Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (born April 14, 1891, Mhow, India—died December 6, 1956, New Delhi), leader of the Dalits (Scheduled Castes; formerly untouchables), chairman of the drafting committee of the Constituent Assembly of India (1946-49) and law minister of the government of India (1947-51).

On his 131st birth anniversary, I share below an excerpt from a paper read by a 25-year-old Ambedkar titled Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis, and Development, at Columbia University, New York, U.S.A. on 9 May 1916:

Subtler minds and abler pens than mine have been brought to the task of unravelling the mysteries of Caste ; but unfortunately it still remains in the domain of the “unexplained”, not to say of the “un-understood” I am quite alive to the complex intricacies of a hoary institution like Caste, but I am not so pessimistic as to relegate it to the region of the unknowable, for I believe it can be known. The caste problem is a vast one, both theoretically and practically. Practically, it is an institution that portends tremendous consequences. It is a local problem, but one capable of much wider mischief, for “as long as caste in India does exist, Hindus will hardly intermarry or have any social intercourse with outsiders; and if Hindus migrate to other regions on earth, Indian castes would become a world problem.”

Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 1, pp. 5-6

And pasted below are a slice of the meagre UK newspaper reportage across the first three decades after Ambedkar’s death, when he was not the indispensable icon that he has become in the India since 1990-91:

“Dr Ambedkar”, ‘…had once thought of asking to be received as a Sikh’ – political rather than theological conversion to Buddhism, therefore – opinion is equally divided on whether Untouchability is dying out or whether the caste system is still rigid, though it may take rather new forms’ – ‘the Untouchables would be happier if, without exaggerating their separateness from the main body of Hindus, they can produce more leaders to carry on Ambedkar’s work’.

7 December 1956, The Manchester Guardian, p. 10

“India’s former Untouchables seek arrest” – ‘Harijans all over India have launched an agitation to press their demands…yesterday 500 demonstrators courted arrest…but the Harijans lack the political organisation or the strength within society to raise anything more than a matter of discontent, easily ignored…the Harijan agitation is being directed by the RPI, the descendent of the old SCF, which the late Dr Ambedkar made a political force in the years before independence but which has shrunk in influence [since]…the agitation was launched on Dr Ambedkar’s birthday yesterday in support of a charter of 10 demands placed before the PM two months ago (land, houses, fair distribution of food grains, enforcement of the laws against untouchability and “immediate cessation of harassment” of Harijans)…the Harijans are stirring…stiffening through desperation or anger [as evidenced] by clashes between caste Hindus and “neo-Buddhists” (Harijans who have converted to Buddhism) in Maharashtra’.

8 December 1964, The Times, p. 9

“The timeless untouchable Indian problem” – ‘not a small minority: 20% in UP, WB, Haryana, Punjab; 10% in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Kerala, and Assam… ‘what has happened to [them] in these past 30 years? Very little, according to Mr. Dilip Hiro, The Untouchables of India. [On] the Untouchability (Offences) Act, 1955, ‘if we took this law seriously, said one state police chief, half the population in the state would have to be arrested’. [Reservation] ‘has tended to break up or drain off any kind of movement fighting for untouchable rights…Dr Ambedkar, the first Untouchable leader, believed that their status would be ameliorated only when the caste system itself was ended in India and there are no signs at all of that. Among western anthropologists, this…may be seen as an effective and defensible ordering of society. Nor does it seem likely that Mrs. Gandhi’s new order, powered by the authority of Kashmiri Brahmins, is going to start at the bottom of the Indian social heap’.

23 February 1976, The Times, p. 6

“14 killed as caste violence strikes at Bihar village” – ‘the third serious outbreak of caste violence [against Harijans by middle-ranking caste Hindus] in northern India in just over one month’ – ‘during the Janata rule in Bihar, the middle-ranking so-called “backward” castes seized the advantage over the former upper castes’ – ‘atrocities had increased recently against Harijans and other economically weaker groups…because other communities had become jealous of their advance, according to Mrs. Savita Ambedkar, widow of Mr. B.R. Ambedkar, the prominent Harijan leader who helped to draft the Indian constitution’.

27 February 1980, The Times, p. 9

Postscript:

On 7 August 1990, Vishwanath Pratap Singh, the prime minister at the time, announced that Other Backward Classes (OBCs) would get 27 per cent reservation in jobs in central government services and public sector units. The announcement was made before both Houses of Parliament. The decision was based on a report submitted on 31 December 1980 that recommended reservations for OBCs not just in government jobs but also central education institutions. The recommendation was made by the Mandal Commission, which was set up in 1979 under the Morarji Desai government and chaired by B.P. Mandal (former chief minister of Bihar). 30 years since Mandal Commission recommendations — how it began and its impact today by Revathi Krishnan 7 August 2020, The Print.

Read more:

Educate, Agitate, Organise – a short biography of Dr B R Ambedkar by Sonali Campion, 26 April 2016.

Mr. Gandhi and the Emancipation of the Untouchables by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar.

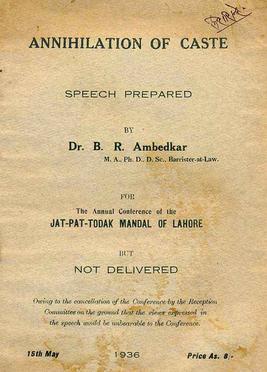

The Annihilation of Caste by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji.