This slideshow requires JavaScript.

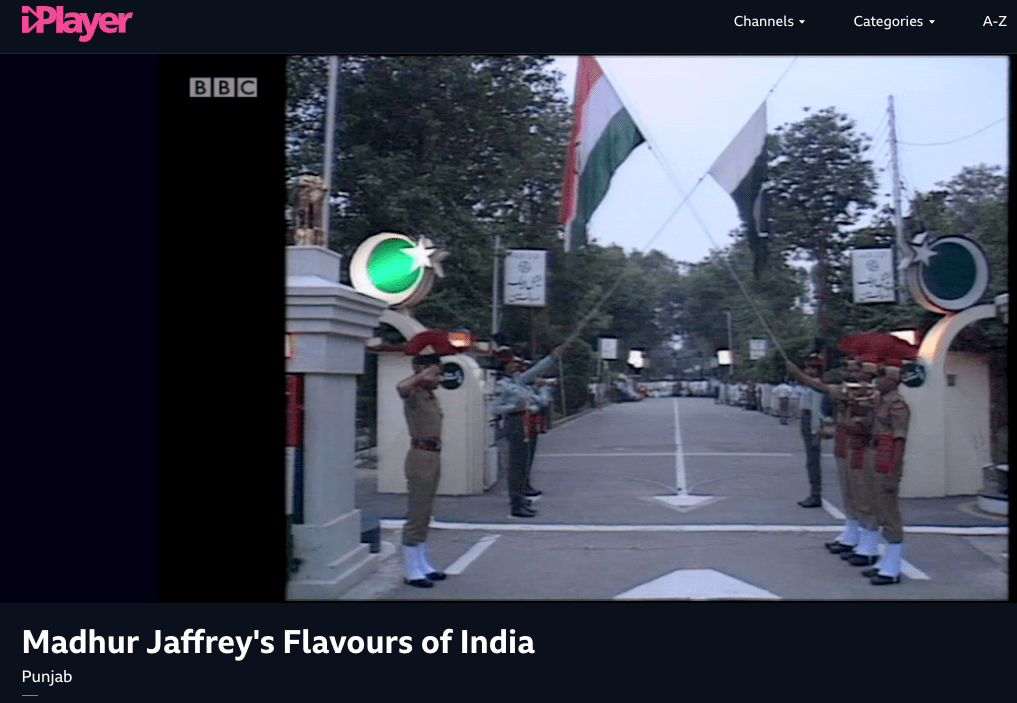

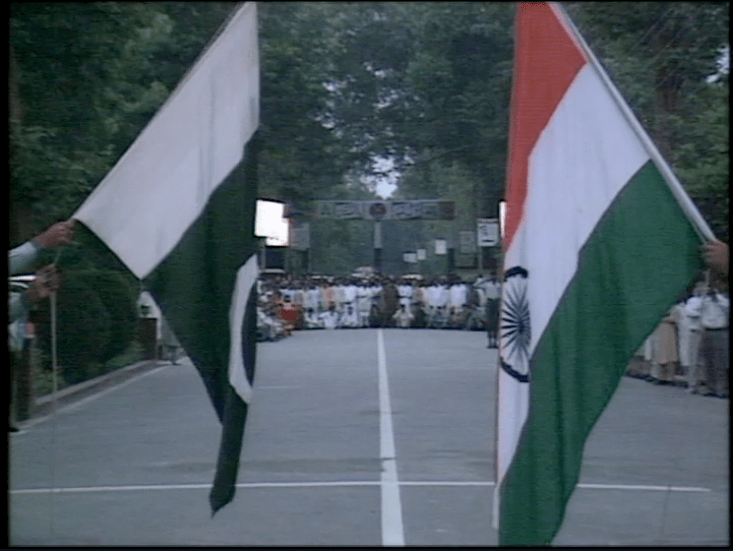

The villages of Ganda Singh Wala and Hussainiwala are two villages divided by Cyril Radcliffe’s line. Rather counter-intuitively in these times of Hindu/Sikh India and Muslim Pakistan, Ganda Singh Wala is a village in Kasur District in Punjab, Pakistan, while Hussainiwala is its Indian counterpart, located 11 km away from Ferozepur city. Until the early 1970s, this was the primary border crossing between the two countries but it now only functions as a ceremonial border. Like Wagha-Attari, the now-primary border crossing between India and Pakistan, there is a daily Retreat Ceremony with the lowering of the national flag. There are, however, a few differences between the two ceremonies as Ganda Singh-Hussainiwala is generally not open to foreign tourists and is therefore more intimate with fewer attendees coming largely from the local area. The seating, especially on Ganda Singh side, is right next to the Pakistani Rangers and thus provides a spectacular viewing of this daily spectacle.

While restricted to mostly locals, there remains some jingoistic overtures around it; more palpable during tense times between the two countries. The ceremony lasting 40 minutes, is shorter than the Wagha-Attari version and has less of a fanfare and build-up. People loiter around, catching the opportunity to be close to Indian/Pakistani people and take photos of the Rangers and Indian BSF. According to Ferozepur district’s webpage (http://ferozepur.nic.in/html/indopakborder.html), there was no joint parade and retreat ceremony here until 1970. It was apparently, “Inspector General BSF, Ashwani Kumar Sharma, called upon both authorities to have joint retreat ceremony and since than it has become a tradition”. In 2005, there were discussions about opening this border crossing, to no avail. Today it is easy to forget that this was once a thriving check-point. In 1970, Paul Mason, while travelling the sub-continent, excitedly crossed the border from Ganda Singh to Hussainiwala. He recalls this experience in his travelogue, Via Rishikesh: an account of hitchhiking to India in 1970 (2005):

“In the morning we have little difficulty in locating the Ministry of the Interior and are supplied the necessary chits which give permission for us to travel along the restricted road to the border. For the sum of two rupees apiece we obtain bus seats and are soon headed off down the dusty track, but the trip is much longer than I expect and it is mid-afternoon before we arrive at the Pakistani customs of Ganda Singh Wala.

At the customs post on the Indian side of the border, a worryingly intelligent young woman who reminds me much of my elder sister Margaret deals me with. I do my best to conceal my anxiety about the concealed roll of banknotes. She eyes me carefully and exchanges a few words with me before turning to the next in line without first acquainting herself with the contents of my underpants.

We have made it to India! We are here in India! At last! Amazing, amazing, amazing!

I take a look at stamp in my passport; it states simply; ‘ENTRY 16-10-70 Hussainiwala Distt, Ferozepore’ – not even a mention of India! Oh well, we’re here, and that’s all that counts!

We follow the flow of other new arrivals along a path beside a wide still river [Sutlej]. There is also a disused railway track, which presumably used to connect the two countries.”

[See full account: http://www.paulmason.info/viarishikesh/viarishikeshch16.htm]

We see from Mason’s account of the simplicity through which he crossed the border with only a slight mention of Ganda Singh and Hussainiwala printed in his passport (pictures of the entry stamps are available on his website above). Today when crossing via the land route, there is a clear stamp with Attari (India) and Wagha (Lahore) in the passport. Mason also mentions the hundreds of cars left abandoned at the border because it was too costly to take them across. But, this was at least possible to do then; impossible today. Equally, the disused railway track lies there abandoned but remains as a reminder of the two broken halves.

Ferozepur, India is the land of martyrs and Hussainiwala is the site of the National Martyrs Memorial, where Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru were cremated on 23 March 1931. This is also the cremation place of Batukeshwar Dutt, who was also involved in bombing the Central Legislative Assembly with Singh. Bhagat Singh’s mother, Vidyawati, was also cremated here according to her last wishes. Interestingly, the spot of the memorial, which is only 1 km away from Hussainiwala and on the banks of the Sutlej river and built in 1968, was originally part of Pakistan. On 17 January 1961, it was returned to India in exchange for 12 villages near Sulemanki Headworks.

Read ‘Making of a Memorial’ by K. S. Bains, http://www.tribuneindia.com/2007/20070923/spectrum/main2.htm

-, ‘Shaheedon ki dharti’ in The Tribune: http://www.tribuneindia.com/1999/99jul03/saturday/regional.htm#3

See a short clip of the ceremony at Ganda Singh Wala: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vZR-eLVYo6s

From before and beyond the international border that divides them, there is a story that connects these villages. Majid Sheikh writes about the ‘Spiritual connect of two villages’ in Dawn and brings out their historic connections. To commemorate a highly decorated soldier, Risaldar Major Ganda Singh Dutt, the British had named this village after him, while the village Hussainiwala derived its name during colonial days from Pir Ghulam Husseini, whose tomb is now in the BSF headquarters. Today they exist as two halves of the same story.

Read ‘Spiritual connect of two villages on both sides of the divide’ by Majid Sheikh: https://www.dawn.com/news/1379906