It was Iqbal’s birth anniversary recently, and Purana Pakistan on Instagram had shared a poem he wrote in 1938; Shaam-o-Falasteen – Syria and Palestine. It prompted me to locate and share the political views of the political leadership at the time in British India. The views of both the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League were immensely sympathetic and supportive of the Palestinian people and their rights. It was framed in wider British imperialism, and for Nehru, “the Arab struggle against British imperialism in Palestine is as much part of the great world conflict as India’s struggle for freedom” (1936). Below I share a selection of views from Nehru, Jinnah, Gandhi and Iqbal.

NEHRU, 1936

Press statement issued by Jawaharlal Nehru, 13 June 13, 1936

Few people, I imagine, can withhold their deep sympathy from the Jews for the long centuries of the most terrible oppression to which they have been subjected all over Europe. Fewer still can repress their indignation at the barbarities and racial suppression of the Jews which the Nazis have indulged in during the last few years, and which continue today. Even outside Germany, Jew-baiting has become a favourite pastime of various fascist groups.

This revival in an intense form of racial intolerance and race war is utterly repugnant to me and I have been deeply distressed at the sufferings of vast numbers of people of the Jewish race. Many of these unfortunate exiles, with no country or home to call their own, are known to me, and some I consider it an honour to call my friends. I approach this question therefore with every sympathy for the Jews. So far as I am concerned, the racial or the religious issue does not affect my opinion.

But my reading of war-time and post-war history shows that there was a gross betrayal of the Arabs by British imperialism. The many promises that were made to them by Colonel Lawrence and others, on behalf of the British Government, and which resulted in the Arabs helping the British and Allied Powers during the war, were consistently ignored after the war was over. All the Arabs, in Syria, Iraq, Trans-Jordan and Palestine, smarted under this betrayal, but the position of the Arabs in Palestine was undoubtedly the worst of all.

Having been promised freedom and independence repeatedly from 1915 onwards, suddenly they found themselves converted into a mandatory territory with a new burden added on— the promise of the creation of a national home for the Jews — a burden which almost made it impossible for them to realise independence.

The Jews have a right to look to Jerusalem and their Holy Land and to have free access to them. But the position after the Balfour declaration was very different. A new state within a state was sought to be created in Palestine, an ever-growing state with the backing of British imperialism behind it, and the hope was held out that this new Jewish state would, in the near future, become so powerful in numbers and in economic position that it would dominate the whole of Palestine.

Zionist policy aimed at this domination and worked for it, though, I believe, some sections of Jewish opinion were opposed to this aggressive attitude. Inevitably, the Zionists opposed the Arabs and looked for protection and support to the British Government. Such case as the Zionists had might be called a moral one, their ancient associations with their Holy Land and their present reverence for it. One may sympathise with it. But what of the Arabs? For them also it was a holy land — both for the Muslim and the Christian Arabs.

For thirteen hundred years or more they had lived there and all their national and racial interests had taken strong roots there. Palestine was not an empty land fit for colonisation by outsiders. It was a well-populated and full land with little room for large numbers of colonists from abroad. Is it any wonder that the Arabs objected to this intrusion? And their objection grew as they realised that the aim of British imperialism was to make the Arab-Jew problem a permanent obstacle to their independence. We in India have sufficient experience of similar obstacles being placed in the way of our freedom by British imperialism.

It is quite possible that a number of Jews might have found a welcome in Palestine and settled down there. But when the Zionists came with the avowed object of pushing out the Arabs from all places of importance and of dominating the country, they could hardly be welcomed. And the fact that they have brought much money from outside and started industries and schools and universities cannot diminish the opposition of the Arabs, who see with dismay the prospect of their becoming permanently a subject race, dominated, politically and economically, by the Zionists and the British Government.

The problem of Palestine is thus essentially a nationalist one— a people struggling for independence against imperialist control and exploitation. It is not a racial or religious one. Perhaps some of our Muslim fellow countrymen extend their sympathy to the Arabs because of the religious bond.

But the Arabs are wiser and they lay stress only on nationalism and independence, and it is well to remember that all Arabs, Christian as well as Muslim, stand together in this struggle against British imperialism. Indeed, some of the most prominent leaders of the Arabs in this national struggle have been Christians.

If the Jews had been wise, they would have thrown in their lot with the Arab struggle for independence. Instead, they have chosen to side with British imperialism and to seek its protection against the people of the country….

The Arabs of Palestine will no doubt gain their independence, but this is likely to be a part of the larger unity of Arab peoples for which the countries of western Asia have so long hankered after, and this again will be part of the new order which will emerge out of present-day chaos. The Jews, if they are wise, will accept the teaching of history, and make friends with the Arabs and throw their weight on the side of the independence of Palestine, and not seek a position of advantage and dominance with the help of the imperialist power.

Selected and edited by Mridula Mukherjee, former Professor of History at JNU and former Director of Nehru Memorial Museum and Library.

IQBAL, 1937

Iqbal writing in response to the Peel Commission’s recommendations, July 1937

We must not forget that Palestine does not belong to England. She is holding it under a mandate from the League of Nations, which Muslim Asia is now learning to regard as an Anglo-French institution invented for the purpose of dividing the territories of weaker Muslim peoples. Nor does Palestine belong to the Jews who abandoned it of their own free will long before its possession by the Arabs.

Source: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2023/01/19/jinnah-iqbal-and-pakistans-historical-opposition-to-israel/

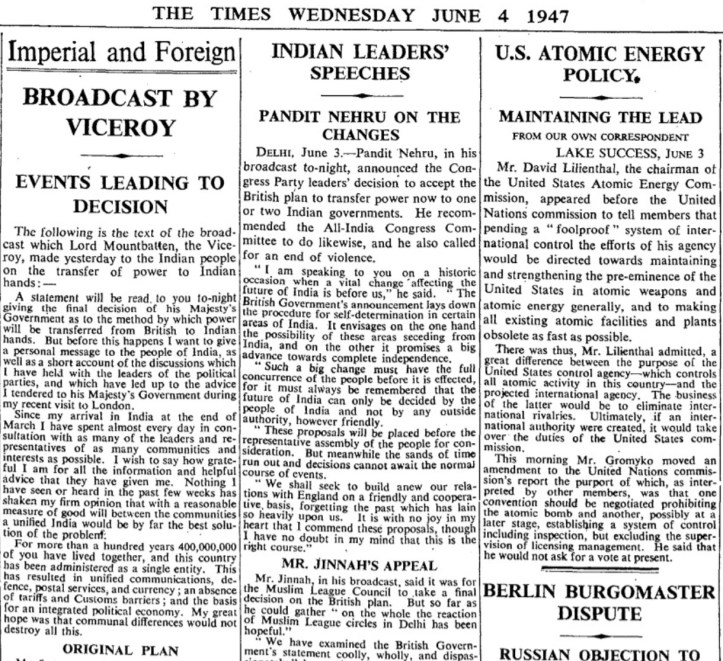

Jinnah, 1937

Mr. Jinnah in his presidential address to the AIML in 1937,

Great Britain has dishonored her proclamation to the Arabs – which had guaranteed to them complete independence of the Arab homelands…After having utilized them by giving them false promises, they installed themselves as the mandatory power with that infamous Balfour Declaration…fair-minded people will agree when I say that Great Britain will be digging its grave if she fails to honor her original proclamation…

You know the Arabs have been treated shamelessly—men who, fighting for the freedom of their country, have been described as gangsters, and subjected to all forms of repression. For defending their homelands, they are being put down at the point of the bayonet, and with the help of martial laws. But no nation, no people who are worth living as a nation, can achieve anything great without making great sacrifice such as the Arabs of Palestine are making.

Source: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2023/01/19/jinnah-iqbal-and-pakistans-historical-opposition-to-israel/

GANDHI, 1946

331. JEWS AND PALESTINE

Hitherto I have refrained practically from saying anything in public regarding the Jew-Arab controversy. I have done so for good reasons. That does not mean any want of interest in the question, but it does mean that I do not consider myself sufficiently equipped with knowledge for the purpose. For the same reason I have tried to evade many world events. Without airing my views on them, I have enough irons in the fire. But four lines of a newspaper column have done the trick and evoked a letter from a friend who has sent me a cutting which I would have missed but for the friend drawing my attention to it. It is true that I did say some such thing in the course of a long conversation with Mr. Louis Fischer on the subject. I do believe that the Jews have been cruelly wronged by the world. “Ghetto” is, so far as I am aware, the name given to Jewish locations in many parts of Europe. But for their heartless persecution, probably no question of return to Palestine would ever have arisen. The world should have been their home, if only for the sake of their distinguished contribution to it.

But, in my opinion, they have erred grievously in seeking to impose themselves on Palestine with the aid of America and Britain and now with the aid of naked terrorism. Their citizenship of the world should have and would have made them honoured guests of any country. Their thrift, their varied talent, their great industry should have made them welcome anywhere. It is a blot on the Christian world that they have been singled out, owing to a wrong reading of the New Testament, for prejudice against them. “If an individual Jew does a wrong, the whole Jewish world is to blame for it.” If an individual Jew like Einstein makes a great discovery or another composes unsurpassable music, the merit goes to the authors and not to the community to which they belong.

No wonder that my sympathy goes out to the Jews in their unenviably sad plight. But one would have thought adversity would teach them lessons of peace. Why should they depend upon American money or British arms for forcing themselves on an unwelcome land? Why should they resort to terrorism to make good their forcible landing in Palestine? If they were to adopt the matchless weapon of non-violence whose use their best Prophets have taught and which Jesus the Jew who gladly wore the crown of thorns bequeathed to a groaning world, their case would be the world’s and I have no doubt that among the many things that the Jews have given to the world, this would be the best and the brightest. It is twice blessed. It will make them happy and rich in the true sense of the word and it will be a soothing balm to the aching world.

PANCHGANI, July 14, 1946; Harijan, 21-7-1946

Source: https://www.gandhiashramsevagram.org/gandhi-literature/mahatma-gandhi-collected-works-volume-91.pdf

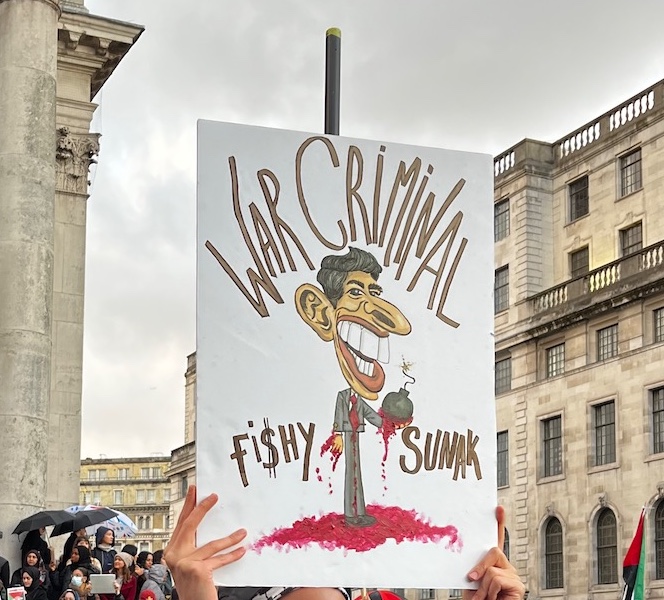

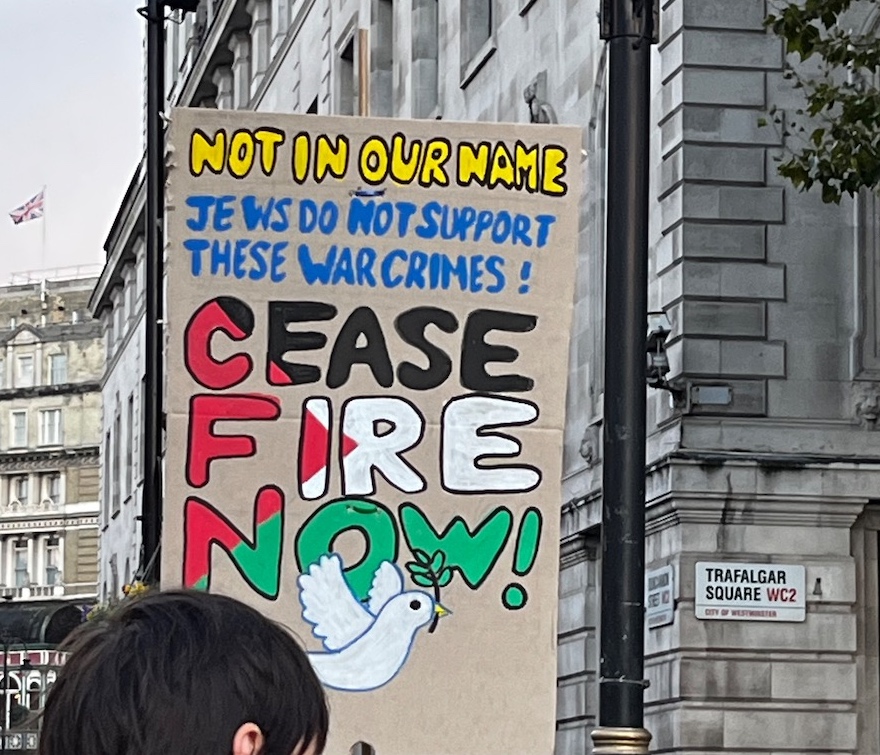

Below are a selection of photos from a recent protest in London.