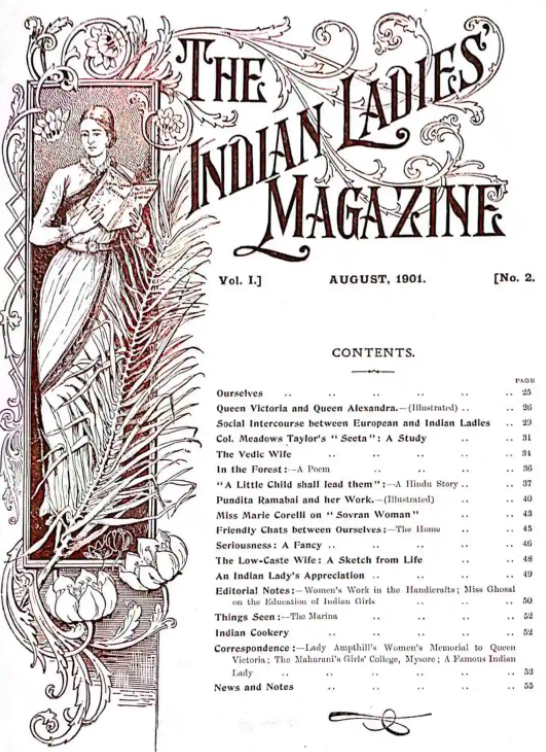

Recently I noticed in several social media forums that people have been sharing details of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain and her short story, Sultana’s Dream (1905). This story was originally published in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine, Madras, 1905, in English and translated by the author into Bengali. The story takes the form of a dream, set in a futuristic feministic world, in which women through education, opportunity and their innovative ability to use technology have been able to flourish. The science and technology featured in the story is not far off the realities of today and shows immense foresight by the imagination of the author.

The story also highlights how unjust it was, and still is, to deny women education and freedoms, which men have. The imagined place is a generous, green, and friendly environment, in which feminist science has created a space for everyone to thrive and reap the benefits. Although the story was published over a hundred years ago, we are still far from this utopian land.

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain was born circ. 1880 to an orthodox Bengali Muslim upper-class family in the small village of Pairaband (district Rangpur in Bengal Presidency and present-day Bangladesh). Her father insisted that she learn only Arabic and remain in strict purdah. But with the assistance of her siblings, she learned to read and write Bangla and English. In 1896 her older brother Ibrahim Saber sought to arrange her marriage to a widower in his late 30s. Syed Sakhawat Hossain was the district magistrate in the Bihar region of Bengal Presidency and Ibrahim thought Rokeya would do well under Syed’s open-minded attitude, who had received education in both Bengal and London.

“Rokeya and her husband settled in Bhagalpur, Bihar. None of her children lived. Syed, who was convinced that the education of women was the best way to cure the ills of his society, encouraged his willing wife to write, and set aside 10,000 rupees to start a school for Muslim women.”

After 11 years of marriage, Syed passed away in 1909, leaving Rokeya alone. Soon thereafter she opened a school in Bhagalpur. Later, she moved to Calcutta where she re-opened the Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ School on March 16, 1911. The number of students went from 8 in 1911 to 84 in 1915.

[Source: Hossain, Rokeya Sakhawat – Postcolonial Studies (emory.edu)]

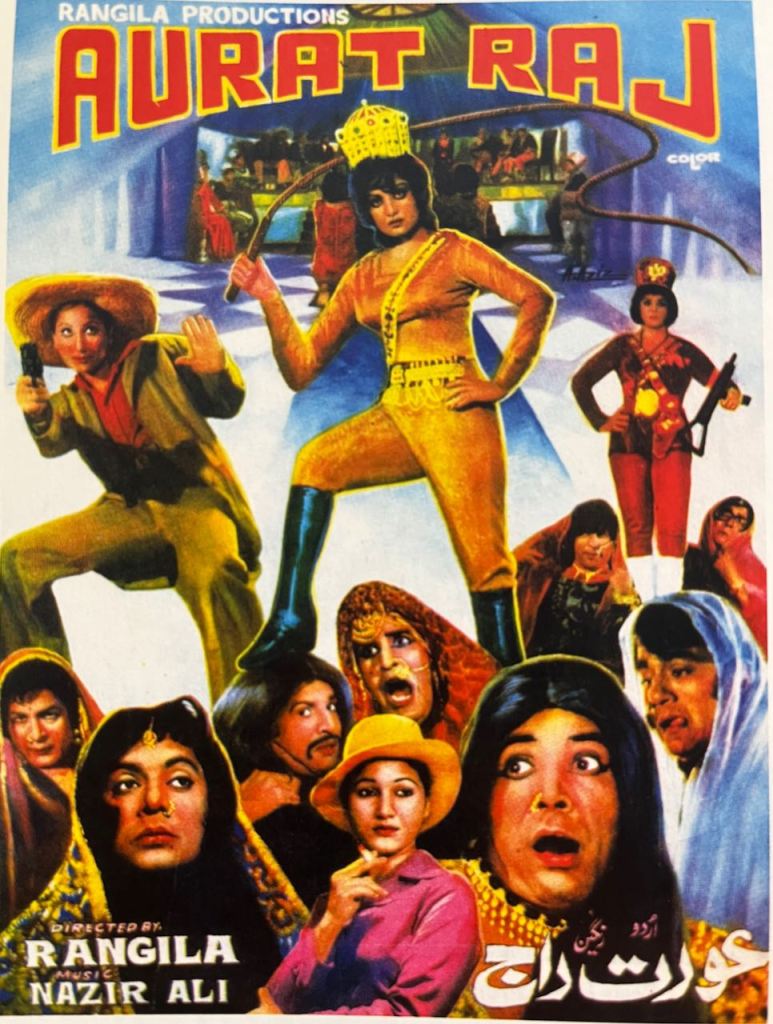

The pioneering concept behind Sultana’s Dream has inevitably inspired other writers and artists to take their cue from a world in which women have the power and men are the submissive other. Aurat Raj, a 1979 Pakistani film, which on the surface appears to be inspired by Rokeya’s work, is also a commentary on the military (and masculine) regime that had come into power, under General Zia. Aurat Raj, is a strange and kitsch interpretation, at whose heart is a social message, centred on exposing the oppression of women. But when the roles are reversed, the women behave in a similar fashion too, unlike Hossain’s short story.

The poster for the film Aurat Raj is equally intriguing as the film itself. It “depicts a woman dressed in a tight-fitting suit and long boots with a crown on her head and a whip in hand, all the more intriguing. She has a commanding, imperious expression on her face. To her right another woman in men’s clothes brandishes a gun. A third woman confidently smokes a cigarette. At the feet of the ‘Empress’ a series of men, including Sultan Rahi, are dressed in women’s clothes. Rahi demurely wears a dupatta on his head, his expression one of effeminate alarm. A subversive and experimental drag movie directed by Rangeela, who had appeared in scores of films in side-comic roles usually playing to the front benchers, Aurat Raj is perhaps Pakistan’s only satire to date and it lampoons not only the naked chauvinism that prevails in Pakistani society but also pokes fun at the way that this attitude pervades the industry. The film targets the machismo of Pakistani men and revels in inverting the gender and power roles, making the women literally wear the pants and leaving the men, including Sultan Rahi and Waheed Murad, wearing frilly frocks and helpless expressions.” Ali Khan, “Film Poster: Reflections of Change in the Pakistani Film Industry” in Cinema and Society: Film and Social Change in Pakistan, edited by Ali Khan & Ali Nobil Ahmad (OUP, 2016), P251.

Despite its well-known star cast of Waheed Murad, Rani, Rangeela and Sultan Rahi, the film was a commercial flop. However, it is certainly worth revisiting, if only as a reminder of the subversive message of the film, which dreams of a more equal society.

Read further:

Sound of Lollywood: When men turned into dupatta-covered minions in ‘Aurat Rar’ by Nate Rabe, 15 April 2017.

Online edition available to read: Sultana’s Dream. (upenn.edu)

The manless world of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain – DAWN.COM by Rafia Zakaria, 13 December 2013.

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain — a pioneer of women’s education who strove for a feminist utopia (theprint.in) by Taran Deol, 9 December 2020.

Watch the animation of Sultana’s Dream by WOW Festival Pakistan: