Extracts taken from the Democracy Report 2021:

Electoral autocracies continue to be the most common regime type. A major change is that India – formerly the world’s largest democracy with 1.37 billion inhabitants – turned into an electoral autocracy. With this, electoral and closed autocracies are home to 68% of the world’s population. Liberal democracies diminished from 41 countries in 2010 to 32 in 2020, with a population share of only 14%. Electoral democracies account for 60 nations and the remaining 19% of the population. (p13)

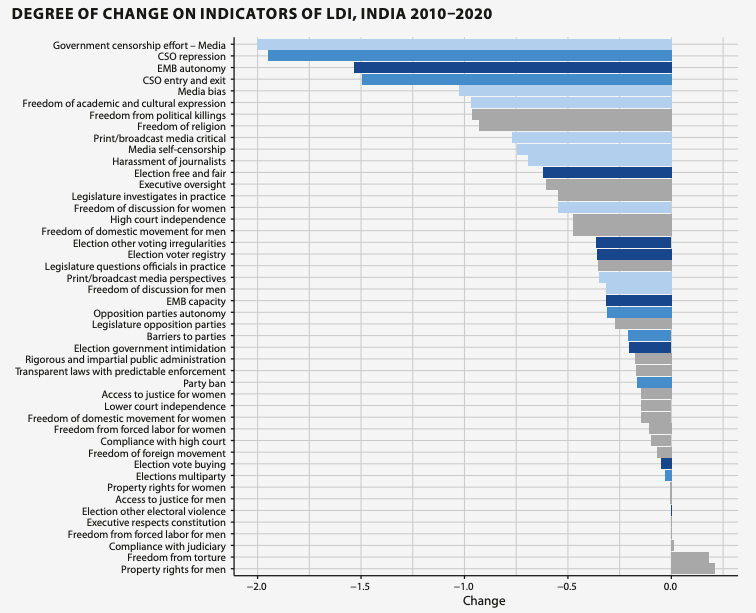

Yet, the diminishing of freedom of expression, the media, and civil society have gone the furthest. The Indian government rarely, if ever, used to exercise censorship as evidenced by its score of 3.5 out of 4 before Modi became Prime Minister. By 2020, this score is close to 1.5 meaning that censorship efforts are becoming routine and no longer even restricted to sensitive (to the government) issues. India is, in this aspect, now as autocratic as is Pakistan, and worse than both its neighbors Bangladesh and Nepal. In general, the Modi-led government in India has used laws on sedition, defamation, and counterterrorism to silence critics.1 For example, over 7,000 people have been charged with sedition after the BJP assumed power and most of the accused are critics of the ruling party. (p20)

Recently, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) from 1967 and amended in August 2019 is being used to harass, intimidate, and imprison political opponents, as well as people mobilizing to protest government policies.6 The UAPA has been used also to silence dissent in academia. Universities and authorities have also punished students and activists in universities engaging in protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). (p20)

Democracy Report 2021 by V-Dem Institute

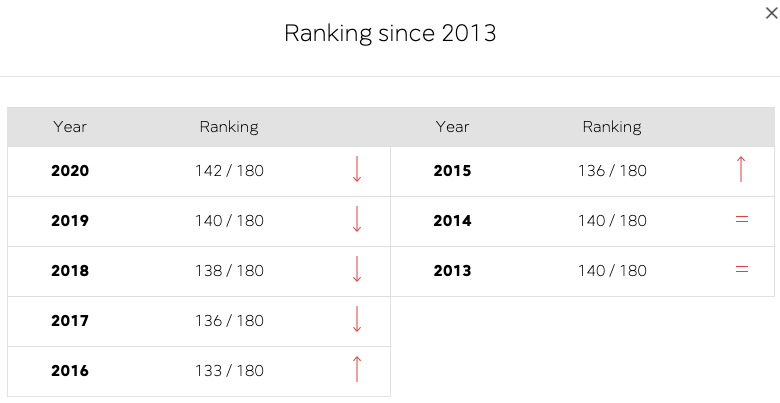

India has consistently been ranked amongst the lowest countries in the annual reports by Reporters without Borders in Press Freedom Index:

Read Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, ‘India complains about low press freedom rank – even as ministers talk of ‘neutralising’ journalists’ Scroll, 28 Mar 2021

Read the piece by Atikh Rashid on “What are democracy and autocracy waves? What’s behind the surge of autocratisation across the world?” Man Bites Dog, 18 Mar 2021

In my own piece written to coincide with 70 years of independence for India and Pakistan, I wrote the following:

Protests at Jawaharlal Nehru University in 2016 and Ramjas College at Delhi University in 2017, with chants of Azaadi (freedom), clearly showed that the idea of freedom is not merely an act of political freedom and is certainly not a freedom from thought in the increasingly mind-numbing and stealth homogenization of the millennial generation. It entails actual and real freedoms, freedoms which allow citizens to exist without fear of persecution, fear of raising critical voices, fear of consumption and cultural practices, fear from oppression and, above all, freedom from having a question mark at their very existence just for being.

The role of any democratic country, with a well-defined rule of law, is to protect all its citizens, ensuring that their rights and freedoms are safeguarded. This is especially true of countries where, as in the case of Pakistan, there is a significant minority; and in the case of India, though a majority Hindu state, secularism is enshrined in its constitution. It is in fact difficult to imagine these lands without the heterogeneity that forms the essence of being South Asian. It is this vibrancy and diversity that gives it character and strength. To move toward a homogenous culture is not only problematic but also dangerous because it is based on exclusivity.

Freedom and Fear: India and Pakistan at 70