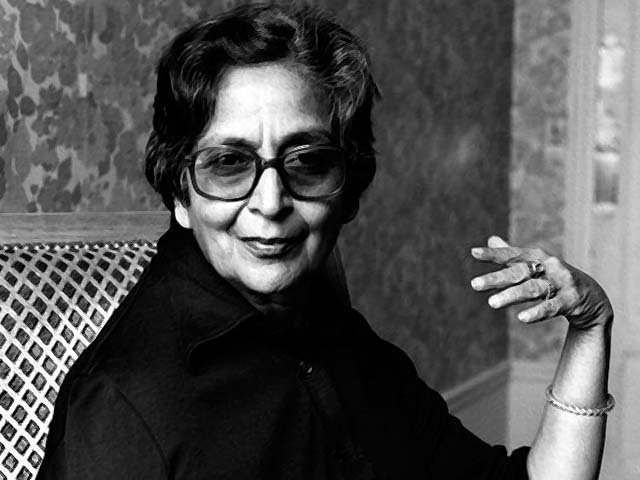

Amrita Pritam (1919-2005) was one the most distinguished Punjabi poets and fiction writers. She was born in Mandi Bahauddin, Punjab and was living in Lahore when in 1947 she, along with the millions others, was forced to migrate during the partition of the Punjab.

Her first collection of poems Amrit Lehrcm was published in 1936 when she was barely 17 years old. Starting as a romantic poet, she matured into a poetess of revolutionary ideas as a result of her involvement with the Progressive Movement in literature.

Ajj Aakhaan Waris Shah Nu (Today I Say unto Waris Shah) is a heartrending poem written during the riot-torn days that followed the partition of the country. (Apnaorg.com). The poem is addressed to Waris Shah, (1706 -1798), a Punjabi poet, best-known for his seminal work Heer Ranjha, based on the traditional folk tale of Heer and her lover Ranjha. Heer is considered one of the quintessential works of classical Punjabi literature.

Her body of work comprised over 100 books of poetry, fiction, biographies, essays, a collection of Punjabi folk songs and an autobiography that were all translated into several Indian and foreign languages

Ajj Aakhaan Waris Shah Nu (Today I Say unto Waris Shah – Ode to Waris Shah)

Translation from the original in Punjabi by Khushwant Singh. Amrita Pritam: Selected Poems. Ed Khushwant Singh. (Bharatiya Jnanpith Publication, 1992)

To Waris Shah I turn today!

Speak up from the graves midst which you lie!

In our book of love, turn the next leaf.

When one daughter of the Punjab did cry

You filled pages with songs of lamentation,

Today a hundred daughters cry

0 Waris to speak to you.

O friend of the sorrowing, rise and see your Punjab

Corpses are strewn on the pasture,

Blood runs in the Chenab.

Some hand hath mixed poison in our live rivers

The rivers in turn had irrigated the land.

From the rich land have sprouted venomous weeds

flow high the red has spread

How much the curse has bled!

The poisoned air blew into every wood

And turned the flute bamboo into snakes

They first stung the charmers who lost their antidotes

Then stung all that came their way

Their lips were bit, fangs everywhere.

The poison spread to all the lines

All of the Punjab turned blue.

Song was crushed in every throat;

Every spinning wheel’s thread was snapped;

Friends parted from one another;

The hum of spinning wheels fell silent.

All boats lost the moorings

And float rudderless on the stream

The swings on the peepuls’ branches

I lave crashed with the peepul tree.

Where the windpipe trilled songs of love

That flute has been lost

Ranjah and his brothers have lost their art.

Blood keeps falling upon the earth

Oozing out drop by drop from graves.

The queens of love

Weep in tombs.

It seems all people have become Qaidos,

Thieves of beauty and love

Where should I search out

Another Waris Shah.

Waris Shah

Open your grave;

Write a new page

In the book of love.

NOTES

Waris Shah (1706 -1798) was a Punjabi poet, best-known for his seminal work Heer Ranjha, based on the traditional folk tale of Heer and her lover Ranjha. Heer is considered one of the quintessential works of classical Punjabi literature.

Qaido – A maternal uncle of Heer in Heer Ranjha is the villain who betrays the lovers.

The Punjab – the region of the five rivers east of Indus: Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej.

I say unto Waris Shah by Amrita Pritam – Poem Analysis

Butalia, Urvashi. “Looking back on partition.” Contemporary South Asia 26, no. 3 (2018): 263-269.