Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (14 April 1891 – 6 December 1956)

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji, and Frances W. Pritchett. Pakistan or Partition of India. Thacker, 1946

The Muslim League’s Resolution on Pakistan has called forth different reactions. There are some who look upon it as a case of political measles to which a people in the infancy of their conscious unity and power are very liable. Others have taken it as a permanent frame of the Muslim mind and not merely a passing phase and have in consequence been greatly perturbed.The question is undoubtedly controversial. The issue is vital and there is no argument which has not been used in the controversy by one side to silence the other. Some argue that this demand for partitioning India into two political entities under separate national states staggers their imagination; others are so choked with a sense of righteous indignation at this wanton attempt to break the unity of a country, which, it is claimed, has stood as one for centuries, that their rage prevents them from giving expression to their thoughts. Others think that it need not be taken seriously. They treat it as a trifle and try to destroy it by shooting into it similes and metaphors. “You don’t cut your head to cure your headache,” “you don’t cut a baby into two because two women are engaged in fighting out a claim as to who its mother is,” are some of the analogies which are used to prove the absurdity of Pakistan. In a controversy carried on the plane of pure sentiment, there is nothing surprising if a dispassionate student finds more stupefaction and less understanding, more heat and less light, more ridicule and less seriousness. My position in this behalf is definite, if not singular. I do not think the demand for Pakistan is the result of mere political distemper, which will pass away with the efflux of time. As I read the situation, it seems to me that it is a characteristic in the biological sense of the term, which the Muslim body politic has developed in the same manner as an organism develops a characteristic. Whether it will survive or not, in the process of natural selection, must depend upon the forces that may become operative in the struggle for existence between Hindus and Musalmans. I am not staggered by Pakistan; I am not indignant about it; nor do I believe that it can be smashed by shooting into it similes and metaphors. Those who believe in shooting it by similes should remember that nonsense does not cease to be nonsense because it is put in rhyme, and that a metaphor is no argument though it be sometimes the gunpowder to drive one home and imbed it in memory. I believe that it would be neither wise nor possible to reject summarily a scheme if it has behind it the sentiment, if not the passionate support, of 90 p.c. Muslims of India. I have no doubt that the only proper attitude to Pakistan is to study it in all its aspects, to understand its implications and to form an intelligent judgement about it.

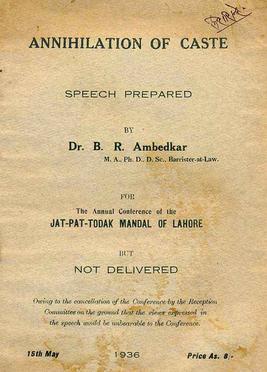

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Annihilation of Caste: The annotated critical edition. Verso Books, 2014.

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Annihilation of Caste: The annotated critical edition. Verso Books, 2014.

The Annihilation of Caste was an undelivered speech written in 1936 and to be delivered at the Jat-Pat Todak Mandal (Society for the Abolition of Caste system). However, the organiser found elements within the speech objectionable and Ambedkar refused to censor his words.

Roy, Arundhati, B. R. Ambedkar, and S. Anand. Annihilation of Caste: The Annotated Critical Edition. (2014).

Other contemporary abominations like apartheid, racism, sexism, economic imperialism and religious fundamentalism have been politically and intellectually challenged at international forums. How is it that the practice of caste in India – one of the most brutal modes of hierarchical social organisation that human society has known – has managed to escape similar scrutiny and censure? Perhaps because it has come to be so fused with Hinduism, and by extension with so much that is seen to be kind and good – mysticism, spiritualism, non-violence, tolerance, vegetarianism, Gandhi, yoga, backpackers, the Beatles – that, at least to outsider, it seems impossible to pry it loose and try to understand it.

Listen to The Doctor and The Saint: The Ambedkar—Gandhi debate: Race, Caste and Colonialism with Arundhati Roy (2014)

O’Boyle, Jane “The New York Times and the Times of London on India Independence Leaders Gandhi and Ambedkar, 1920–1948” American Journalism, Volume 35, 2018 – Issue 2, 214-235.

During the years before India’s independence, the Times of London published news stories that were derisive and skeptical of Mahatma Gandhi, reflecting a national policy to diminish his power in the process to “quit India.” The Times was respectful of the untouchables’ leader Bhimrao Ambedkar and his civil rights movement for untouchables, perhaps to further distract from Gandhi’s popularity. The New York Times lavished positive attention on Gandhi and largely ignored Ambedkar altogether. The American newspaper framed a hero of colonial independence and never his oppression of untouchables, adhering to news policy during the Jim Crow era of racial persecution.

Teltumbde, Anand. The Persistence of Caste: The Khairlanji murders and India’s hidden apartheid. Zed, 2010.

While the caste system has been formally abolished under the Indian Constitution, according to official statistics, every eighteen minutes a crime is committed in India on a Dalit-untouchable. The Persistence of Caste uses the shocking case of Khairlanji, the brutal murder of four members of a Dalit family in 2006, to explode the myth that caste no longer matters. In this exposé, Anand Teltumbde locates the crime within the political economy of post-Independence India and across the global Indian diaspora. This book demonstrates how caste has shown amazing resilience – surviving feudalism, capitalist industrialization and a republican constitution – to still be alive and well today, despite all denial, under neoliberal globalization.

Teltumbde, Anand. “Deconstructing Ambedkar,” Economic and Political Weekly (May 2, 2015).

Electoral politics became competitive bringing to the fore vote blocks in the form of castes and communities, both skilfully preserved in the Constitution in the name of social justice and religious reforms, respectively. The competing Ambedkar icons offered by various political manufacturers in India’s electoral market have completely overshadowed the real Ambedkar and decimated the potential weaponry of Dalit emancipation. The rhetoric of aggressive development, modernity, open competition, free market, etc, necessitated the projection of a new icon which would assure people, particularly those of the lower strata whom it would hit most, of the possibility of a transition from rags to riches with the adoption of the free-market paradigm.

Further Reading

Ministry of External Affairs (GoI): Writings & Speeches of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar https://www.mea.gov.in/books-writings-of-ambedkar.htm

Jaffrelot, Christophe. India’s silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. Orient Blackswan, 2003.

Jodhka, Surinder S. “Caste: why does it still matter?.” In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India, pp. 259-271. Routledge, 2015.

Pandey, Gyanendra. A history of prejudice: race, caste, and difference in India and the United States. Cambridge University Press, 2013.