When we visualise India’s Partition of 1947, we almost always do so through the images of Margaret Bourke-White. For the past seven decades, her images have saturated the cover of numerous books, newspaper articles, magazine features, documentaries et al related to Partition. She was, of course, one of the most iconic photographers of the last century. Born in 1904 (d. 1971) in New York City and raised in rural New Jersey, she was the daughter of Joseph White (who was of Jewish descent from Poland) and Minnie Bourke, an Irish Orthodox Catholic. Joseph was an inventor and engineer and perhaps thus an early influence on his daughter’s eventual interest.

This interest matched the tenor of those times, as Henry R Luce, the publisher tycoon realising the potential of photography, felt that America was ready for a magazine that documented events the through photographs. In 1936, Luce bought Life magazine and relaunched it, with Bourke-White becoming one of the first photojournalist to be offered a berth there (Kapoor: 13). America then was in the midst of the Great Depression and Bourke-White ‘took to documentary photography in order to disseminate the idea of inconvenient truth’ for a readership of 2.86 million people (Bhullar: 301).

In India, she is primarily known for her photographs that captured the Partition-related violence and migration, as it ushered in the new dawn of independence. Her photographic essay, The Great Migration: Five Million Indians Flee for Their Lives, was published in Life magazine on 3 November 1947. It had commissioned her to cover the exchange of populations that was taking place across the plains of the divided Punjab and she writes thus what she saw: “All roads between India and Pakistan were choked with streams of refugees. In scenes reminiscent of the Biblical times, hordes of displaced people trudged across the newly created borders to an uncertain future” (Kapoor: 14).

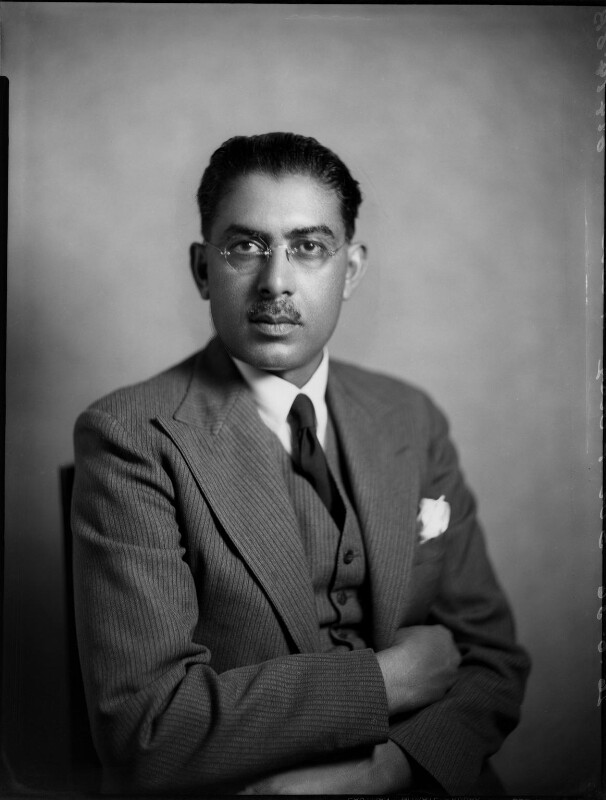

Recently, in 2010, Pramod Kapoor published Witness to life and freedom: Margaret Bourke-White in India & Pakistan with a reprint of over 100 of her photographs. Kapoor wrote about them thus: “They offer a kind of stately, classical view of misery, of humanity at its most wretched, yet somehow noble, somehow beautiful”. His book gives us into a glimpse beyond the frames. Bourke-White had arrived in India in March 1946 and travel around documenting low life and high people: “She was there to photograph Gandhi at his spinning wheel. She was there to photograph Jinnah with his fez. And soon after, both men were to meet their Maker” (Kapoor: 14). Her frames on them served to reinforce their pervading stereotypes of the saint and shrewd. Kapoor details:

“Margaret photographed Gandhi many times afterward. He called her, fondly, she thought, ‘the torturer’. His inconsistencies puzzled her rational mind; it was not until she saw his self-sacrificing bravely in the face of India’s convulsive violence that she began to think him akin to the saint she made him out to be with her camera. She also photographed Mohammed Ali Jinnah; whose features were as sharp as the creases in his western business suits. Jinnah would almost single-handedly bring about the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan”.

Bourke-White documented the aftermath of the so-called Direct-Action Day in August 1946, which was announced by Jinnah following the failure of the Cabinet Mission Plan. Her photographs of the riots in Calcutta then are sometimes confused with the images she took following the Partition, a year later. The article ‘The Vultures of Calcutta’ featured in the 9 September 1946 issue of Life, showing vultures waiting to prey on the bodies of dead victims was later, intermittently and inaccurately, used for depicting the carnage in August 1947.

Vicki Goldberg, the biographer of Bourke-White, writes that when she heard about the Calcutta Riots, Bourke-White immediately flew to Calcutta, and “badgered photographer Max Desfor (1913-2018), the first foreigner to photograph the aftermath of the riots, to tell her where to find the most carnage. While others were sickened by the sight of the bodies, Bourke-White kept working and wrote the scene reminded her of concentration camps in Germany: “the ultimate result of racial and religious prejudice” (Forbes: 7). Desfor’s images were not published by the Associated Press because they were “too revolting for its readers”. Bourke-White’s comrade was Lee Eitingon, a Life reporter based in India, in whose words, “Both of us were whatever the female equivalent of macho is. The smells were so terrible, the officers accompanying us would have handkerchiefs over their faces. We would not…that was part of the time and the period. Being women, we had to be tougher” (Kapoor: 27).

Much of Bourke-White’s archive are housed in Syracuse University’s Bird Library Special Collections section. Here “one can find some of the original photos that include the British soldiers who accompanied Bourke-White and Lee Eitingon” but, as Forbes notes, “the soldiers were cropped from the published pictures”, which dramatically changes the visual narrative (12). It now appears that Bourke-White staged photographs: “Eitingon wrote about her directing a group of starving Sikh refugees…to go back again and again”. She adds, “they were too frightened to say no. They were dying”. When Eitingon protested, Bourke-White told her “to give them money!” (Forbes: 11-12). Even Patrick French writes about how some of these images were staged. When the contact sheets were discovered, they provided an insight into the wider context in which these photographs were being taken. Some of this approach of a pushy, zealous and ambitious American, has been noted in the writing of Claude Cookman. In his examination of how Bourke-White and her French counterpart Henry Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) approached the coverage of Gandhi’s funeral he notes:

“Flash had become a contentious issue in Bourke-White’s coverage of Gandhi. She had used a flash bulb to make her famous portrait of Gandhi by his spinning wheel. Gandhi…tolerated the technique, but his inner circle never did. They thought flash was disrespectful, and they feared the bright light would harm his sensitive eyes. Flash became a serious liability for Bourke-White in her coverage of Gandhi’s funeral. With her camera concealed, she slipped into the room, where his body lay surrounded by grieving relatives, supporters and government officials. It was about 6:30 p.m.…When she ignited a flash bulb to make her exposure, his followers became enraged by her violation of their privacy and grief. They seized her camera and threatened to destroy it. Hannah Sen intervened, calming the group. After Bourke-White’s film was removed and exposed to the light, Mrs. Sen escorted her from the room. She returned the camera with the understanding that Bourke-White would leave Birla House and not return. Not one to give up after one rebuff, she reloaded her camera and tried to re-enter the room to get another picture. Eventually, Bourke-White yielded to Mrs. Sen’s pleas to honour her promise and left empty-handed. The stereotype of the rude, aggressive American news photographer, who would trample on anybody’s toes or sensitivities to get the picture was a commonplace during the 1940s…Cartier-Bresson deplored this rough-and-tumble approach to photo-journalism: ‘We are bound to arrive as intruders’, he wrote, ‘it is essential, therefore, to approach the subject on tiptoe. It’s no good jostling or elbowing’. As part of his approach, he rejected artificial lighting: ‘And no photographs taken with the aid of flashlight either, if only out of respect…Unless a photographer observes such conditions as these, he may become an intolerably aggressive character’. When Cartier-Bresson wrote this rejection of flash in 1952, he may well have been recalling Bourke-White’s experience at Gandhi’s wake four years earlier” (Cookman: 200).

Geraldine Forbes also notes the differences between Cartier-Bresson and Bourke-White. The former is less known but his images exude a sensitivity, absent in the work of Bourke-White. Upon receiving a photography award, Bourke-White claimed, “The photographer must know. It is his sacred duty to look on two sides of a question and find the truth”. And she cited her work to reference this point (Kapoor: 26). However, when we look at her work, we rarely observe that her work, almost entirely based on the Punjab migration, has yet been made to stand for Independence/Partition exclusively, without acknowledging the vast and diverse range of experiences. The visual record which is taken as “the truth” is rarely explored critically or contextually, while less said so of the racial-ethnic cultural capital of a white American female to travel freely to photograph this momentous carnage at the end of empire. These were foreign journalists writing for a predominately American and western audience, yet these photographs have come to represent Partition.

References:

Dilpreet Bhullar, ‘The Partition of the Indian Subcontinent Seen through Margaret Bourke-White’s Photographic Essay: ‘The Great Migration: Five Million Indians Flee for their Lives’, Indian Journal of Human Development, (2012) 6 (2): 299-307.

Claude Cookman, ‘Margaret Bourke-White and Henri Cartier-Bresson: Gandhi’s funeral’, History of Photography 22, no. 2 (1998): 199-209.

Geraldine Forbes, ‘Margaret Bourke-White: Partition for Western Consumption’, In Reappraising the Partition of India edited by K. Mitra and S. Gangopadhyay (Readers Service, 2019), pp. 3-16.

Patrick French, ‘A New Way of Seeing Indian Independence and the Brutal ‘Great Migration’, Time, 14 August 2016.

Vicki Goldberg, A Biography. New York: Harper & Row. 1986.

Pramod Kapoor, Witness to Life and Freedom: Margaret Bourke-White in India & Pakistan. New Delhi: Roli & Janssen. 2010.

Asma Naeem, ‘Partition and the Mobilities of Margaret Bourke-White and Zarina’, American Art 31, no. 2 (2017): 81-88.

Pramod K. Nayar, ‘The Trailblazing Lens of Photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White’, The Wire, 28 Sept 2019.

Bio/profile/work:

Alan Taylor, ‘The Photography of Margaret Bourke-White’, The Atlantic, 28 August 2019.

The Pioneering Photography of Margaret Bourke-White by Google Arts & Culture