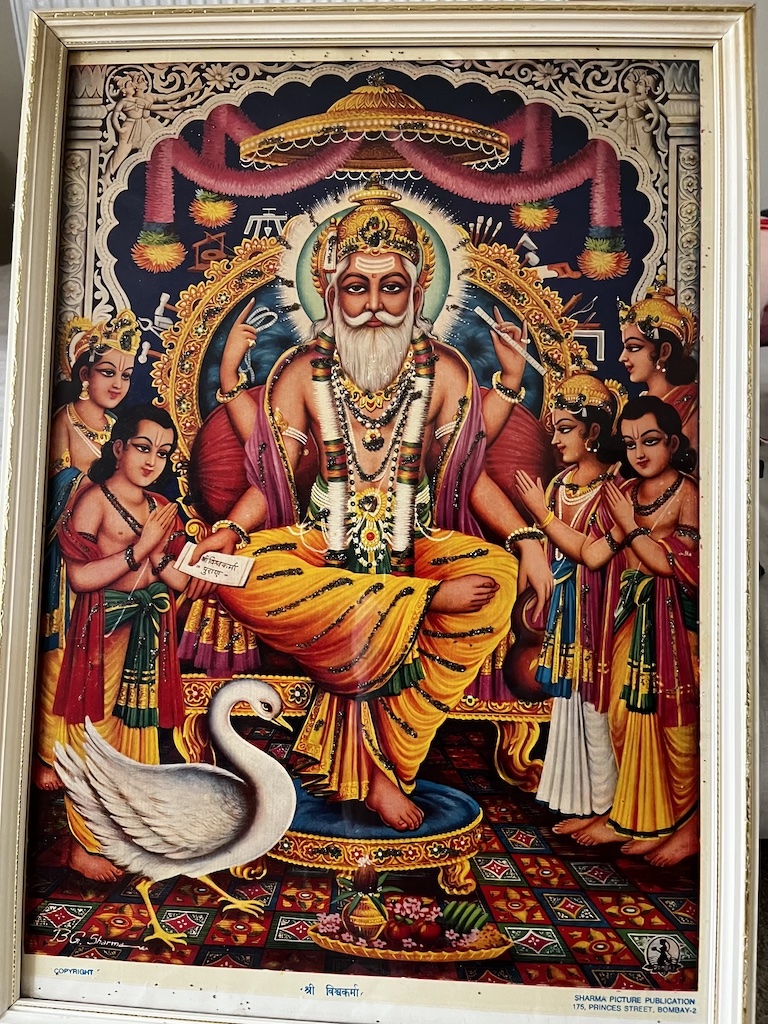

There are plenty of people who organise various walking tours of Old Delhi, as it attracts tourists from abroad and locals via the metro that has opened up the space that perhaps looked challenging before. My visit was an impromptu trip, I had some time and thought it would be nice to revisit this area after many years. I had planned to visit the Gurdwara, the Masjid and the Parathe wali gali! As I burnt off the parathas, the striking multi-faith milieu mingling into multi-cuisine eateries, left the heart warmed.

Biswas (2018) provides a detailed summary of the rich diversity present in Chandni Chowk. “In the northern sphere of the city, are the St. James’ Church (the oldest church in the city of Delhi), St. Mary’s Church, remains of Kashmiri Gate, Dara Shikoh’s library, the Lahori gate. In the southern part of the city, the key highlights are the Kalan Masjid, Ajmeri Gate, Holy Trinity Church, Razia Sultan’s grave, Turkman Gate, Havelis of Kucha Pati Ram, Anglo-Arabic School. With these divisions, the centre of the walled city is adorned with the harmonious street of Chandni Chowk, where the sacred spaces or the worship places of all major religions are located and co-exist amicably…The built heritage of the walled city comprises the grand Jama Masjid, the glorious Red Fort and many beautiful Jain temples of the two sects, numerous Hindu temples devoted to a multitude of gods, the Gurudwaras, the churches, the madrassas, the havelis of the Mughal and the post- Mughal era, still survive [ing] against their slaughter at the hands of the modernity.”

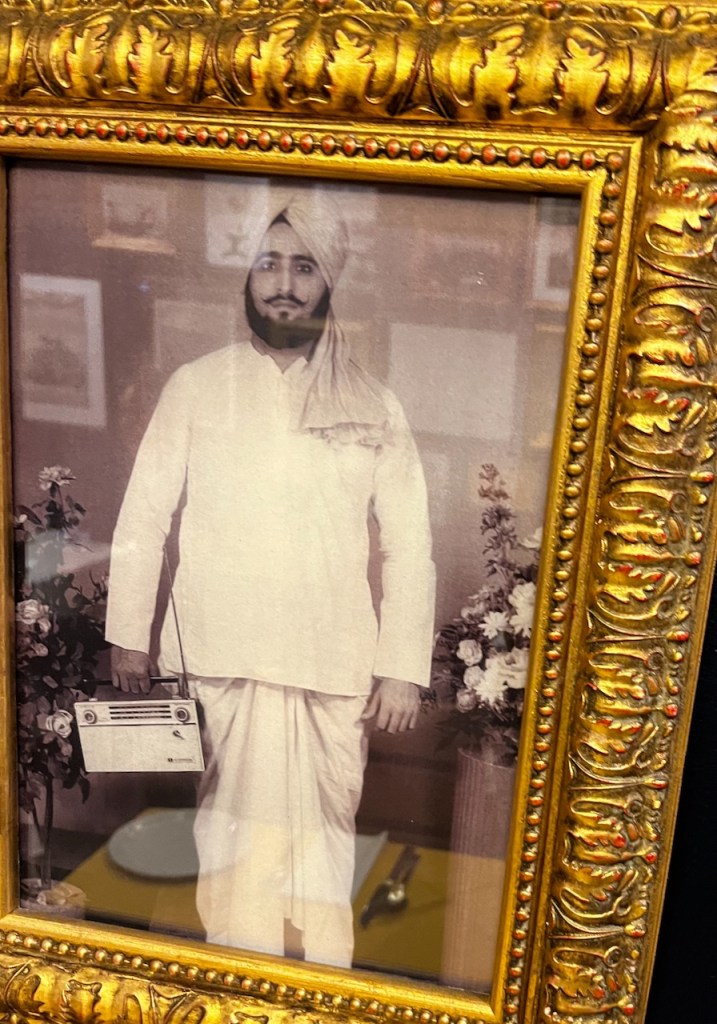

Undoubtedly the area has undergone change during the past 400 years, with each reign adding and leaving new layers. The walled city with the Qila and Masjid was the centre piece of the Mughal court, until the British transformed the former into military barracks. The British period marked by the revolt of 1857 saw vast areas being razed to the ground, some places only surviving due to the resultant outrage. With the birth of independent India in 1947, there was again vast destruction, loss of life and mass migration of people. The new contemporary socio-political anxieties mean we are perhaps less sure about the role of these places as they are confined to the past, while we celebrate and sell their associated heritage in the present. The Delhi Government is trying to beautify and make this a tourist hub, but that too must compete with conflicting agendas of the future. But for now, the spirit and roots of the Ganga-Jamuna Tehzeeb are quietly visible.

References and further reading:

Rana Safvi, Shahjahanabad: The Living City of Old Delhi, (HarperCollins India, 2020)

Swapna Liddle, Chandni Chowk: The Mughal City of Old Delhi, (Speaking Tiger, 2017)

Payushi Goel, Foram Bhavsar ‘Evaluating the Vitality of an Indian Market Street: The Case of Chandni Chowk, Delhi’ in Utpal Sharma, R. Parthasarathy, Dr Aparna (eds), Future is Urban: Liveability, Resilience & Resource Conservation (Routledge, 2023)

A.K. Jain, ‘Regeneration And Renewal Of Old Delhi (Shahjahanabad)’ ITPI Journal 1: 2 (2004) 29-38

Anukriti Gupta, ‘The Revolutionaries of Chandni Chowk’, 3 July 2021

Chitralekha, ‘In Paintings: Chandni Chowk of Delhi’, 21 January 2021

Jyoti Pandey Sharma, ‘Spatialising Leisure: Colonial Punjab’s Public Parks as a Paradigm of Modernity’, Tekton 1: 1 (2014) 14-30

Olivia Biswas ‘A Heart City: Celebrating The Pulsating Lifestyles Of The Walled City Of Delhi’ The 2018 WEI International Academic Conference Proceedings, Niagara Falls, Canada

Delhi Heritage Walks https://blog.delhiheritagewalks.com/category/heritage-walks/chandni-chowk-heritage-walks/

Leave a comment