In January 1972, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman — released from prison in Pakistan — flew to independent Bangladesh from Rawalpindi (Pakistan) via London and …

Mujibur Rahman’s First Secret Meeting with an Indian Officer — Me

In January 1972, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman — released from prison in Pakistan — flew to independent Bangladesh from Rawalpindi (Pakistan) via London and …

Mujibur Rahman’s First Secret Meeting with an Indian Officer — Me

In this year of 2020, as debates are generated around Government of Pakistan’s new single national curriculum and its comparison with Government of India’s new national education policy, mind goes back to the first attempts made by a different Government of Pakistan, ‘to evolve a comprehensive national plan in accord with the Objectives Resolution’ of March 1949 (File No. 3 (4)-PMS/50, GoP, PMS).

Fazlur Rahman, then-Minister for Commerce & Education, was born in then-Dacca and was a lawyer-politician of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League, who had served as Revenue Minister of the pre-partitioned province. On 14 September 1949, he sent a 14-page letter (F. No. 14-313/49-Est) to Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, in which he set out his trenchant comments and an accompanying template for the ‘two-fold task’ confronting them namely (1) ‘to lay the foundations of an educational system based on “Islam”’ and (2) to imbue children ‘with an international outlook’.

Recalling the first Pakistan Educational Conference of November 1947 and its resultant educational ideology and institutions – ‘the Advisory Board of Education, the Council of Technical Education and the Inter-University Board’ – he felt that the time had come to overcome ‘the existing system of education, with its alien background, Hindu and Christian ideas, foreign to our ideology’, for as long as it continued, it could not be expected ‘to produce men and women who would realise the value of the Islamic way of life and would make loyal and zealous citizens of Pakistan’.

For the successful achievement of this task, two things were essential: (i) text-books and (ii) teachers. As far as text-books were concerned, the need for Rahman was ‘to draw up the syllabus for every subject on the basis of Islamic ideology (as distinct from instruction in Islamic theology) and get text-books written by competent authors’. He wanted ‘Urdu readers – fundamentally the same all over Pakistan’, necessitating ‘a change in the existing system of publication – whose sole motive is profit-making’. Thus, ‘the Central Government should have them written under supervision’.

There was also the matter of ‘compiling a national history as a kind of reference book’ comprising researched topics like (a) ‘Islamic history and civilisation, (b) the rise and fall of Muslim states all over the world and (c) the contribution made by Muslims to the Indo-Pakistan sub-continent’. For the adoption of Islamic ideology, it was ‘essential to establish a Research Institute in Islamiyat’. As regards teachers and their training, ‘a number of Central Training Institutions’ were needed. These two were ‘fundamental problems which exclusively concerned the Central Government’.

While education was constitutionally the responsibility of the provinces – like in India – their ‘limited resources’ and its ‘all-Pakistan character’ made it ‘incumbent on the Central Government’ to take the lead – ‘from adult to university education’. For ‘democracy and illiteracy go ill together. The illiteracy percentage for India [before 1947] was nearly 90, but with the establishment of Pakistan and the exodus of non-Muslims (educationally more advanced) and the influx of Muslim refugees (to a large extent illiterate)’, there was an increased mass illiteracy in Pakistan.

Adult education, however, was not ‘mere imparting of literacy’ but included ‘spiritual, civic and vocational motives’ for the creation of a patriotic and productive citizenry. This involved infrastructure, implements, literature, teachers and audio-visual aids, for the provision of which, ‘the Central Government must assume certain powers’. Equally important was ‘the provision of free, universal, compulsory primary education’, involving a vast expenditure. ‘Free, compulsory secondary education’ was ‘unfeasible and must be left to future’.

Anyhow, the Central Government had the ‘clear responsibility’ to produce ‘patriotic citizens not warped by narrow provincialism or alien cultural elements as the Hindu influence in East Bengal’. National solidarity therefore required ‘the speedy revision of curricula and syllabi and re-writing of textbooks’. Another problem was the ‘place of Urdu in national life’. As Jinnah had made it ‘abundantly clear’ that Urdu was to be ‘the national language’ and as, by adopting Hindi in Devanagari script, India had ‘dealt a blow’ to Urdu – ‘the cultural heritage of Indian Muslims’.

For Rahman, language was a ‘potent means’ to maintain ‘cultural ascendancy and a separate political consciousness’. Urdu with its Persian and Arabic words was ‘alien in spirit to Hindu culture’, essentialising its ‘elimination from Indian national life’. Conversely, in Pakistan it was ‘a matter of vital necessity to have Urdu in Arabic declared forthwith as state language, a compulsory subject in schools’ overcoming the ‘narrow provincialism’ and ‘parochial mentality’ of East Bengal and Sind and resistance of West Punjab and NWFP ‘to assimilate the vocabulary and culture of these two’.

It was a no-brainer for ‘all employees of the Central Government be required to know Urdu’ and a Bureau of Translation be set up for all technical-scientific terms. In this connection, it is important to remember that in 1949, the Hindu community in East Bengal constituted one third of its population, among whom were ‘the caste Hindus – wedded to the Bengali language – the hard-core of resistance’. Rahman was concerned about their potential for ‘an anti-national mentality’ without ‘a pro-Islamic outlook’; ‘dependable citizens of Pakistan with due regard to their religious rights’.

His suggestion was to ‘reconstruct the Bengali language’ with ‘the Arabic script’ thereby ‘putting an end to the disruptive activity being carried in the name of the common culture of the two Bengals’. Moreover, the ‘present Bengali language with its Sanskrit script’ was ‘steeped in Hindu influence, full of Sanskrit words, Hindu mythology and [thus] anti-Islamic’. The Arabic script would ‘eliminate Hindu influence, facilitate adult education, link up East and West Pakistan [and] ensure East Bengal’s willing acceptance of Urdu as a national language’.

In technical education, Pakistan then had only 3 ‘engineering colleges’, like its 3 universities, for a population of 80 million, ‘impaired by the exodus of non-Muslim teachers’. A ‘Grants Committee’ for both was needed. Here, the ‘main obstacle’ was ‘the attitude of the Ministry of Finance’, to which education was a ‘provincial responsibility’. Rahman had forged the establishment of a History Board, Adult Education Centres in East Bengal, a Central Syllabus Committee with its Bengali sub-committee, a Committee of adopting Arabic script and a Committee on Technical Education.

His future proposals were less piece-meal and included the Central Government assuming ‘direct responsibility for the general planning and coordination of education’, a central-provincial sharing of adult education expenditure, central financial assistance for free, compulsory primary education in provinces, Urdu as state language, Arabic script for regional languages and centres for translation, Islamiyat, teachers’ training and a University Grants Committee.

Special report: The founding fathers 1947-1951. The season of light… By Dr Syed Jaffar Ahmed, Dawn.

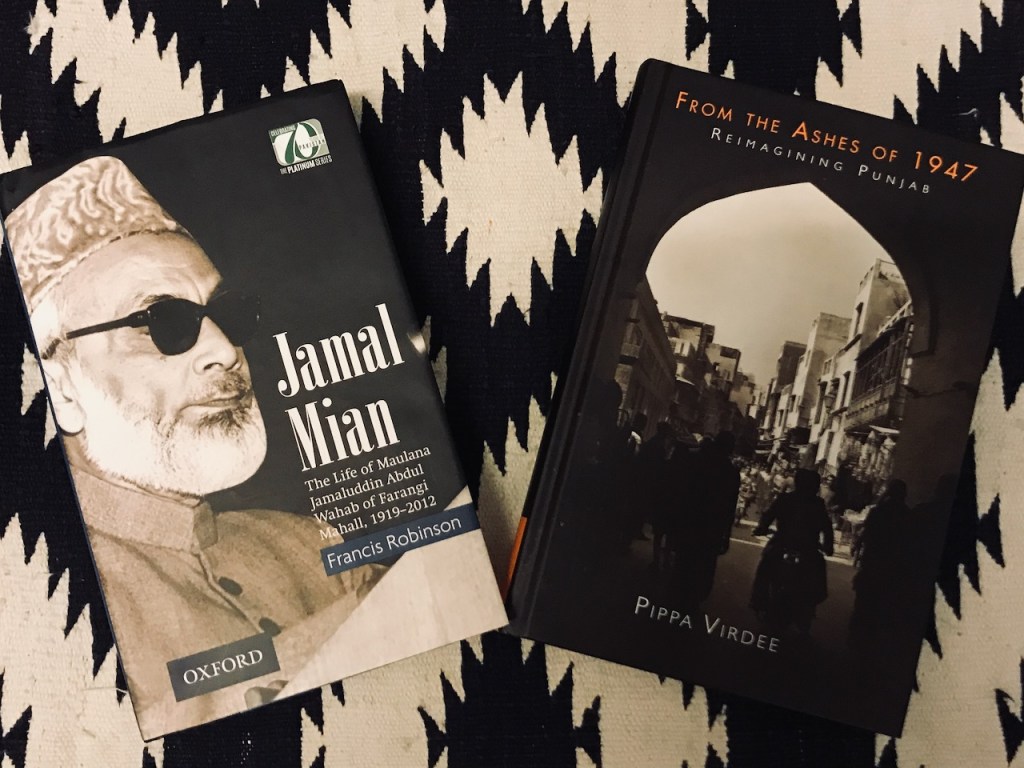

TWO books reviewed of A time BYGONE

ONE is the biography of Jamal Mian (1919-2012), a life across British India, independent India, East Pakistan and Pakistan. The kind of life, which would be unimaginable to most people of the subcontinent today. At the core, this is a detailed history of the changing political landscape of North India told through the life and times of an extraordinary life. The story unfolds with authority and simplicity, the kind of old-fashioned narrative history writing that barely exists. Stories and history writing are barely written like like because they do not command the short-term impact and they take years, generations to unfold through the relationship of the historian and his subject. But importantly it brings together the life and times of an individual and his milieu – showcasing the kind of “Hindustan” that no longer exists, other than in history books.

Pippa Virdee, FRANCIS ROBINSON. Jamal Mian: The Life of Maulana Jamaluddin Abdul Wahab of Farangi Mahall, 1919–2012, The English Historical Review, ceaa186, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ceaa186

TWO is an account of the province(s) of Punjab; rising From the Ashes of 1947 but simultaneously being reimagined. This too is about a political landscape that has been transformed and only exists in the history books, kinder memories and sepia imaginations of some of its people. It is about the shorter, shocking and longer, hardening consequences of dividing the land of five rivers. It too has been written over a long period and reveals the changing nature of my understanding of Partition, from the beginning of my doctoral work in 2000, to the point of this publication in 2017. It has changed further still because history is about engaging with the past through the unfolding present and “reveals how far nostalgia combined with the lingering aftershocks of trauma and displacement have shaped memories and identities in the decades since 1947.”

Sarah Ansari, PIPPA VIRDEE. From the Ashes of 1947: Reimagining Punjab, The American Historical Review, Volume 125, Issue 2, April 2020, Pages 635–636, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhz695

When Pakistan was created in August 1947, it was made up of two wings, East and West. In 1951, when its first census took place, the combined population of both wings was 76 million; 34 million in West and 42 million in East. The Bengalis made up the majority of the population of East and this made Bengali/Bangla the language spoken by the numerical majority of Pakistan. But Urdu was seen as the national language, while being the mother tongue of barely 5 per cent of the population then. However, it was more than a language; it was attached to the very core of the Pakistan Movement as the Quaid-i-Azam Mohd. Ali Jinnah declared in Dacca (Dhaka) in 1948. Yet, soon thereafter, the fractures and fissures between the two wings began to open up, due to the discriminatory and step-brotherly treatment of the East Pakistanis; not just in the language sphere.

By 1952, there were large-scale demonstrations and unrest centred around the University of Dhaka and on 21 February 1952, these ended in violence, in which the police clamped down on the protestors resulting in numerous casualties. Since 2000, the United Nations has observed 21 February as the International Mother Language Day. Bengali/Bangla was eventually recognised as an official language of Pakistan (alongside Urdu) in article 214(1), when the first constitution of Pakistan was enacted on 29 February 1956. Longer term though, this parity in the Constitution failed to address the underpinning problems and East Pakistan eventually became Bangladesh following the civil war of 1971.

The letter below, sent a week after these protests, from Malik Firoz Khan Noon, a prominent landowning Punjabi and future PM (1957-58) of Pakistan, then-Governor, East Bengal Governor to Sir Khwaja Nazimuddin, an aristocrat Bengali and Jinnah’s successor as Governor-General (1948-51) of Pakistan, then-PM (1951-53), shows the failure to recognise the legitimate grievances of the language movement.

Noon to Nazimuddin, 28 February 1952

The Vice-Chancellor and other members of the Executive Committee have closed the University. Some students are leaving: others will try to hang on in Dacca. Out in the districts no untoward incidents have taken place except this that students have been trying to make themselves a nuisance at railway stations and in the cities, and the papers who write explaining true facts are not allowed by the students to be distributed by the hawkers in the district headquarter towns. The Government are now planning to drop pamphlets from the air throughout the province. I do not think that the Muslim League Ministers or other leaders can go out into the province as yet for three or four weeks to explain their point of view, but our propaganda has been very weak: almost non-existent. The Government point of view has not had the chance to go before the public yet.

I feel that both in Western Pakistan and in East Pakistan our propaganda machine should be put into full force and the true situation exposed to the public, viz. that this was a conspiracy between the communists and some of the caste Hindus of Calcutta, and certain political elements in East Pakistan who wanted to replace the Ministry: the students were made the cat’s paw. Their idea was to set up a puppet Ministry here, with Fazlul Huq as the Chief Minister, and then negotiations were to start for the unification of the two Bengals. I feel that it is most important that this true position must be exposed to the public who should realise the danger that we still continue to face in this province. The language question was only a subterfuge very cleverly exploited. In this province we are doing what we can to put forth our point of view, and Mr Fazl-i-Karim – Education Secretary – who has just returned from abroad has been asked to take charge of this work.

The second point to which I should like to draw your attention is that during the coming session of the Central Legislature, this Bengali language question must be settled once for all, and I do not think that you can get out of it without accepting Bengali as one of the state languages, but it must be Bengali written in the Arabic script. The sooner this resolution is passed the sooner will this controversy be settled. I have no doubt that the Hindus will create trouble about the script, but no Muslim will be able to raise his voice against the Arabic script, because in this way we shall have all the Provincial languages written in the same Arabic script, and this is most essential from the national point of view. I am told that during the time of Shaista Khan, Bengali was written in the Arabic script: there are some books in the museum here written in that script. If Bengali were written in the Arabic script – 85 % of the words being common between Urdu and Arabic if properly pronounced soon a new and richer language will emerge which may be called ‘Pakistani’. But something has to be done in this matter. We cannot let matters adrift.

The Arabic script will be the biggest disappointment to the Hindus who have been at the bottom of it, and that is the real crux of the whole question. The Jamiat ul Ulama-i-Islam in this province under the presidency of Pir Sahib of Sarsina and Secretary-ship of Maulana Raghib Asan have already passed a resolution demanding the writing of Bengali in the Arabic script, and no Muslim M.L.A. – either in Karachi or here – will be able to oppose the Arabic script. As a matter of fact, the Muslim League Party here last year went to the extent of passing a resolution saying that Arabic should be the national language of Pakistan. The object really was to do away with Urdu, but it is certainly a point which may be used by you in your speech, if necessary. The Aga Khan has written a very good pamphlet on this subject. It was going to be published but unfortunately it has been burnt with the Jubilee Press. The Aga Khan has promised his followers to be provided with a revised copy and I will try and let you have one as soon as it becomes available.

One of the main points the Aga Khan brought out was this that Persia changed their script from the old Pehlvi script into the Arabic script and in that way their literature became richer than ever, and by changing the script the Persian language did not lose anything nor would the Bengali language. He also tried and impressed that by enforcing the Arabic script the Bengali literature will be available to all other Muslim countries who will be able to appreciate the work of the Bengali authors. Similarly, the literature of all other Muslim countries will be open to Bengali Musalmans who know the Arabic script. He also pointed out in his pamphlet that every Musalman has to learn Arabic in any case because the boys and girls must read the holy Quran, and if they are conversant with the Arabic script why should this Dev Nagri script be thrust on them unnecessarily. It will be conceded on all hands that if in the schools in East Bengal boys and parents were given the option for children to learn Bengali either in the Arabic script or in the Dev Nagri script, they would all choose the Arabic script.

Quite a large amount of money is being earned by Calcutta Hindu authors who have the monopoly of all our school text books and it is they who are spending money in support of the Bengali language and would even spend money in support of the Dev Nagri Script. It should not be forgotten that people in West Bengal themselves have not asked for Bengali language to be accepted as a State language in Bharat: they have accepted Hindi as their national language.

Further Reading:

Rahman, Tariq. ‘Language and ethnicity in Pakistan‘ Asian Survey 37, no. 9 (1997): 833-839.

S.M. Shamsul Alam (1991) ‘Language as political articulation: East Bengal in 1952’, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 21:4, 469-487, DOI: 10.1080/00472339180000311

Tarun Rahman, ‘The Bengali Story Behind International Mother Language Day‘, Medium, 11 February 2016

Salman Al-Azami, ‘The Bangla Language Movement and Ghulam Azam‘, Open Democracy, 21 February 2013

To commemorate the first session at Dacca, East Pakistan, of the National Assembly of Pakistan, three postage stamps were issued on and from the 15th October 1956:—

The picture above is the first day cover with a 1 ½ anna stamp. I just came across it during a stroll at the book fair on The Mall, Lahore which is held on Sundays. The commemorative stamp was issued on the eve of Pakistan becoming the first Islamic Republic in the world. At the time Pakistan was made up of two wings, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and West Pakistan. The National Assembly of Pakistan is the lower house of parliament and initially met in the capital Karachi. However, this was the first session of the National Assembly in Dacca and in fact the last time as well because two years later Ayub Khan became the first military dictator in Pakistan and eventually by the 1971, the country was on the brink of splitting up.

The stamp encapsulates the period when Pakistan ended its status as a dominion and was declared an Islamic Republic of Pakistan on 23 March. Hence this is day is celebrated as Republic Day in Pakistan. This of course is also the same day that Mohammad Ali Jinnah adopted the Pakistan Resolution (Lahore Resolution) outlining the two-nation theory. The full text of the 1940 Resolution is available via: http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00islamlinks/txt_jinnah_lahore_1940.html.

The Constituent Assembly became the interim National Assembly with Governor General Iskander Mirza as the first President of Pakistan. The Assembly had 80 members, half each from East Pakistan and West Pakistan. A turning point in Pakistan’s history, the Constitution required the president to be a Muslim and he (typically it was a he), had the power appoint the Prime Minister and he was also empowered with the ability to remove the Prime Minister, if there was a lack of confidence in his abilities. The Constitution of 1956 was written almost ten years after Pakistan was created, but crucially it set in motion a dangerous precedent; the President had the power to suspend fundamental rights in case of an emergency. Crucially though the Constitution of 1956 was short-lived because by 7 October, 1958, General Mirza dissolved the constitution and declared Martial law in Pakistan.